On 24th May 2021, the Central government issued a notification, enabling the feature for on-site registration and appointment on the CoWIN platform for the age group 18-44 years.[1] Prior to this, the Centre had only allowed for an online appointment mode for this age group when the vaccination coverage was extended to it on 1st May 2021. The order to open spot-registrations and the decision to not solely rely on Digital India machinery (CoWIN, Aarogya Setu, UMANG apps and Common Service Centres (CSC)) is the right move by the Centre. Earlier, in an affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court of India on 9th May 2021, the Centre had defended its COVID-19 inoculation policy and more specifically, its decision to employ a digitised interface to onboard vaccine beneficiaries. It had argued that citizens who cannot access CoWIN on their own, especially in the rural areas, can get assistance from Common Services Centres (CSC) established at the Gram Panchayat (GP) level across the country. In this post, notwithstanding the supply concerns, we discuss why moving away from the old digital-only strategy to the new one is an essential policy decision to successfully cover scores of the vulnerable population unable to use the previously mandated digital process.

CoWIN, a web portal that is currently facilitating vaccine registration, management of vaccine stocks, and session management (the linking of vaccination sites to beneficiaries), has attracted a fair amount of criticism. The key concern is the lack of accessibility to the portal for a large portion of the population unfamiliar with navigating digitised interfaces or simply lacking internet connectivity. While the CSC network can be an important channel to bolster vaccine registration in villages, the Centre’s previous policy not only begot questions around the actual capacity of the CSC infrastructure but also around some of the design issues within the model itself.

Some of our earlier work has attempted to analyse the suitability of the CSC network for the delivery of welfare and other G2C services in the last-mile, especially around the themes of incentive structures, lack of financial sustainability of the model, and accountability mechanisms. In this blog post, we attempt to unpack a crucial question, how effective could the CSC model of facilitating vaccine registration be?

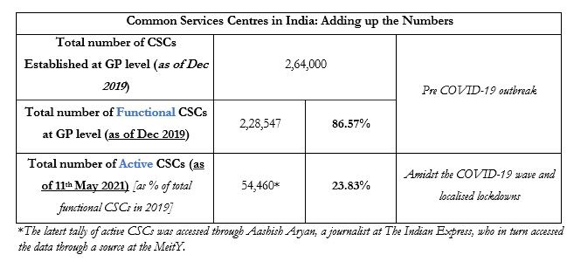

The most fundamental question is related to infrastructural adequacy – are there enough CSCs to assist India’s digitally excluded[2] access CoWIN? A 2019 Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) report to the Lok Sabha places the number of active CSCs at 3,65,000, of which 2,64,000 are at the GP level. Out of these, only 2,28,547 were reported as “functional” in December 2019. While it is difficult to tally the exact number of unserved GPs (due to paucity of accurate data), anywhere between 21,453 (a conservative estimate) to 37,875[3] (a liberal estimate) gram panchayats do not have a Common Service Centre.

Secondly, even if present, the erratic functioning of CSCs during COVID-19-induced lockdowns is a grave concern. According to the latest data from MeitY,[4] only 54,460 village-level entrepreneurs (VLEs, or CSC owners) were active as of 11th May 2021. This is only 23.83% of the total number of functional CSCs reported in 2019. The main reason for most CSCs being currently inactive is the lockdown/curfew situation across states, with most of them not recognising them as “essential services”.

Table 1: Number of CSCs in India

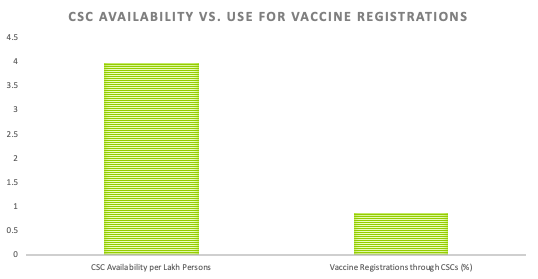

In addition to these accessibility issues, we also noticed a low uptake of the vaccine registration service itself at CSCs.[5] Figure 1 plots, for each Indian state, the number of active CSCs per 100,000 persons[6] against the percentage of vaccine registrations made through CSCs[7] (all age groups, 1-11th May). While one may hope that states with higher availability of CSCs per capita may exhibit higher rates of vaccine registration through CSCs, this does not seem to be the case. In fact, in most states, only 1.5% of all vaccines seem to have been registered for through CSCs. In Odisha and Sikkim, CSCs play a marginally better role in vaccine registrations, contributing to around 3% of total vaccines administered in each of the states. For the remaining, only 0.6% of vaccinations between 1-11th March (across all age groups) were seen to be registered for through CSCs.

Figure 1: National Comparison of CSC Availability and CSC Use for Vaccine Registrations

Figure 2: State-wise Availability of CSCs vs. CSC Use for Vaccine Registration

Thirdly, there is a host of logistical issues (such as time and travel costs to access CSCs) associated with this approach. At a time when inoculation seems to be the only way to control the pandemic, relying solely on CSCs for vaccine registration in rural areas may have cost us dearly.

While assistance-based models form an important bridge between the citizen and state machinery in the last-mile, they might prove insufficient for such a large-scale, high-frequency exercise. Note here that the CSC scheme has been designed to deliver digital services to rural areas via “private entrepreneurs”, seeking to fulfil the dual goal of service delivery and livelihood promotion. The success of the model, as per guidelines, depends on the VLE’s “entrepreneurial ability” and “social commitment”, making CSCs a private agent-led model, with minimum involvement of any level of government. With many VLEs reporting difficulty in breaking-even in the absence of capital subsidies from the government, is it prudent to depend on these private citizens to facilitate vaccine registration during a deadly pandemic? What we need is a robust state-led distribution system, and the government must not pass the buck to the private sphere for a public good as crucial as this vaccination.

While we welcome the new move to allow for on-site registration at government CVCs, we further recommend that other government/quasi-government agents in the last-mile must be allowed to enrol citizens for vaccines, thereby increasing the number of access points available to citizens. The government, as recommended by several public health experts, can also follow the model for vaccination set out in India’s successful Universal Immunisation Programme for childhood vaccinations. The UIP follows three modes, routine, campaign, and outreach, conducted largely by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs). Vaccination is an essential public good, as noted by the recent Supreme Court order, and at this point, one of the key national priorities. A nascent, app-led architecture cannot be seriously expected to rise to the occasion during the country’s hour of need.

[1] This feature has been enabled only for government-run COVID Vaccination Centers (CVCs) for now and the final decision to implement this feature has been left to the discretion of states/UTs.

[2] Digital exclusion refers to the barriers that one faces with regards to connectivity (non-ownership of smartphone/computer, network issues), digital skills (ability to navigate digital systems), and accessibility (services not catered to various languages/disabilities).

[3] According to the 2011 Census of India, there were 2,50,000 GPs. However, the latest tally from the Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, stands at 2,66,422 GPs. This is because the number and the definition of villages vary across government databases.

[4] The latest tally of active CSCs was accessed through Aashish Aryan, a journalist at The Indian Express, who in turn accessed the data through a source at the MeitY.

[5] Please note that the analysis of demand-side factors such as vaccination hesitancy across states is outside the scope of this piece.

[6] This indicator is calculated as a ratio of number of active VLEs in each state (as on 11th May) to the projected population estimates for 2021.

[7] This indicator is calculated by dividing the number of vaccine registrations through CSCs by the total number of vaccines administered to all age groups for the dates 1-11th May (data from CoWIN dashboard).

Cite this item

APA

Gupta, A., & Narayan, A. (2021, May). Moving to Offline and On-Spot CoWIN Registration: Away from the Not-so-Common Service Centres. Retrieved from Dvara Research Blog.

MLA

Gupta, Aarushi and Aishwarya Narayan. “Moving to Offline and On-Spot CoWIN Registration: Away from the Not-so-Common Service Centres.” May 2021. Dvara Research Blog.

Chicago

Gupta, Aarushi, and Aishwarya Narayan. 2021. “Moving to Offline and On-Spot CoWIN Registration: Away from the Not-so-Common Service Centres.” Dvara Research Blog. May.