In December 2020, it was announced that India’s vaccination effort would be facilitated through CoWIN, a digital platform. The platform acts as a “cloud-based IT solution for planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of Covid-19 vaccines in India”. CoWIN is the newest among a host of digital platforms for social protection and welfare. Before evaluating such a platform, it is important to comprehend the platform and the larger ecosystem it inhabits. This piece seeks to impart such an understanding to the reader.

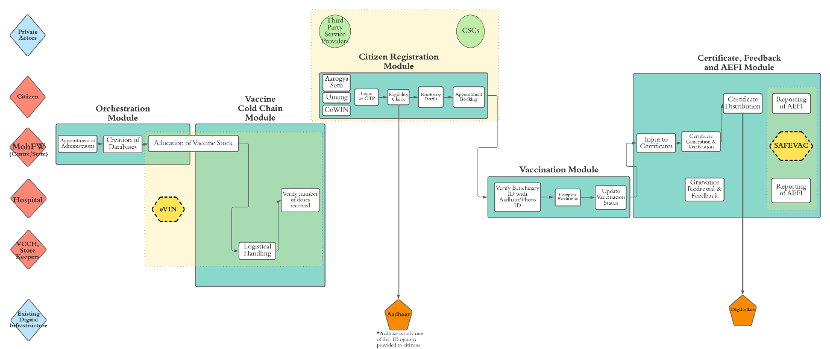

The CoWIN platform has been conceptualised to provide “end-to-end” support for the COVID-19 vaccination delivery system. CoWIN, which is managed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), was developed by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) on the Ministry’s behalf[1]. It accordingly plays multiple roles simultaneously through the vaccination delivery chain. The platform can assist in administrative management (through the Orchestration Module), monitor vaccine supply chains (Vaccine Cold Chain Module), onboard citizens as vaccine recipients (Citizen Module), and update their vaccination status (Vaccinator Module), and issue certificates after inoculation (Certificate, Feedback and AEFI Module).

Orchestration Module

The orchestration module creates administrators at the National, State and District Levels to be high-level coordinators: creating databases, allocating roles to other system users, managing inventory and tracking registered beneficiaries (through www.app.cowin.gov.in). The databases (or ‘registries’) are the primary information source for the platform (about beneficiaries, vaccination facilities, etc.) and permit modifications as required. Upon compilation of these databases, States devolve their vaccine stocks to districts, and districts to facilities. District Administrators can acknowledge the receipt of vaccine stocks through the CoWIN application.

Figure 1: Orchestration Module

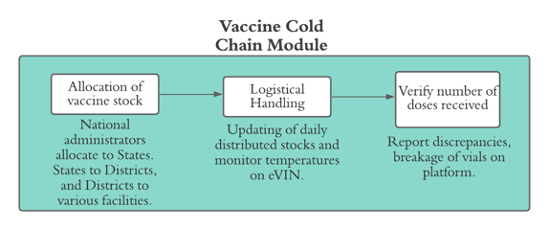

Vaccine Cold Chain Module

The vaccine cold chain module supports the procurement and supply chain logistics for vaccine stocks with a repurposed version of an existing web-based vaccine management system, eVIN (or Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network)[2]. The tool digitises COVID-19 vaccination stock and permits the real-time, remote monitoring of storage temperatures by vaccine and cold chain handlers through a mobile application and works in tandem with the citizen registration module. The app also allows for logging the status of daily vaccine distribution (at National, State, District, and regional cold storage levels), as well as the documentation of receipt of faulty stock.

Figure 2: Vaccine Cold Chain Module

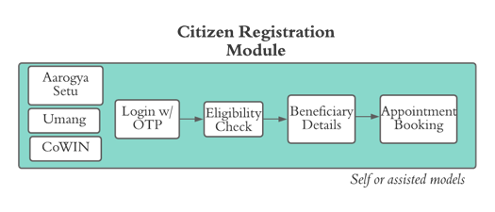

Citizen Registration Module

The citizen registration module of CoWIN permits citizens to enrol themselves as vaccine beneficiaries through one of the following access points: the www.cowin.gov.in website, the Aarogya Setu application, or the UMANG[3] application. Citizens select their preferred date, location, and vaccine program of choice, and may register four additional members for vaccination.

Figure 3: Citizen Registration Module

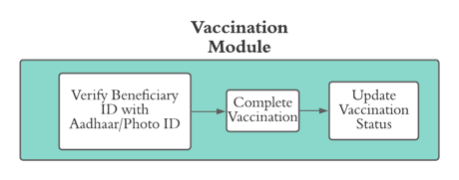

Vaccinator Module

This module is operated by vaccination officers to verify citizen identity and update citizens’ vaccination status at the session site. Upon status update, an SMS notification is sent to the citizen confirming their vaccination and providing a link and time for subsequent dosage. Supervisors at the site may also access this module to monitor and supervise the progress of vaccination sessions.

Figure 4: Vaccination Module

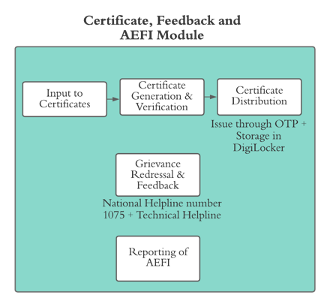

Certificate, Feedback and AEFI Module

The final module of CoWIN provides a second layer of ex-post interaction between the citizen and vaccine administrator for three purposes: issue of vaccine certificate, collection and management of feedback and grievances, and finally, the reporting of relevant aftereffects of immunisation (AEFI).

The Certification module, built on an open-source solution (DIVOC[4]), facilitates the generation of a vaccination certificate with the individuals’ personal particulars, distribution through an OTP based link, digital storage of the same through DigiLocker, and finally, verification through a QR code. It also permits citizens to correct any errors that may have permeated their certificates. The vaccination credentialing module of DIVOC was integrated into CoWIN with support from its creators at the e-Gov Foundation.

For grievance management, the MoHFW has established multiple helplines (for citizen grievances and CoWIN software-related issues). Grievances are reviewed by task forces at the Block, Urban, District and State levels. In March 2021, the UNDP (the leading development partner of CoWIN) published a Request for Proposals (RFP) to engage partners to aid in setting up a grievance management system.

Finally, the AEFI management for CoWIN is undertaken through integration of the SAFEVAC software into the CoWIN ecosystem. Citizens may use the registration module to self-report AEFI cases. Alternatively, the vaccination officer or district immunisation officer can report adverse events through the CoWIN app. This data is automatically transferred to the CoWIN-SAFEVAC system. Alternatively, there are offline mechanisms for AEFI reporting through primary health centres, auxiliary nurse midwives, etc.

Figure 5: Certificate, Feedback and AEFI Module

The CoWIN ecosystem is broader than just the above modules. It has been designed using public digital infrastructure and has fostered innovation to enhance it. CoWIN’s digital credentialing module is based on the open-source software of DIVOC. It has built upon Aadhaar[5] and Digilocker to integrate identity verification and certificate storage within the system. Pre-existing digital solutions such as eVIN and SAFEVAC allowed the quick deployment of information management systems to handle various aspects of the vaccine delivery chain with some modifications.

Further, the CoWIN system is built to enable various stakeholders to participate in it. For instance, State/UT governments or private service providers may develop software solutions compatible with CoWIN by accessing related data and utilising APIs[6]. Another stakeholder has been the Common Services Centres (CSCs)[7], which have been enlisted for agent-based vaccine registration of the digitally excluded.

Figure 6 compiles each of the components of CoWIN together to present a comprehensive picture of the entire ecosystem in terms of operational processes, actors, builders, and digital infrastructure.

Figure 6: The CoWIN Ecosystem

Since CoWIN is primarily a digital platform that collects citizen data, concerns have been raised regarding its data management policy. The platform collects data on name and gender (to verify eligibility) and mobile number and photo ID proof (to verify identity). The platform did not have an explicit privacy policy until about five months into operation. The platform’s privacy policy came on the heels of the Delhi High Court’s Orders, instructing the platform to have an independent privacy policy. This privacy policy is set along the main data protection principles such as use limitation, purpose specification, data retention, etc. However, there remains significant ambiguity around key questions of data protection such as (i) the location at which the personal data will be stored, (ii) the government agencies at the state and central level that can access the data, (iii) if the personal data will be encrypted, (iv) the rationale for not having a time-bound data retention policy. In addition to these questions on data protection, significant concerns also persist on the ease of accessibility of the privacy policy. On the day of the rollout, the privacy policy was only available in English. It is now unclear how it will be made compatible with the KaiOS interface and the telephonic helpline (1075). Furthermore, the creation of a Unique Digital Health ID[8], as suggested by health secretary Rajesh Bhushan, raises some questions with respect to data protection.

CoWIN is a fascinating example of a digital platform within a larger ecosystem of multiple actors, digital solutions, and governance policies. As we have cautioned in our earlier work, digital systems that deliver welfare services must be preceded by a pivot to exclusion-reduction. Unless such systems are actively designed with the end-user in mind, they are bound to face considerable obstacles. In the ecosystem approach, the citizen-centricity required is magnified to each aspect and player encompassed within. As India adopts open digital ecosystems in more fields, the principles of inclusiveness, responsibility and accountability will have to become as important as efficiency.

[1] Media reports suggest that the UNDP outsourced creation of the platform to a private software provider, Trigyn Technologies.

[2] eVIN is a tool that enables data-driven management of vaccination supply stock. It has been developed in partnership with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and has been in use since 2017. eVIN has supported multiple immunization efforts targeted at women and children.

[3] The Unified Application for New-age Governance (UMANG) is a mobile application that acts as an aggregator platform for multiple Central and State G2C services.

[4] DIVOC is an open-source digital platform built to orchestrate large scale digital vaccination and certification programs and is an integral part of India’s CoWIN platform. It envisions itself as a digital public good catering to various users (national level governments, or even private organisations), and tailorable in a plug and play manner with various existing ID and payments systems. DIVOC has been developed by the eGov Foundation as a part of ‘DIGIT’, a stack of APIs and services that allow ecosystem players to build solutions at a large scale for urban India.

[5] The CoWIN ecosystem does accept a list of non-Aadhaar IDs.

[6] Many private individuals have built services as part of the CoWIN ecosystem: to notify citizens of registration opportunities. The most recent guidelines even permit third-party apps to directly register and schedule appointments or manage COVID-19 vaccination and facilities, through protected APIs.

[7] CSCs are internet-enabled front-end delivery points for a range of G2C and B2C services across India. They are set up in a PPP-mode, are primarily located in rural parts of the country and are run by private citizens referred to as ‘Village Level Entrepreneurs’ (VLEs).

[8] The digital health ID is a 14-digit number which will be issued to each Indian under the National Data Health Mission and will permit the creation of longitudinal health records for all individuals.

Cite this item

APA

Narayan, A., & Narang, L. (2021). The Actors and Operations of a Digital Delivery Platform: CoWIN. Retrieved from Dvara Research Blog.

Chicago

Narayan, Aishwarya, and Lakshay Narang. 2021. “The Actors and Operations of a Digital Delivery Platform: CoWIN.” Dvara Research Blog.

MLA

Narayan, Aishwarya and Lakshay Narang. “The Actors and Operations of a Digital Delivery Platform: CoWIN.” 2021. Dvara Research Blog.