In our earlier post in this series, we noted that India tends to take a narrow, scheme-based approach to welfare. This is problematic for a number of reasons, most prominently, that schemes are made by executive order rather than by statute and often without an effective enforcement mechanism.

By and large, the present Budget continues with the schemes announced in 2019-20. Further, more pressing concerns arise with respect to the lower allocations for many crucial welfare schemes, as well as the low spending by the government on social welfare in 2019-20. In this post, we highlight some concerns with the allocations for social welfare in the budget for 2020-21.

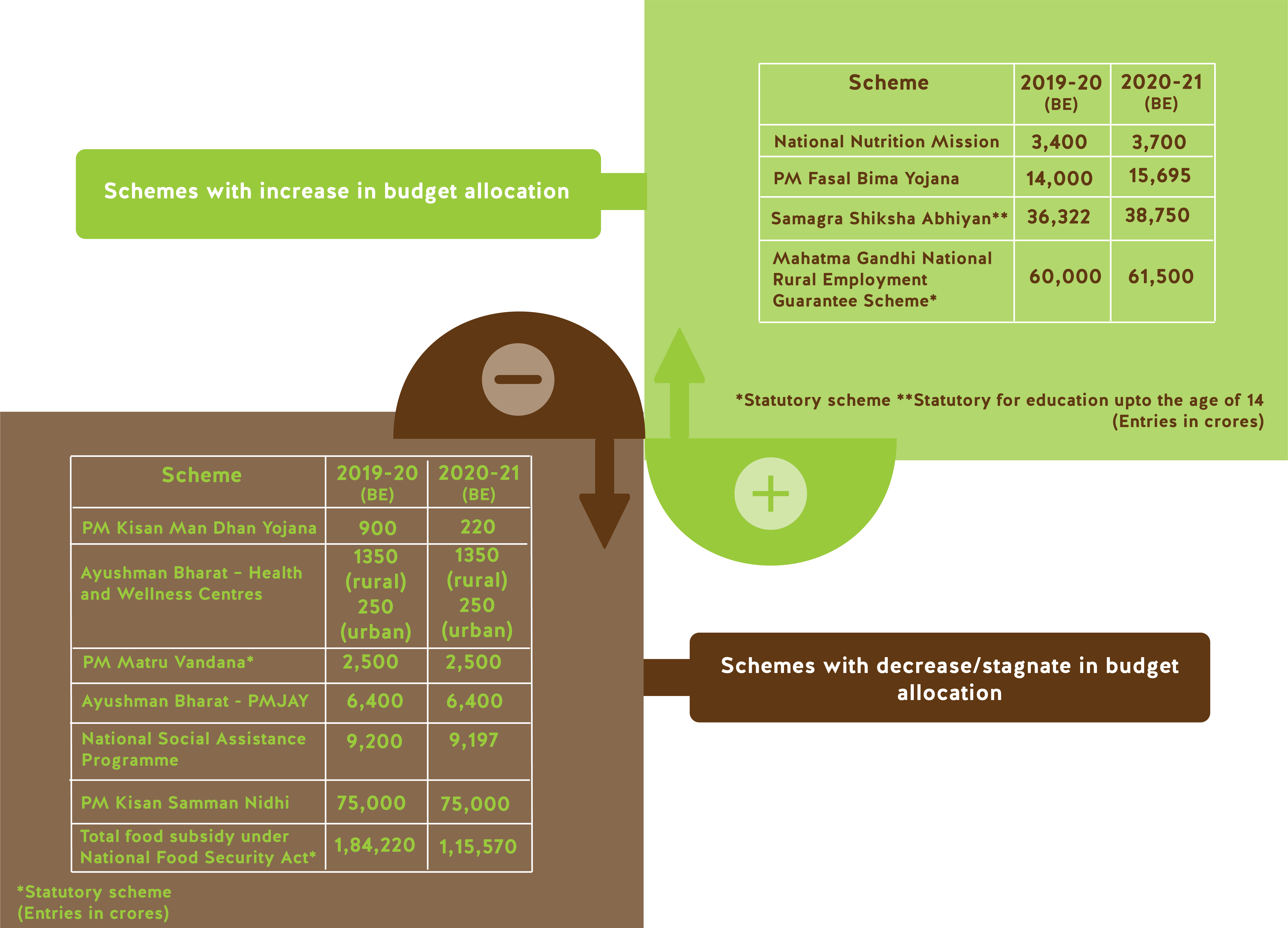

(Source here)

As seen above, there has been no significant increase in the allocations for major schemes. There has been an increase in the allocation for the PM Fasal Bima Yojana and for Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan. No change has been made to the allocation for Ayushman Bharat.

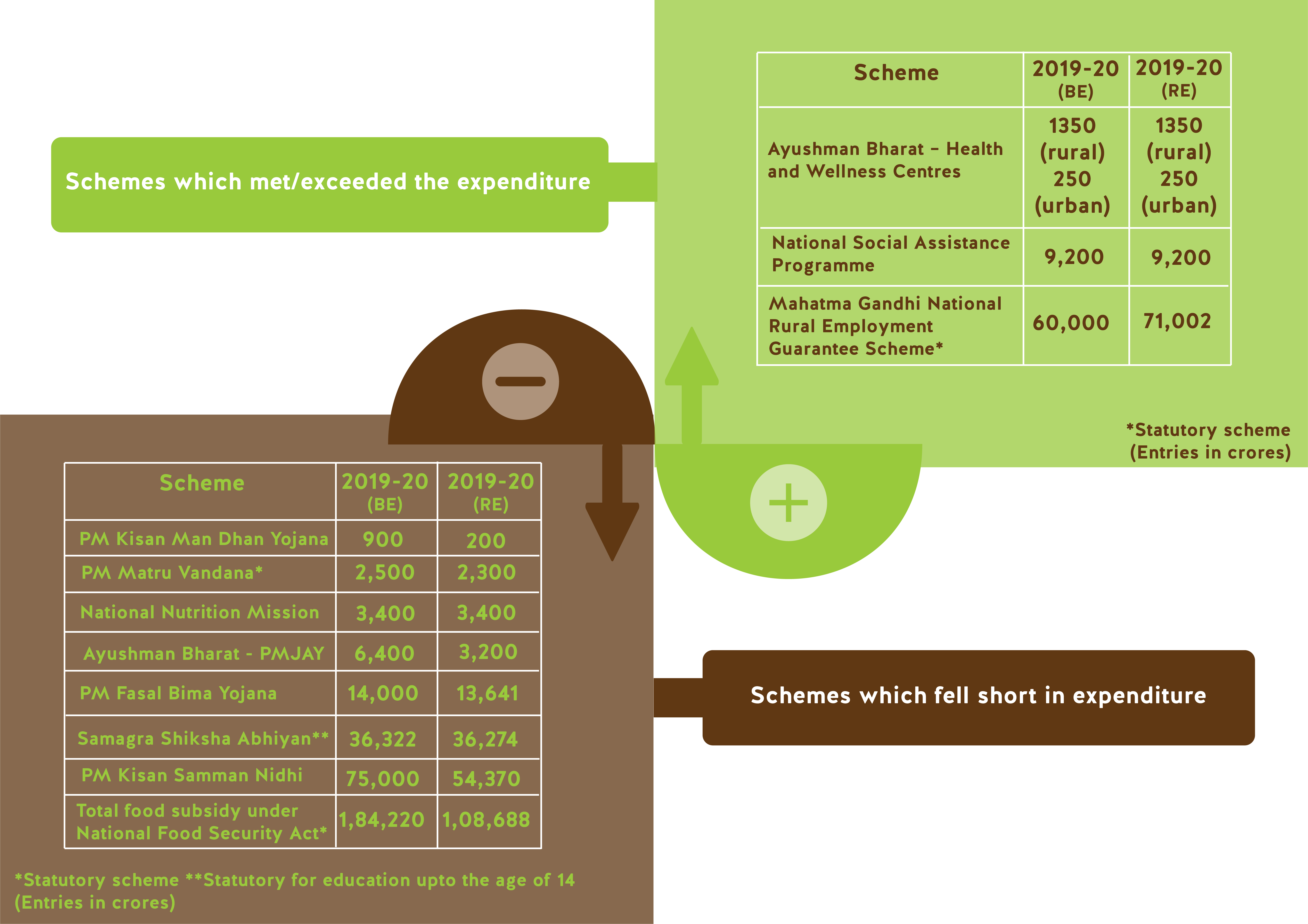

(Source here)

Further, as highlighted above, expenditure on many welfare schemes has been lower than the Budget Estimates for 2019-20. The Revised expenditure for PM Kisan, for instance, is 27% less than the Budgeted Expenditure. This figure goes up to 50% with Ayushman Bharat. Meanwhile, reports have suggested that the implementation of these schemes has been far from perfect. These reports, for instance, identify wide geographical variations in administering Ayushman Bharat, as well as numerous concerns with the disbursement of benefits under PM Kisan. The Budget numbers may, therefore, point to greater concerns with respect to the efficient implementation of schemes. It is important to note that there is no effective remedy for citizens seeking to enforce the implementation of schemes made by executive order – while the Indian courts have been proactive in identifying rights, there is little action by way of enforcing them.

We note that MNREGA and NFSA confer statutory rights. Schemes under these two acts can be enforced as a matter of right, unlike other schemes made by executive order. This, in turn, means that if a citizen seeks to enforce her statutory rights under either of these statutes, the state cannot justify its failure to do so on the ground that the funds allocated have run out. However, as we see above, there has been no significant increase in the allocations for MGNREGA, even though the Revised Estimates were far in excess of the Budgeted Estimates for 2019-20. There has further been a decline in food subsidies under NFSA. This is problematic, particularly in light of recent reports which have found that there is a funding crunch for MNREGA. Some states have run out of funds by January of the financial year, even as the Revised Expenditure for 2019-20 is well in excess of the Budgeted Expenditure for the same year. It is unclear whether the government will be able to fulfil its obligations under the two Acts within the budget allocated.

Finally, we note that the budget allocations do not provide an indication on the manner in which the funds will be spent. We note that the Budget has envisaged an expanded role for the private sector in providing essential welfare services, indeed, the Budget Speech expressly mentions Public Private Partnerships for setting up hospitals under the Ayushman Bharat scheme. Further, the Budget speech highlights the role of Direct Benefit Transfers as a key improvement in the delivery of welfare in India. However, as we have noted here and here, there is much room for improvement with these models of welfare delivery.

In the Budget Speech, the Finance Minister referred to the need to create a “caring society” as a guiding principle for the Budget allocations. While this is an important step in providing direction to policymakers, there is a pressing need to re-evaluate the way India currently Budgets for welfare.