The financial-legal framework envisaged by the FSLRC comprises nine important components, one of which is Micro-prudential regulation. Micro-prudential regulation refers to those regulations that concern the safety and soundness of financial service providers, with the intention of promoting stability and resilience of the Indian financial system. While all providers would be concerned about their institution’s health, there is a need for regulator-intervention in the form of regulations. The motivation for this is the protection of consumers as well as the mitigation of systemic risks, both of which are linked to each other in many ways in terms of outcomes. Therefore, as the FSLRC explains, these regulations are aimed at one firm at a time, in contrast to macro-prudential (systemic risk) regulation that involves the financial system as a whole. FSLRC describes two reasons for micro-prudential regulation:

- Governance failures within firms: These are failures that arise from the principal-agent problem between the managers and shareholders of the firm, where the shareholders (Board) may not have enough control over the managers’ (agent) actions which could be detriment to the interests of shareholders and customers.

- Moral hazard: Any indication of an implicit guarantee available from the Government in the event of failure of a financial institution would produce ‘moral hazard’ behavior on part of managers to take indiscriminate risk, or to make decisions for short-term gains with undesirable long-run repercussions for the institution.

These undesirable outcomes have added significance with respect to the financial system due to the balance sheet obligations some of the institutions make to their consumers (such as deposits placed by consumers in banks, or pension assets managed by pension funds), and also due to systemic risk concerns. The difficulty in bridging information asymmetry gaps between institutions and consumers make it impossible to address these issues in the absence of regulation.

Given micro-prudential regulations are expensive and intrusive, FSLRC has taken the view that these must be applied only where it is required, the intensity of which should be proportional to the nature of the issue to be addressed, and will be guided by the Draft Financial Code. FSLRC clarifies this point in the following manner: An institution that has balance sheet obligations to a small set of customers who are well-equipped to assess the credit risk of the institution, would face less stringent micro-prudential regulations than an institution having fixed balance sheet obligations to a large number of small retail consumers. Similarly, in those situations where informational asymmetries between institutions and consumers are very low and can be easily bridged due to the local nature of such institutions, there is a lesser requirement for such regulations. Also, all systemically important institutions identified by the FSDC will be subjected to micro-prudential regulation as specified by the respective regulator.

FSLRC has laid out principles that regulators must be guided by in framing micro-prudential regulations. Among others, these principles keep in mind the feasibility of implementation and supervision, the need to facilitate access to and innovation and competition in financial products and services, and the desire to minimize differences in regulatory approaches that target similar activities or mitigate similar risks.

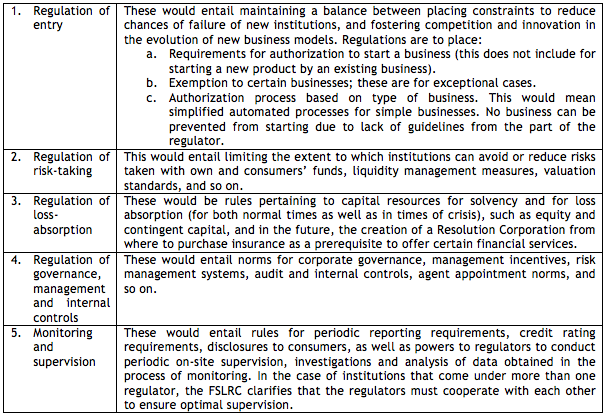

Micro-prudential regulations have been further categorized into the following:

In conclusion, FSLRC has envisaged micro-prudential regulations as a means to reduce but not eliminate the probability of failure of financial firms.

—

This post concludes our FSLRC Blog series. If you have any feedback for the authors or on the topic please do share in the comments section below or drop us a line at blog [at] ifmr.co.in

One Response

I think beyond consumer protection and asymmetric information, there is need to bring out the notion of political brokerage to balance out uneven countervailing power between the institutions and consumers, on the one hand, and between large institutions and small institutions, on the other.

There is also a need to understand cultural dimensions and the the need for political actors to determine what society would tolerate, irrespective of whether suppliers and consumers are willing to agree on. The subject of interest rates is one such issue. Even if borrowers decide that they prefer 40% interest rate to money lenders who charge even more, society may still consider this unacceptable. Therefore, the regulator needs to go beyond the interests of the contractual parties.