In this ongoing series, we will cover stories of citizens who have been excluded from social protection benefits delivered through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and Public Distribution System (PDS). In collaboration with Gram Vaani*, a grassroots-level social tech company, we document the stories of beneficiaries who have faced challenges in welfare access in M.P., Bihar, U.P., and Tamil Nadu.

In the wake of the economic distress caused by the COVID-19 lockdowns, both Central and state governments alike have heavily promoted the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) programme as a safety net for many individuals in rural India who have suffered a loss of livelihood.[1] However, issues related to delayed/inadequate wage payments persist in the programme’s implementation.[2] In this blog post, we cover the case of a daily wage worker in need of money, who turned to the programme, but failed to receive her wages on time. Such delays not only undermine the objective of the employment guarantee scheme but also result in additional burden for workers in the form of search and opportunity costs.

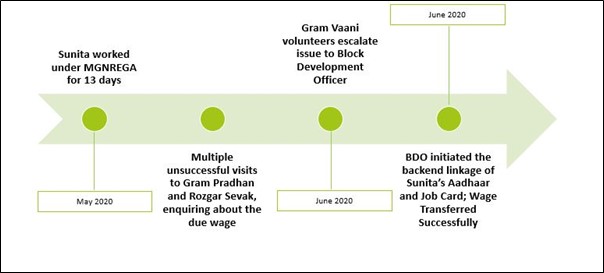

In May 2020, Sunita[3], a daily wage labourer looking to earn an income amidst the crisis, worked for 13 days under MGNREGA, digging a pond site in a village in Jalalabad, Uttar Pradesh. However, even after ten days of having finished the work allocated, she did not receive the wages due to her. In dire need of money, Sunita approached the local Rozgar Sevak as well as the Gram Pradhan (village head), asking for a status update on her due wage payment, but did not receive any clear response from either. The Gram Pradhan, evading the issue each time he was approached, cited budgetary issues as the reason for the delay and assured her that the money would soon arrive.

Field volunteers from Gram Vaani informed us that Sunita was not the only worker whose wages had been withheld/delayed under the programme in this period. Many people from the same village had been awaiting their payments for a long time. Given the scale of the issue, the volunteers recorded citizens’ grievance in an audio clip and circulated it among local functionaries, including the Gram Pradhan and the Rozgar Sevak. They also escalated the issue to the Block Development Officer (BDO), requesting him to expedite processing of the due wages, given that the affected workers had no other means of earning a livelihood. It was only then that the BDO, after checking with his office’s computer operator, informed the volunteers about the various reasons the workers had not been receiving their due payments. Reasons included lack of linkage between workers’ Aadhaar cards and their job cards, spelling errors in workers’ names, among others. A week after Gram Vaani broadcasted the audio clips, the due wages arrived in the bank accounts of the aggrieved workers.

While the case has now been resolved, it demands a closer look at why the wages had not been processed until external pressure by a civil society organisation had been applied on the local administration. The volunteers informed us that the issue had arisen because of lack of staffing capacity at the Block Development Office. While the Aadhaar card copies had been collected for all workers by the concerned Rozgar Sevak long ago, the linking of Aadhaar to workers’ job cards (typically done at the back-end by the computer operator at the BDO’s office) had been pending. For this particular block, there was only one computer operator who was responsible for carrying out this exercise for all villages, resulting in major backlogs. It was only after the volunteers had explained the urgency of releasing MGNREGA wages for workers they represented that the concerned file for that particular village was processed on priority at the block office.

This highlights certain legacy issues that have characterised delivery of benefits across schemes. It brings to surface the typical bureaucratic delays and the negotiation that a citizen must undertake with government officials to “push” a given file to get one’s work done, despite the introduction of digitised databases and online transfers. Secondly, in addition to such procedural delays, the case highlights the lack of a streamlined system within the G2G (government to government) domain. The Rozgar Sevak and the Gram Pradhan, two key functionaries closely involved in implementing the MGNREGA programme in a village, have no authority over the release of wage payments and are often unaware of the actual status of funds. In this case, when approached, both officials had stated that they had duly completed what was required from their end (supervising work, issuing payment orders, and forwarding the same to the BDO) and had no authority or information about the crediting of workers’ bank accounts. This partial decentralisation of functions is a disconcerting feature because such functionaries are also among the most proximate points of contact for workers seeking information about their entitlements or expressing their grievances. While this lack of authority related to payment processing might help ensure that funds are not misappropriated by local functionaries, it has complicated the process of seeking redressal of issues related to wage payments.

The resolution pathways employed by the volunteers in this case also signal the low prevalence/uptake of official grievance redress mechanisms. In the absence of an intermediating civil society organisation, workers would have had to run from pillar to post, searching for information about delayed payments, with no specific route towards easy resolution. According to recent MGNREGA social audit reports, in the 10,416 Gram Panchayats that were social audited at least once in the last year, it was found that out of 2,688 grievances reported in 2020-21, only 227 or 8.44 per cent of such grievances could be closed (it must be noted that this ‘closed’ status does not necessarily indicate that the citizen’s grievance was resolved).[4]

This is not just symptomatic of poor enforcement of scheme guidelines but also of the general problems workers face while interacting with state machinery that is not proactive in addressing their concerns. As per Section 19 of MGNREGA, the state governments have been assigned with the responsibility of determining “appropriate grievance redressal mechanisms at the block and district level for dealing with complaints”.[5] Despite this, grievance redress mechanisms in MGNREGA continue to remain toothless for a variety of reasons. The establishment of GRM under the Act has been left completely up to the state governments, resulting in poor enforcement by many state governments. As of 2018, only 20 states and 1 Union Territory had formulated Grievance Redressal Rules for dealing with complaints.[6] Even when some form of redress architecture exists, cumbersome modalities (such as a written application) coupled with the lack of timely follow-up action by officials discourage workers from filing complaints officially. Additionally, a recent study by Libtech revealed that the routinisation of the issue of delayed payments has led to workers not perceiving months-long delays to be a violation of their rights under the Act.[7]

Another key theme that emerges from this case study pertains to the capacity of local government functionaries who form the citizen-interface of most welfare schemes. Concerted efforts towards increasing their capacity should not only include expansion of their roles and functions but must also entail a numeric increase in the staff at key government offices to ensure better delivery of entitlements in the last-mile.

Figure 1: Timeline of Exclusion

*The author would like to thank Aaditeshwar Seth, Sultan Ahmad, Matiur Rahman, Ashok Sharma, and the Field Operations team at Gram Vaani for facilitating these case studies.

A working framework to study exclusion in social protection has been employed to analyse this case, mapping points of exclusion across the four key stages of scheme design and delivery.

[1] MGNREGA in Need. (2020). The Indian Express. Retrieved from https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/editorials/mgnrega-demand-rural-labours-migrant-workers-coronavirus-6441371/

[2] Chakrabarti, A. (2021). ‘Inordinate delay’ in release of funds for MGNREGA workers discouraging — Parliamentary panel. The Print. Retrieved from https://theprint.in/india/governance/inordinate-delay-in-release-of-funds-for-mgnrega-workers-discouraging-parliamentary-panel/620037/

[3] The name of the respondent has been changed.

[4] The Pandemic Has Happened Social Auditing of MGNREGA. Retrieved from Inclusive Media for Change: https://www.im4change.org/news-alerts-57/pandemic-impacted-social-auditing-of-mgnrega.html

[5] Section 29 of Schedule 1 in the Act states that effective grievance redressal mechanisms must be established, including “institutional mechanisms for receiving grievances as and when they arise, while fixing one day each week 30 of Schedule I in the Act states that there shall be an Ombudsperson for each district for receiving grievances, enquiring into, and passing awards as per guidelines issued. For more details, see the full text of the Act.

[6] Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India. (2018). Grievance redressal under MGNREGS. Retrieved from https://rural.nic.in/press-release/grievance-redressal-under-mgnregs

[7] Libtech India (2020). Length of the Last Mile. Retrieved from http://libtech.in/length-of-the-last-mile/

Cite this item

APA

Gupta, A. (2021). Delays in Processing of MGNREGA Wage Payments. Dvara Research Blog.

MLA

Gupta, Aarushi. “Delays in Processing of MGNREGA Wage Payments.” Dvara Research Blog (2021).

Chicago

Gupta, Aarushi. 2021. “Delays in Processing of MGNREGA Wage Payments.” Dvara Research Blog.