The National Health Mission (NHM) is a centrally sponsored scheme driving multiple initiatives aiming for better health outcomes. The 2021-22 Union budget allocated Rs 36,576 crores to the scheme out of the total health budget of Rs 73,932 crores. With more than 50% of the health budget dedicated to this scheme, it is important to assess its performance. Our previous work has evaluated centrally sponsored schemes (CSS) and their effect on centre-state financial relations. In this post, we look at one such CSS scheme and its rigid fund devolution architecture that has reduced states’ autonomy in implementing the scheme.

Before 2005, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare administered multiple programmes for healthcare without integration leading to duplicated efforts and wasted resources. This led to the introduction of the National Rural Health Mission to create a comprehensive system combining all the health efforts by the government and to build the capacity of health systems in rural areas. Subsequently, the National Urban Health Mission was introduced in 2013 to target the urban poor, and the NHM subsumed the two missions in 2013.

Objectives and Initiatives of the Mission

The NRHM sought to prioritise healthcare access to the vulnerable sections of the rural population by increasing the reach of medical services to hitherto unserved or underserved areas by providing mobile medical units. The program identified 18 high-focus states for special attention due to their low health indicators or weak health infrastructure. Health system strengthening, construction/upgradation of health facilities (like primary health centres) was adopted as a key component of the program. While non-high focus states were given a ceiling of 25% for such civil works, the high-focus states were allowed to use 33% of the total NRHM outlay for the same, owing to their limited infrastructure capacity. Along with infrastructure, human resource development was undertaken by skilling community level workers[1] and increasing their presence, especially in the high-focus states, to act as the first point of contact for the community for their health needs.

Similarly, the NUHM was adopted with the objective of providing healthcare to the poor and disadvantaged sections in urban areas. Considering the issues of poor sanitation, lack of drinking water and cramped living conditions, it sought to improve access to preventive and promotional care to slum dwellers by converting the existing primary health facilities into Urban Primary Health Centres (U-PHC). In line with the objectives of NRHM and NUHM, five programmatic components were devised under NHM- health systems strengthening, reproductive health services, communicable and non-communicable diseases programs and infrastructure maintenance. The National Health Mission has continued providing special attention to the 18 high-focus states for all its programs.

Planning and Approval Process

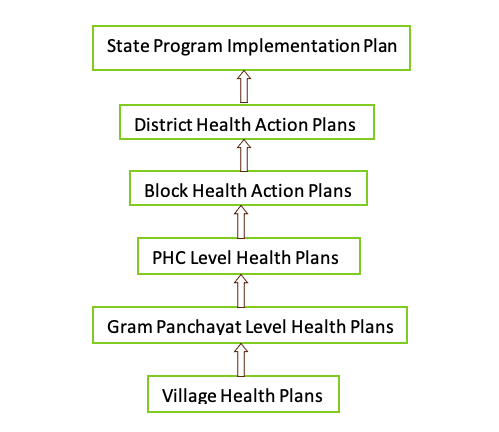

The NRHM has a decentralised approach to the planning and budgeting process wherein plans are formulated at different levels and integrated into the final state program implementation plan (SPIP). This process is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1: Planning Process

According to these State ProgramImplementation Plans (SPIP), the allocation to states is determined by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Further devolution to the districts is sanctioned based on the District Health Action Plan submitted by them to the state level and so on. A similar process is adopted for the fund devolution under NUHM.

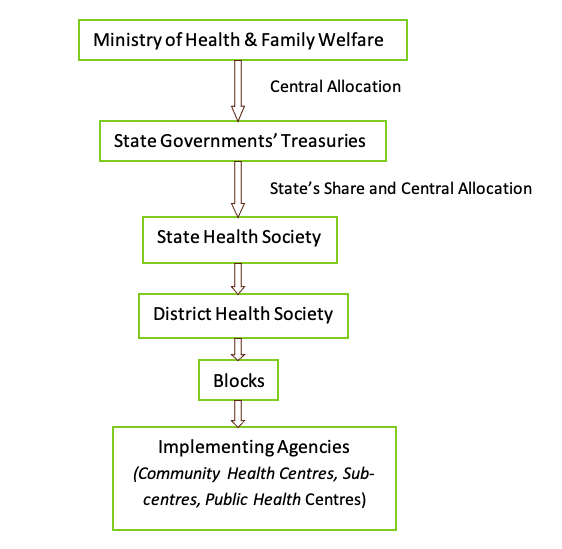

Fund Devolution under the Mission

Being a Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS), the funding for NHM is split between the centre and states in the ratio of 60:40 for general states and 90:10 for special category states[2] respectively, following the 14th Finance Commission. The funds are transferred to flexible pools (called flexipools) for each programmatic component to provide financial flexibility and promote efficient fund utilisation. The states are provided flexibility to allocate funds across strategies under the flexipools “as per local needs and broad national priorities”.The latter, however, is under greater emphasis with the mandate to spend funds under the national program initiatives. The release of funds is also conditional on the utilisation of funds in the previous year for the purpose they have been given. The Ministry inspects the performance of states through utilisation certificates and audits while deciding on sanctioning further grants. The devolution of funds under the Mission to the lower levels (Figure 2) is sanctioned according to the plans submitted and approved as part of the SPIP (Figure 1).

Figure 2: Fund Devolution Pathways

Accumulation of Unspent Funds with the States

A CAG audit in 2017 reported delays of 50 to 271 days for the transfer of NRHM funds from the state governments to the state health societies. A study has documented that in Bihar and Maharashtra, the reason for delays could be the long process of fund release. For instance, there are 32 and 25 desks respectively through which file movement occurs for fund release to the state health societies (SHSs). The delays in the devolution of funds might explain the low expenditure and the large amount of unspent funds lying with the states. The overall health expenditure by states under NHM as a percentage of the total available NHM funds was at an average of 56% for 2016-17and remained at 59% in 2018 and 2019. This low health expenditure is also corroborated with the presence of an unspent balance under the NHM at Rs 12,594 crore in 2018-19. The graph below shows the expenditure of overall NHM funds by some of the high performing states (Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Punjab) and the low performing states (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar)based on their DALY rates[3]. Barring Tamil Nadu, fund utilisation has remained between 50-80% for both low performing and high performing states.

Graph 1: State Expenditure under NHM

Along with delays in the devolution of funds to the SHSs, the accumulation of funds also occurs at the society level. The Comptroller & Auditor General’s 2017 report on Reproductive and Child Health under the NRHM reported the states’ spending of NRHM funds from 2011 to 2016. The Ministry records indicated that 1,06,179.78 crore out of 1,10,930.30 crore was spent by the SHSs over this period. However, accounting for the interest accrued on the unspent funds lying with the societies, by 2016, Rs 9509 crores was left as an unspent balance with the SHSs (see graph 2).

Graph 2: Accumulation of Unspent Balance with the State Health Societies

The Ministry attributed this unspent amount to include advances paid for construction projects and funds used for maintenance. There were discrepancies like the diversion of funds for other projects, outstanding advances and certificates, and releases without the approval of the SPIPs in some states.

Complicated Fund Devolution

While the devolution of funds seems simple in figure 2, the actual transfer to bodies below the state health society occurs through multiple bank accounts for each flexipool. Choudhary and Mohanty, in their 2018 paper, documented the rigidity in the scheme’s financial architecture through interviews and data provided by government officials in Bihar, Maharashtra and Orissa. They found that despite being termed “flexipools”, the fund devolution and expenditure is strictly segregated within the programmatic divisions. Other than lack of flexibility in fund utilisation across pools, rigidity is observed within the pools for specific initiatives. For example, funds have been earmarked under each of the disease control programs (like tuberculosis, leprosy) under the communicable diseases programme and are released separately by the Health Ministry. This segregation of funds into each scheme reduces the state’s ability to allocate funds according to its healthcare priorities. Notwithstanding the state’s requirements, funds have to be spent in the nationally defined programs irrespective of the local context.

Along with separate reporting for each program, funds are segregated and transferred to multiple bank accounts. This complicates the process of utilisation of funds with separate financial reporting for each budget head. Hence, the rigid requirements for fund utilisation can reduce efficiency by restricting the state’s flexibility to spend resources. While the planning and budgeting process for the scheme is carried out in a bottom-up manner, flexibility in guidelines for implementation would help states spend the allocated amount in their respective context.

The rigid fund devolution pathway of the scheme and its subsequent bleak implementation throws light on the restricting effect centrally sponsored schemes can have on the state’s ability to execute development initiatives. While the union executive is instrumental in setting down national priorities for social welfare, including states in the decision-making stages and providing them flexibility in implementation would help achieve better outcomes. As seen in the case of NHM, the lack of autonomy has led to low expenditure, hence accumulating the public’s money in government coffers. Bringing in the states’ perspectives will help translate the scheme’s objectives into results on the ground to address citizens’ healthcare needs.

[1]Like ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists), ANMs (Auxilliary Nurse Midwives) and AWWs (Anganwadi Workers).

[2]The special category states are the eight north-eastern states and the three hilly states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, identified on the basis of their low resource base.This makes them eligible for greater central assistance through funds and concessions.

[3]DALY (Disability Adjusted Life Years) depicts the number of years lost due ill-health, disability or early death which indicates the disease burden of a population. The low performing states were chosen due to their high DALY rates of Uttar Pradesh (39585), Madhya Pradesh (37678) and Bihar (37074). Similarly, the high performing states were chosen based on lower DALY rates (below Indian average of 35435): Kerala (27301), Tamil Nadu (33527) and Punjab (33766).

References

Choudhury, M., and Mohanty, R.K. (2019).Utilisation, Fund Flows and Public Financial Management under the National Health Mission.NIPFP Working Series. https://www.nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2018/05/WP_2018_227.pdf

Choudhury, M., and Mohanty, R.K. (2020).Role of National Health Mission in Health Spending of States: Achievements and Issues. NIPFP Working Paper Series. https://nipfp.org.in/media/medialibrary/2020/08/WP_317_2020.pdf

Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances. (2017). National Health Mission (NHM): Manual for District-Level Functionaries. https://darpg.gov.in/sites/default/files/National%20Health%20Mission.pdf

India State-level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. (2017). Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transitions across the states of India, 1990-2006 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet, 390 (10111), 2437-2460. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)32804-0/fulltext

Kumar, A. (2020). Centrally Sponsored Schemes and Centre-state Relations: A Comment. Dvara Research. https://dvararesearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Centrally-Sponsored-Schemes-and-Centre-state-Relations-A-Comment.pdf

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (nd). National Rural Health Mission: Framework for Implementation 2005-2012. https://nhm.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/nrhm-framework-latest.pdf

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (nd). Chapter3:Funding for the Programme in Annual Report of the Department of Health & Family Welfare for the year 2013-14. Publication Archives. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/documents/publication/publication-archives

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2013). National Urban Health Mission: Framework for Implementation. http://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NUHM/Implementation_Framework_NUHM.pdf

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2016). Operational Guidelines-Financial Management: Annexure II. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/about-us/departments/departments-health-and-family-welfare/nhm-finance/nrhm-rch-flexible-pool/rch-flexible-pool/frame-work-guide-lines-advisories/operational-guidelines-financial-management

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2017). Guidelines for Financial Management under NUHM. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NUHM/NUHM_FMG_Guidelines.pdf

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. (2017). Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Performance Audit of Reproductive and Child Health under National Rural Health Mission. https://bit.ly/3vmuDCD

National Health Mission. (2021). Quarterly NHM MIS Report (Status as on 31.12.2020).http://nhm.gov.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=457&lid=686

PRS Legislative Research. (nd). Demand for Grants 2021-22 Analysis: Health and Family Welfare. https://prsindia.org/budgets/parliament/demand-for-grants-2021-22-analysis-health-and-family-welfare

Shah, S., Junnarkar, R., and Kapur, A. (2019). National Health Mission (NHM): GoI, 2019-20. Budget Briefs, 11(4). https://accountabilityindia.in/publication/national-health-mission-nhm-2/

Shah, S., Kapur, A., and Andasu, A. (2020). National Health Mission (NHM): GoI, 2020-21. Budget Briefs, 12(6). https://accountabilityindia.in/publication/national-health-mission-pre-budget/

Vishnu. (2013). Special Category status and centre-state finances. The PRS Blog. https://www.prsindia.org/theprsblog/special-category-status-and-centre-state-finances

Cite this item

APA

Nambiar, A. (2021). National Health Mission: Rigid and Complicated Fund Devolution Leading to Underutilisation . Retrieved from Dvara Research Blog.

Chicago

Nambiar, A. (2021). National Health Mission: Rigid and Complicated Fund Devolution Leading to Underutilisation . Retrieved from Dvara Research Blog.

MLA

Nambiar, Anjali. “National Health Mission: Rigid and Complicated Fund Devolution Leading to Underutilisation .” 2021. Dvara Research Blog.