Home > The Making of Trust

In this study, we explore how borrowers build trust in digital lenders amid the rapid growth of India’s digital credit ecosystem. Read our full paper here.

The presence of digital credit is expanding in India. In 2021, India had nearly 1,100 unique loan apps across various platforms. However, more than half of these were found to be illegal- they operated without proper licensing, promised quick loans without paperwork at questionable terms such as exorbitant interest rates, hidden fees, and used unethical, coercive recovery methods. These practices are in stark contrast with the customer protection guidance offered by the regulator to regulated lenders.

However, at a first pass, it is difficult for customers to differentiate between the two types of lenders—their app designs and user interfaces are often indistinguishable. Assuming borrowers have an inherent preference for more ethical, regulated entities, enabling borrowers to distinguish between the unethical, illegitimate and ethical, regulated lenders is instrumental to effective customer protection in the boundless landscape of digital lending. The ambition of empowering prospective borrowers to identify exploitative digital lenders and defend themselves from those lenders, necessarily, raises two questions: what are the expectations that prospective borrowers have of trustworthy lenders and, how borrowers gauge the trustworthiness of a lender.

An enquiry into the first question allows us to appreciate trust-as-a-process. It surfaces principles and practices that help digital lenders become worthy of customers’ trust. The second question concerns itself with how digital lenders can communicate their trustworthiness to customers. This becomes a pressing issue when the borrower and the lender do not have a prior relationship, and even more important when the borrower is a first-time user of digital credit. Data suggests that about 140 million Indians became first-time borrowers between 2019 and 2022. A significant portion of these new credit customers are low-income households earning under Rs 2.8 lakh per year, with digital lenders playing a key role in serving them. This study focuses on how lenders can become worthy of borrowers’ trust. In the order of questions, this must be wrestled with first because enabling lenders to communicate trustworthiness without them actually becoming trustworthy would be a bigger disservice to the customer protection agenda.

The study seeks to understand how customers trust and contract with a digital lender. Uncovering what people mean by trust by directly asking them about it can be difficult, partly because the word trust has a dual nature- it is both a noun and a verb. Owing to this dual nature, it is difficult to define trust without implicating trust itself. Instead, we attempt to study trust in terms of the proximate grounds that people rely on to trust someone or something. To explore the proximate grounds customers rely on to trust digital lenders, we commenced a mixed-methods study of DFS users in early 2024. The study is supported by qualitative interviews spanning a range of topics from what trust meant in personal relations and financial transactions to the obligations that come with being considered trustworthy. This is complemented by an experiment where respondents assess the user interfaces of digital lending apps for trustworthiness. Based on our discussions with DFS users, we develop a theory to explain the making of trust in digital lending.

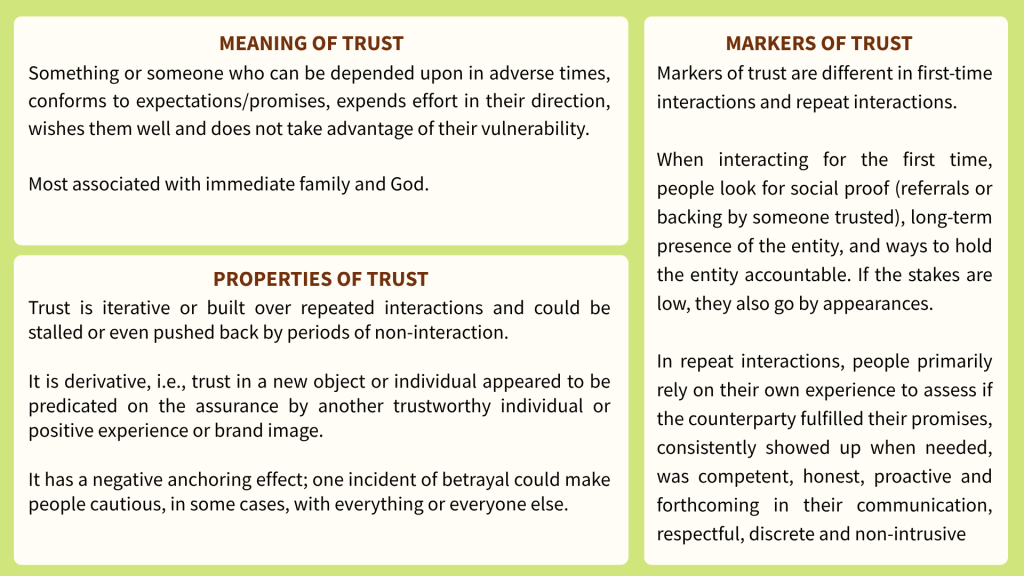

To trust someone or something, people rely on several proximate grounds that give them predictability to base their future expectations. When a prospective borrower encounters a lending app for the first time, trust is implicated at different stages in the user journey. Building on findings from the qualitative enquiry into people’s notion of trust, we model the formation and reinforcement (or depletion) of people’s trust in a specific digital lender as a composite of trust formed across three key stages of user journey in the decision to choose a specific digital lender, during the loan cycle and post-loan cycle.

Trust at each of these stages is composed of a set of factors associated with the borrower, lender and the circumstances within which decisions are made. What factors influence trust decisions at different stages? How do they interact to arrive at certain levels of trust? Read the paper here.

| When? | March – April 2024 |

| Where? | Thane, Ghaziabad, Ahmedabad |

| Who? |

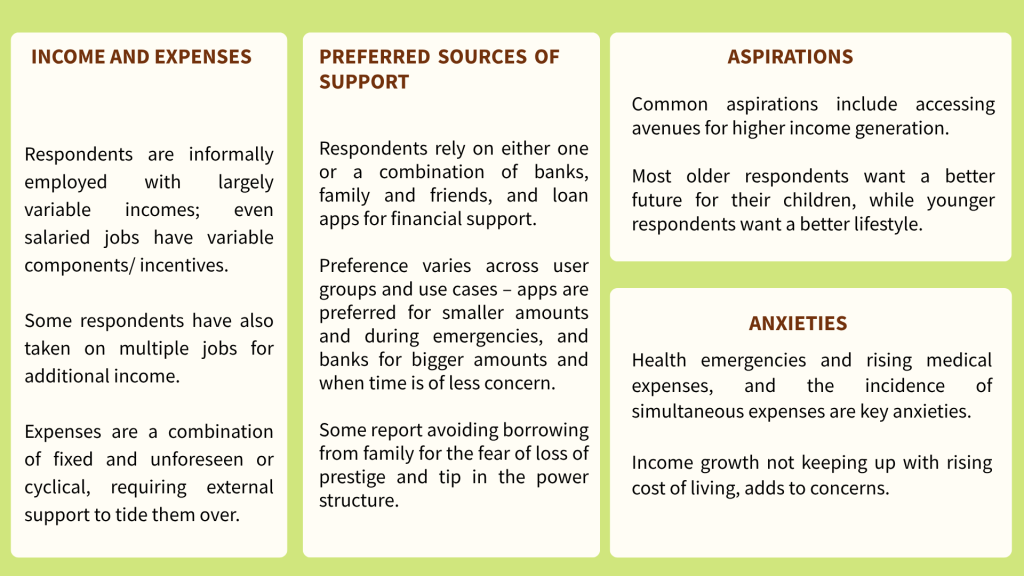

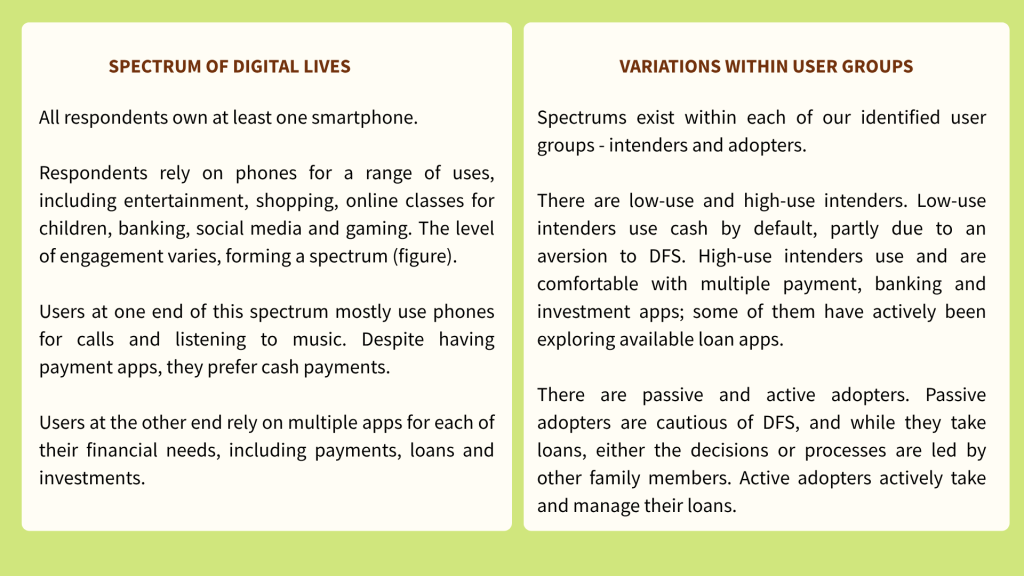

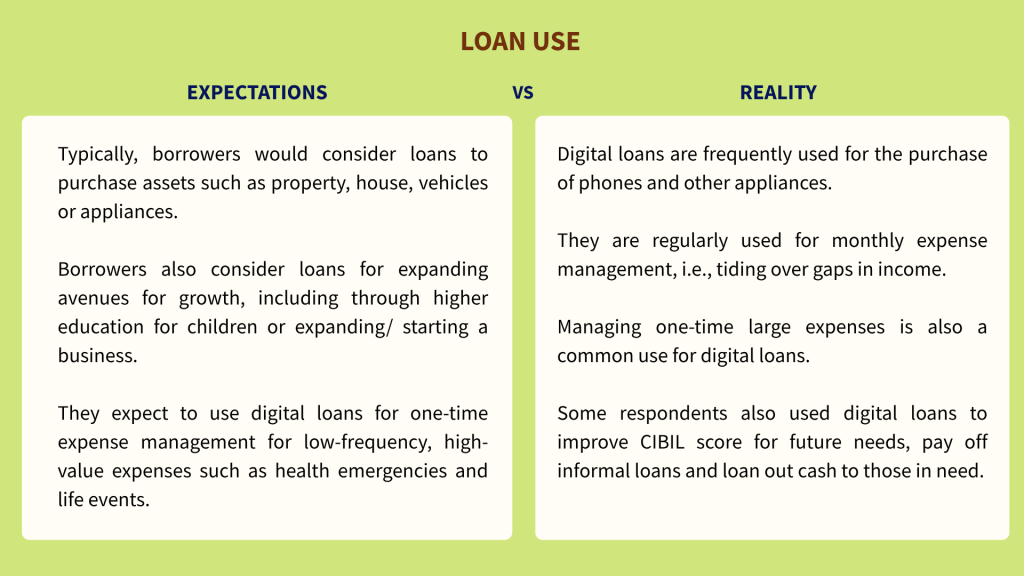

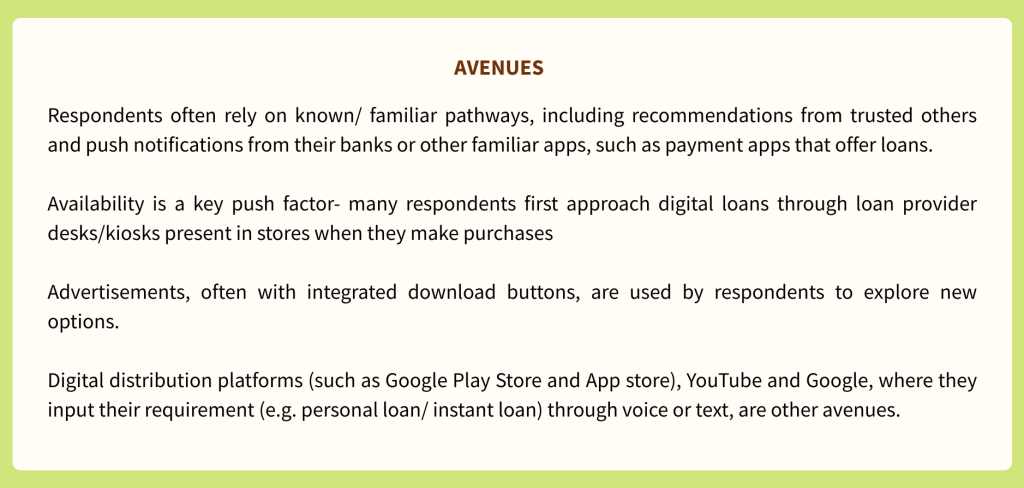

Categories of DFS users – adopter (familiar with/ have used digital payments and have/ completed a digital loan in the last year) and intender (familiar with/ have used digital payments) Households with an annual income of less than Rs. 5 lakh |

| How? | A combination of semi-structured in-depth interviews (IDI) and focus group discussions (FGD) – 9 each |

| What? | Respondents were asked about their mobile usage, how they handled finances, their idea of trust across several domains and their perceptions of and engagements with different loan sources, followed by a stimulus to gauge how they perceived sample digital lending apps |

| Sample = 65 | |

|---|---|

| Centre | |

| Ghaziabad | 21 |

| Noida | 44 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 46 |

| Female | 19 |

| User | |

| Intender | 20 |

| Non-Intender | 45 |

Read the full blog here.

In our previous blog, we discussed how the intent to trust being implicated in the act of trusting makes it difficult to define trust. Instead, a more feasible approach would be to study the factors that a potential customer (for adoption) or an existing customer (for continued usage) can base their expectations of DFS on or in other words, the proximate grounds to trust DFS. In this blog, we attempt to identify some of these proximate grounds of trust.

Read the full blog here.

In all our research efforts, we strive to maintain an independent voice that speaks for the low-income household and household enterprises. Our ability to perform this function is significantly enhanced by our commitment to disseminate as a pure public good, all the intellectual capital that we create.