A panel survey was conducted by Social Protection Initiative at Dvara Research with 12 partner organisations to understand whether low income, borrower households were able to (a) register to receive benefits, (b) receive credits in their accounts and (c) withdraw benefits received. In this post, we highlight the need for understanding the results of panel survey on welfare transfers from a process evaluation perspective to identify the fault lines.

The nationwide lockdown was first imposed in the wake of COVID-19 on the 23rd of March, and it was extended till the 31st of May, while till today regional lockdowns continue to be imposed on specifically identified containment zones. This prolonged lockdown has made it difficult for 77% of the Indian population who are engaged in the informal economy to make their ends meet. In response to the economic implications of the lockdown, the Government announced a 1.7 lakh crore relief package under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY) three days after the nationwide lockdown was imposed in March 2020.

In light of the lockdown and measures announced by the Government, earlier, in this policy brief, we looked at some of the potential measures to protect the informal sector workers from the economic consequences of COVID-19, followed by another policy brief, in which we looked into the issues likely to arise in last-mile delivery of PMGKY and provided our recommendations to fix it. Further, in this blog post, we looked at ways to expand insurance coverage under PMGKY.

As a part of our ongoing efforts to track the impact of the lockdown on the poor and to understand the reach of policy responses during the lockdown, we surveyed a cohort of 347 microfinance borrower households across 9 states on a monthly basis between April and June[1]. This post examines the results of the panel survey.

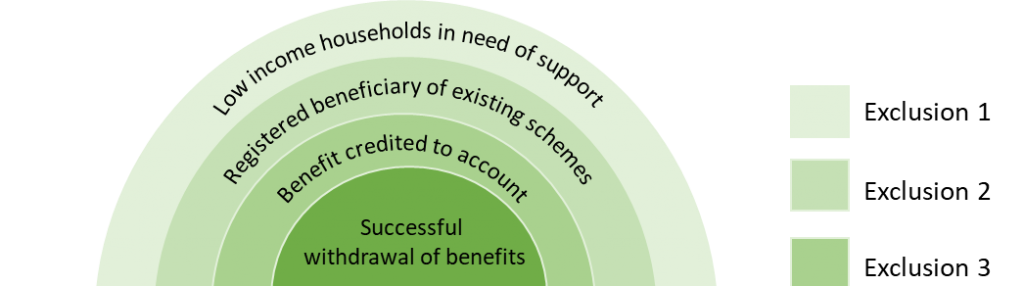

The path to successful receipt of cash transfers

Cash transfers made as part of PMGKY rely on the Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile infrastructure of existing schemes. To access benefits, one needs to be a registered beneficiary of its constituent schemes. Followed by which beneficiary accounts must then get successfully credited with cash transfers, where recipients can finally be able to collect these cash benefits from cash-out points. We found that there are exclusions at each of these levels, resulting in beneficiaries not able to receive PMGKY benefits.

Fig.1: Steps to receive government transfers and possible avenues for exclusion

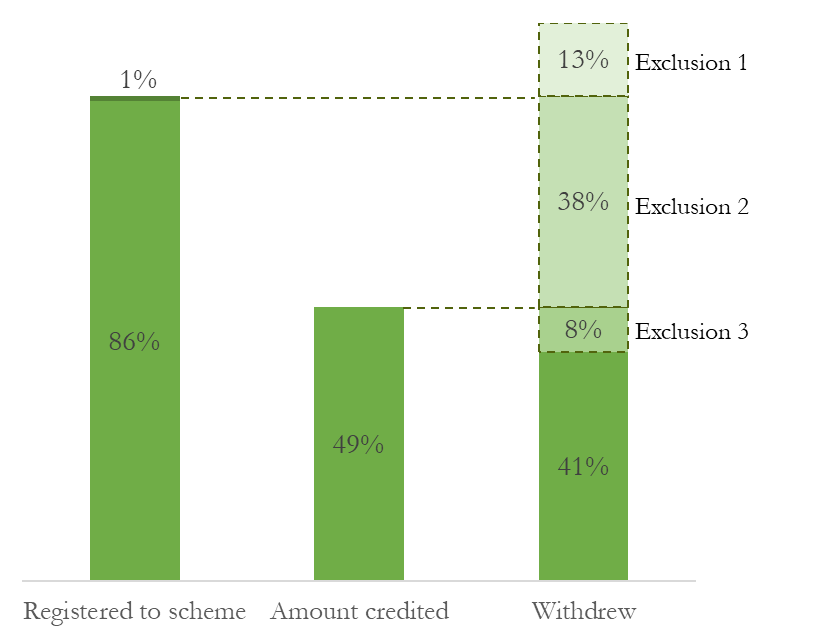

Only less than half of the surveyed households were successful in accessing cash transfers

Fig. 2: Access to cash transfers

Exclusion 1: Exclusion due to non-enrolment

The panel survey was purposively sampled to include only microfinance borrower households. The sample thus includes low-income households, engaged primarily in agriculture, daily wage work, casual labour or small trade, who have some kind of access to financial systems. While not all households surveyed necessarily fall below the poverty line, this is a segment that has suffered due to the lockdown nonetheless, with only 19% of households engaged in any income generating activity in April. However, 13% of the households surveyed stated that they were not registered for any of the constituent schemes of PMGKY, automatically excluding them from Government support through PMGKY.

While fresh enrolments and updation of relevant documents during lockdown are theoretically possible, in practice, they are next to impossible. Restrictions on movement, especially in the early stages of the lockdown, made it difficult for people to step out to go to any service points (Common Service Centres (CSCs), panchayat offices, etc.) to enrol in schemes or update documents. Additionally, not many CSCs were open for service during this time. Our survey found that only 33% of the households had access to CSCs in April, which is close to a month after PMGKY announcements. Three months after lockdown, a third of the respondents continued to report a lack of access to CSCs.

In addition to the central transfers through PMGKY, states too announced a set of relief measures to support the more vulnerable sections. Some of these measures took the form of temporary relaxations of conditions leading to the enrolment of more beneficiaries into existing schemes. The process of identifying beneficiaries varied across states. Chhattisgarh, for instance, adopted a self-declaration system by the beneficiary to distribute free ration. In Rajasthan, the Aadhaar database was used to identify poor households with no social security benefits for one-time cash transfers. While these efforts are laudable, we cannot tell from our survey whether these interventions have produced substantial drops in exclusion errors of type 1, i.e. exclusion due to non-enrolment.

Exclusion 2: Exclusion due to non-receipt of benefit

The problem here is two-fold: either the benefit has not been credited to the beneficiary account or the beneficiary has no information about a transfer despite his/her account being credited.

In the first case, errors in the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) architecture could lead to a failure of account credit. Given the number of institutions and mechanisms involved in DBT, it is often difficult to identify the source of errors. In a notification issued by the Ministry of Finance in 2019, a set of reasons for transaction failures were identified with directions to reduce the rate of such failures. Some of the major reasons identified include issues in Aadhaar seeding, lack of updation of NPCI mapper by the bank, seeding of wrong account types, etc. In each case of non-credit of cash transfers, beneficiaries have very few ways of knowing why they have not received due benefits.

In the second case, despite the credit of cash transfers, the beneficiaries may have received no information from banks. Often the accounts may not be linked to the current mobile numbers of beneficiaries, therefore, unless they go to a transaction point, they may have no way of knowing about such cash transfers. In addition to this, the lack of awareness regarding entitlements exacerbates the problem.

Exclusion 3: Exclusion due to inability to withdraw the cash transfers received

Restrictions on movement posed by lockdown conditions and lack of access to a functioning transaction point within reach prevented people from collecting the cash received. About a third of the households surveyed lacked access to any kind of banking outlet (bank, ATM, BC) in April. While the situation improved with the gradual lifting of lockdown, 20% of the households continued to lack banking access even in June. Additionally, even when the outlets are open, operational issues such as insufficient funds, technical issues, transaction failures due to a load of higher DBT volume, can lead to people having to return home without collecting their benefit.

Additionally, we observed that 26% of the sample while able to access cash transfers, received much lesser than the amount they should have received given the schemes they were registered in[2].

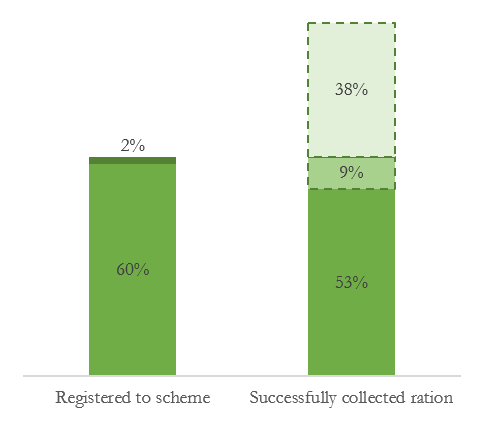

The relative success of PDS

With 53% of the surveyed households successfully able to collect ration benefits announced (Fig.3), in-kind transfers seem to have had better success in reaching poor households than cash transfer schemes. We have considered only those categories for whom benefits were announced during the lockdown. The actual number of PDS beneficiaries in the sample is much higher. Similarly, surveys conducted by other organisations during this period (see here, here and here) also found exclusions to be much lower for in-kind transfers than for cash transfers. It is also interesting to note that, some of the successful cash transfers utilised the PDS infrastructure to deliver cash to beneficiaries, as in the case of Tamil Nadu.

Fig. 3: Access to in-kind transfers

Research studies have unearthed the real level of exclusion at different points along the pipeline of welfare delivery[3]. The ongoing crisis has made these critical gaps in the system more prominent. Identifying the reasons behind the incidence of these failures and finding solutions for these beneficiaries should be our top priority.

The panel survey findings and live report can be accessed here and here, respectively.

[1] The COVID-19 Impact on Daily life survey is an ongoing panel telephonic survey conducted on a monthly basis, in partnership with 12 MFIs. The survey covers households in about 47 districts from 9 states. Round 1 was conducted in April, round 2 in May and round 3 in June.

[2] The minimum here is at least one instalment of the central contribution of benefits.

[3] See (Kodali, 2020), (Saxena, 2015), (P & Gupta, 2019)