The Finance Minister, in his budget speech for 2015-16, has announced a new defined benefit pension scheme – Atal Pension Yojanai (APY, henceforth) – for unorganised sector workers who are not covered under any statutory social security scheme. It has been proposed that the existing subscribers of National Pension System-Swavalamban (NPS-S), the extant pension scheme for the unorganised sector, be automatically migrated to the APY unless they voluntarily opt out. Under the NPS-S, launched in September 2010, the Government of India currently contributes Rs. 1000 per year to every subscriber who makes a minimum contribution of Rs. 1000 per year towards building a post-retirement corpus.

The proposed APY differs from the NPS-S in two significant ways. First, the NPS-S is a defined contribution scheme where the subscriber’s contribution is invested in government securities, corporate bonds, and equity instruments-the scheme does not guarantee fixed returns to subscribers. In contrast, the APY is a defined benefit scheme that will provide the subscriber with fixed monthly incomes between Rs.1000 and Rs.5000 based on the respective monthly contribution amounts (which varies by age and saving potential of the subscriber; refer Table 2 below). Second, under the APY, the government will match either 50 per cent of the subscriber’s contribution or Rs. 1000, whichever is lower (initially for a five year period till 2019-20). This paves the way for the creation of a graded matching scheme where subscribers who contribute below Rs. 1000 also receive a (less than equal) matching contribution. For availing the same amount of co-contribution as under the NPS-S, a subscriber will need to contribute Rs. 2000 into APY (Rs. 1000 under NPS-S).

Adequacy of benefit

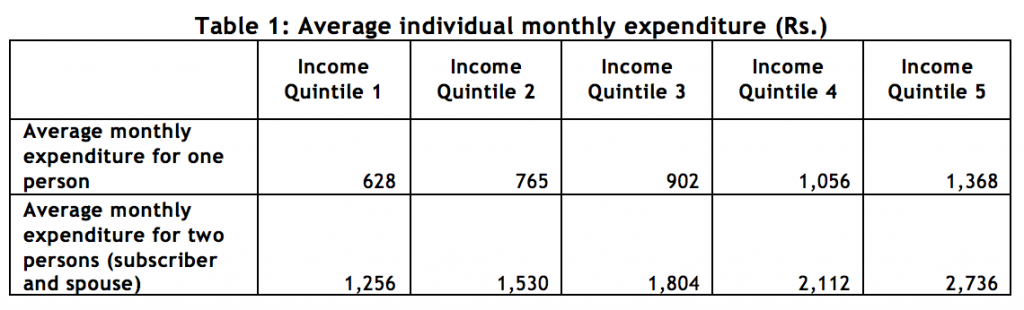

In order to judge the adequacy of the defined benefit proposed under APY, we compare the proposed benefit to the average monthly expenditure incurred by individuals in the lowest income quintile. Table 1 below presents the average monthly expenditure of an individual in each income quintileii. As the Table shows, the average monthly expenditure of an individual in the first income quintile is Rs. 628. As the APY is designed as a pension scheme for a household, we assume the average monthly expenditure for two people in our analysis.

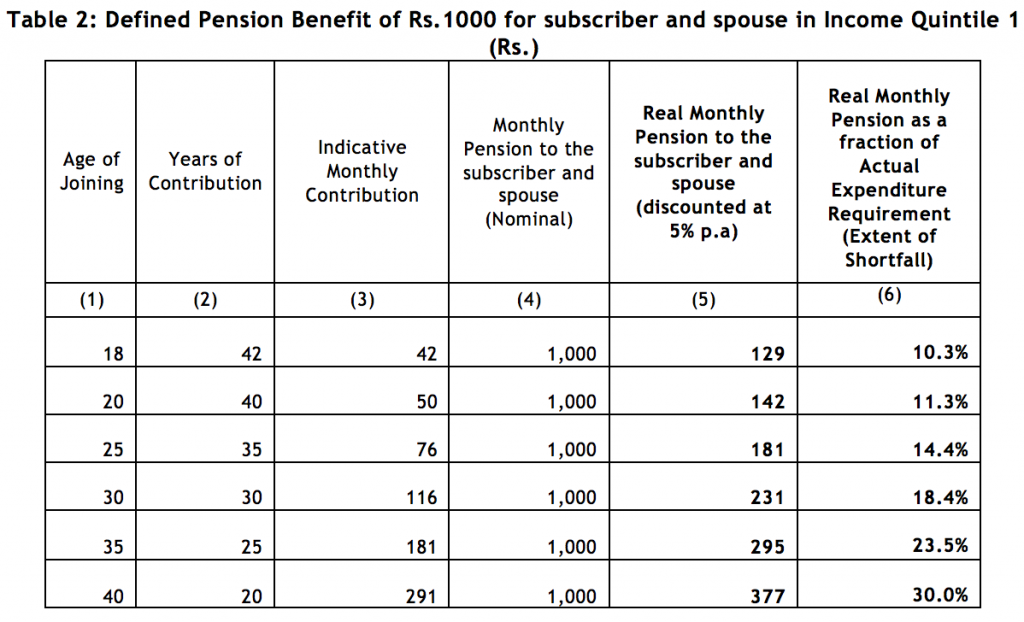

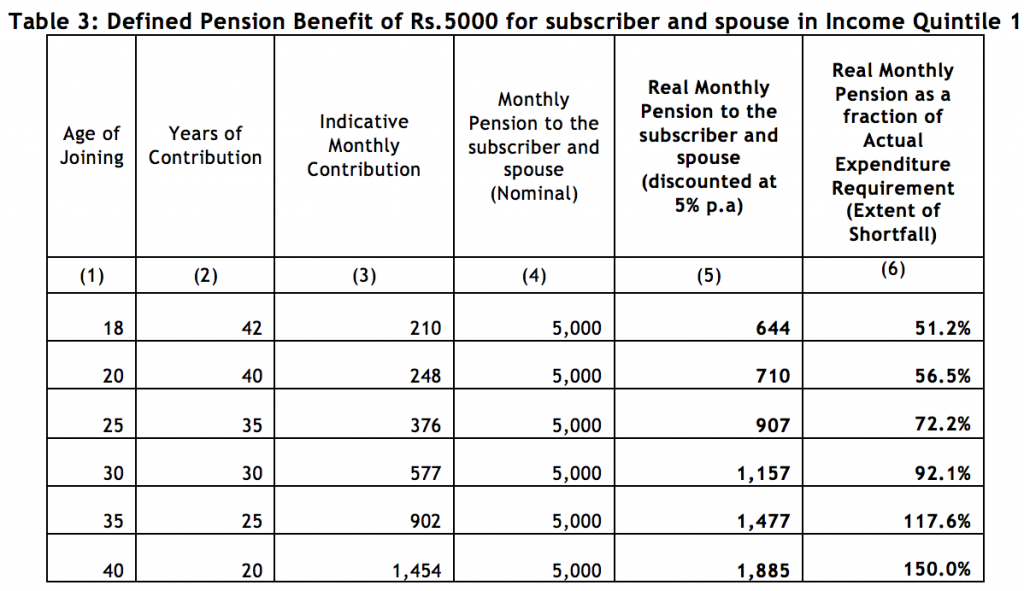

Table 2 and Table 3 (below) present the defined pension amount (nominal and real) that will be paid to the subscriber and his spouse based on two sets of indicative monthly contributions so as to get nominal defined benefit pay-outs of Rs. 1,000 per month and Rs. 5,000 per month respectively. For example, in order to receive a nominal defined benefit of Rs. 1000 per month at the time of retirement at 60 years (Table 2, Column 4), an 18-year old needs to contribute Rs. 42 per month while a 40-year old needs to contribute Rs. 291 per month. Similarly, in order to receive a nominal defined benefit of Rs. 5000 per month (Table 3, Column 4), an 18-year old and a 40-year old need to contribute Rs. 210 per month and Rs. 902 per month respectively.

Source: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=116208 and author’s own calculations.

Table 2 and Table 3 also provide, in Columns 5 and 6, the real monthly pensions that households would receive and the shortfall in pension compared to their expenditure needs, which is a more realistic representation of the actual value of money households will actually be able to get. In order to calculate the real value of the pension we present value the cash flows at a discount rate of 5%, which is one per cent higher than the long-term inflation target, set by the Reserve Bank of India. According to the indicative tables, an 18-year old who contributes Rs. 42 per month will result in a real monthly pension of of Rs. 129 for the household. Assuming that the 18-year old’s income falls within the first income quintile, the defined benefit will cover 10.3% of her monthly expenditure. However, even if the 18-year is able to contribute Rs. 210 per month towards pensions, the defined benefit at retirement will yield a real monthly amount of Rs. 644 for the household (equivalent to a nominal monthly pension of Rs. 5,000) and will be sufficient to cover only 51.2% of her monthly expenditure.

Thus, an 18-year old in the first income quintile can hope to cover between 10% and 51% of her monthly expenditure upon retirement by contributing to the scheme. Tables 2 and 3 also make clear that there is a real risk of significant shortfalls for all age-groups, whether they contribute into the nominal defined benefit of Rs. 1,000 or Rs. 5,000.

It should also be noted that if inflation continues to hover around historical inflation of 8%, the defined benefit would cover a much lesser percentage of an individual’s expenditure per annum. For instance, for an 18-year old who contributes Rs. 42 a month, the monthly defined benefit would be sufficient to cover a mere 3.1% of her monthly expenditure upon retirement.

The need for inflation indexation and a more optimal investment mix

If we assume that the government contribution will be discontinued at the end of five years, the annualised rate of return required to guarantee Rs.1000 per month (or Rs.1.7 lakh corpus) for an 18-year old contributing Rs. 42 a month is 7.58%. If we relax the assumption that government contribution will be discontinued and that the matching contribution from the government will continue in perpetuity, the annualised rate of return required to guarantee the defined benefit drops to 6.68%. Depending on the evolution of inflation rates over time, these nominal rates of return could end up resulting in very low real return or even the risk of erosion in capital due to inflation. The APY could benefit from addressing two key design limitations of the NPS-S:

- Lack of inflation indexation: In order to ensure that the pension corpus of low-income customers is not eroded over time, the government needs to index both the subscriber contribution and the matching contribution to inflation. Assuming that the matching contribution continues in perpetuity and that the government invests the corpus in the current NPS-S investment mix (upto 85% in government bonds and upto 15% in equity), indexing both the subscriber and government contributions to inflation on an annual basis could provide the subscriber with a substantially higher corpus (as much as 4 times higher than the guaranteed amount). Indexing social security benefits to inflation would also be in line with international best practices. For instance, the US Social Security Administration makes an annual cost of living adjustment by linking social security benefits to the Consumer Price Index.

- Conservative investment mix: The current NPS-S investment mix invests upto 85% of the corpus in bonds and upto 15% in equity, the remaining comprising of corporate bonds. In contrast, the NPS-Main follows a life-cycle investment mix which invests 50% of a 20-year old subscriber’s corpus in equity, 30% in corporate bonds, and 20% in government bonds. As the subscriber ages, the share of equity and corporate bonds is reduced and transferred to the less-volatile government bonds. According to our calculations, investing in the life cycle fund mix could provide returns that are 49% higher than the returns on the current NPS-S mix. While guaranteeing a minimum amount through investments in approved fixed income instruments, the government could ensure that subscribers can accumulate corpuses that vastly exceed the guaranteed benefit by shifting to a more equity-heavy investment mix depending on age of the subscriber.

It is indeed heartening that there is a lot of policy attention on these very important questions of old age income security, and the emergence of the NPS and now the APY are testament to this. If some of the design limitations of the NPS-S were to be addressed in the APY, it would mean that the most vulnerable households would be able to build pension corpuses that could meaningfully provide them with old age income security.

—-

– http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=116208

– This analysis has been performed on data from a financial services firm that is operational across rural districts in three states of India for a sample of over 200,000 households.

6 Responses

Should we think about giving the already announced DB benefit as a base pension and then allow the NPS-S benefits to accrue?

Agreed Monika. It makes a lot more sense to have a universal minimum pension at the level of the national poverty line, which according to the Rangarajan Committee Report is in the region of Rs. 1,100 per month. Above and beyond this, subscribers should be voluntarily saving through the NPS-S scheme to secure their requisite pension corpus. We are putting together a working paper on a national pensions framework, which will also elaborate on these themes and will be out shortly.

After 42 years of contribution you will get 5000 and after 42 years 5000 means equal to 710 to 800 as per the inflation calculation for next 42 years.

I simply don’t understand! Whether it is for the lower sector or not it is a bad scheme. If the same amount is put monthly in a recurring deposit or even in a fixed deposit at the end of every year, for example, 291 a month for a 40 year old for 20 years at the current interest rates it will be close to 2 lacs. This will fetch an interest of about 1,350 per month after TDS which is far better than the 1000 a month pension one would get. Additionally, your 2 lacs will remain in the fixed deposit from that point onwards.

Thank you for sharing this analysis. This is very helpful.

Growing the pension year on year can mean that the liability for the Government will keep on increasing which may not be liked by them.