Digital payments are growing rapidly in India, with the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) system emerging as the main driver of this growth. However, there is much left to be desired. The Payments Vision 2025 Document of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) acknowledges that inclusion of first-time users is affected by challenges relating to onboarding, retention, improving convenience and providing tailored payment solutions to users.[1] This raises the following questions – who are the users experiencing friction in the digital payments journey, and how can the design of digital payments reduce that friction?

In India, a lack of official disaggregated data (by income, gender, population group etc.) on users makes it difficult to identify how the growth in the adoption of digital payments is spread among India’s population.[2] This, in turn, makes it difficult to determine who is lagging in using payments and the reasons for it.

This post explores literature from India and other jurisdictions to gain conceptual knowledge about the kind of users that face friction in adopting and using digital payments, and the principles and practices that can improve the usability of payment applications. We hope this synthesis will motivate further discussion on (a) identifying the challenges different users in India face along the user journey of digital payments, and (b) designing safe payments applications that match the skills and realities of users, especially those who are new to the digital ecosystem.

- Who are the users’ facing challenges in using digital payments?

First, we summarise our findings from literature on the users who face constraints in using digital payments. We find that the constraints users face can predominantly be attributed to the digital divide i.e., the gap in access to necessary infrastructure and digital skills between different kinds of users. The digital divide itself seems to mostly be moderated by socio-demographic factors like users’ gender, age, literacy, education, income, occupation, disabilities, and geography.[3] We find that–

- Historically marginalised groups face constraints in using digital payments:

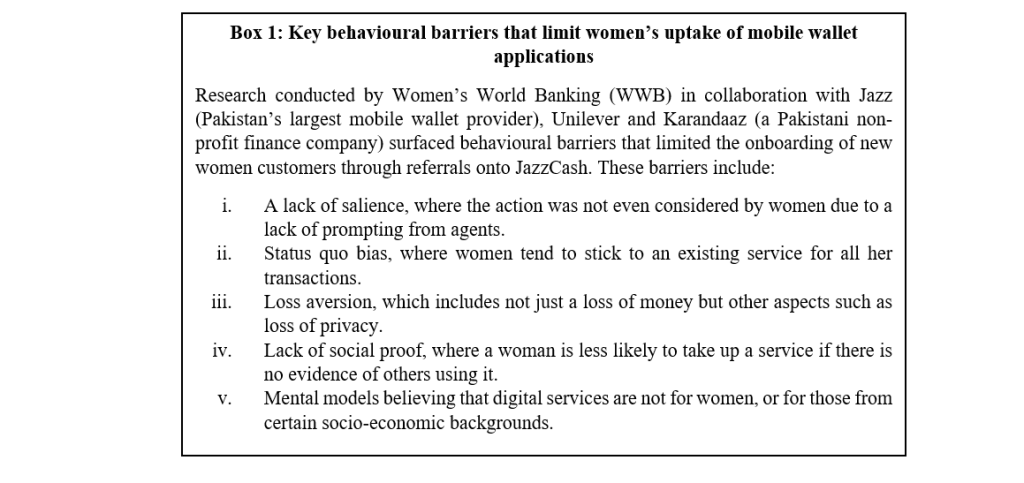

The access to and use of digital interfaces appears closely related to the historical socio-economic position of the user. For instance, women are less likely than men to own a mobile phone, or an internet connection that can support digital payments.[4] Women may often be less literate and less educated, which could further limit their ability to use digital payments.[5] Women may also be discouraged by socio-cultural norms that influence their access to and use of mobile phones.[6] Further, when women experience a lack of agency over using financial services, it can affect their use of digital payments, mainly in rural areas.[i] For instance, limited influence over major spending decisions, rigid rules about what is perceived as acceptable and safe for women, lack of narratives about women as financial contributors, and perceptions about digital financial services being complex, are some factors that could distance women from digital payments.[7] Relevant insights from a study in Pakistan are presented in Box 1.[8] It appears that these barriers can be attributed to the socio-economic stature of women in the society and it is likely that other users, who may not be women but are similarly located in society could also face these barriers.[9]

- Geographical barriers limit access to necessary ICT devices and services:

Users living in semi-urban and rural geographies may have poor access to smartphones, internet connection, electricity and other important services that support payments. These users may also lack access to digital access points like bank branches, ATMs and merchants accepting payments.[10]

- Digital payments may be prohibitively expensive for low-income users:

Low-income users tend to more often be unbanked, lack access to formal financial services, and have irregular income.[11] These users may be less likely to use payments because of the costs involved in purchasing necessary devices and accessing the internet.[12] Their limited financial capability also amplifies the fear of loss, where any loss would outweigh the benefits provided by digital services.[13]

- Users with limited digital and general literacy can find navigating payment applications difficult:

These users could find payment application interfaces complex and non-intuitive. These challenges can be compounded for users with cognitive and visual disabilities.[14]

- Bad experiences can distance users from digital payments:

The challenges that constrained user segments face could be further accentuated by their past experiences of digital financial services. Experiencing harms through frauds or privacy breaches directly, or knowing about them through somebody else, could create mistrust and discourage users from using payments services.[15] This behaviour correlates with a prior low level of trust in the financial services/sector, and with lack of financial literacy and awareness.[16]

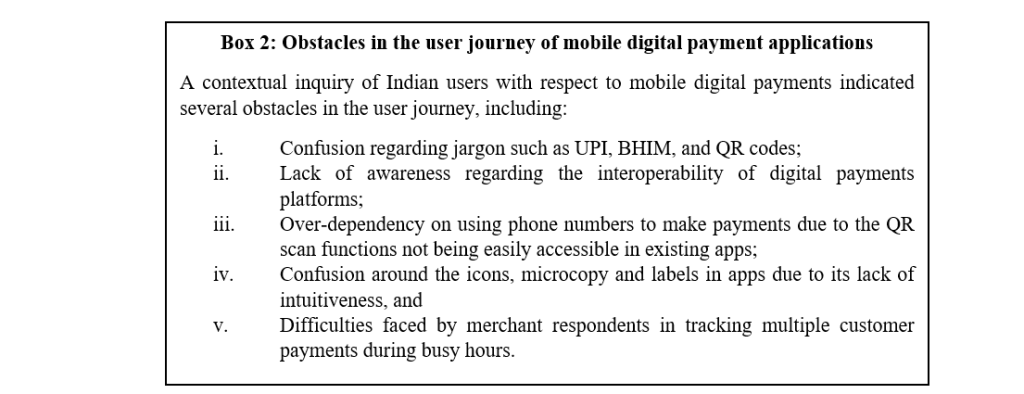

Insights from an exploratory research study in India which conducted an in-person contextual enquiry on the obstacles faced by 12 users in using mobile digital payment applications are presented in Box 2.[17]

2. What are the design principles and best practices to help address usability challenges?

Next, we summarise our findings from the literature on the principles that enhance the usability of applications and make them accessible for users. While some of the barriers that users face can only be mitigated through infrastructural interventions, design interventions in the user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) of payment applications can help mitigate others.[18] The digital divide includes three components: an economic divide, an empowerment divide, and a usability divide. Although design interventions cannot address the economic divide, they can improve usability and narrow the empowerment divide.[19] Therefore, good design can determine if a user uses a digital financial service.[20]

An expert review of select app-based financial services in India by Raman and White (2017) identified usability problems from the perspective of first-time smartphone users and low-income segments.[21] The review looked at the potential usability issues with respect to various aspects of the app such as navigation, comprehension, language, inputting data, moving between steps, errors, confirmations, exploration, registration, and assistance. It indicated that every decision point on every screen of the application could be a point of friction for a user. As such, every aspect of design must be oriented towards increasing and reinforcing the confidence of a user.[22]

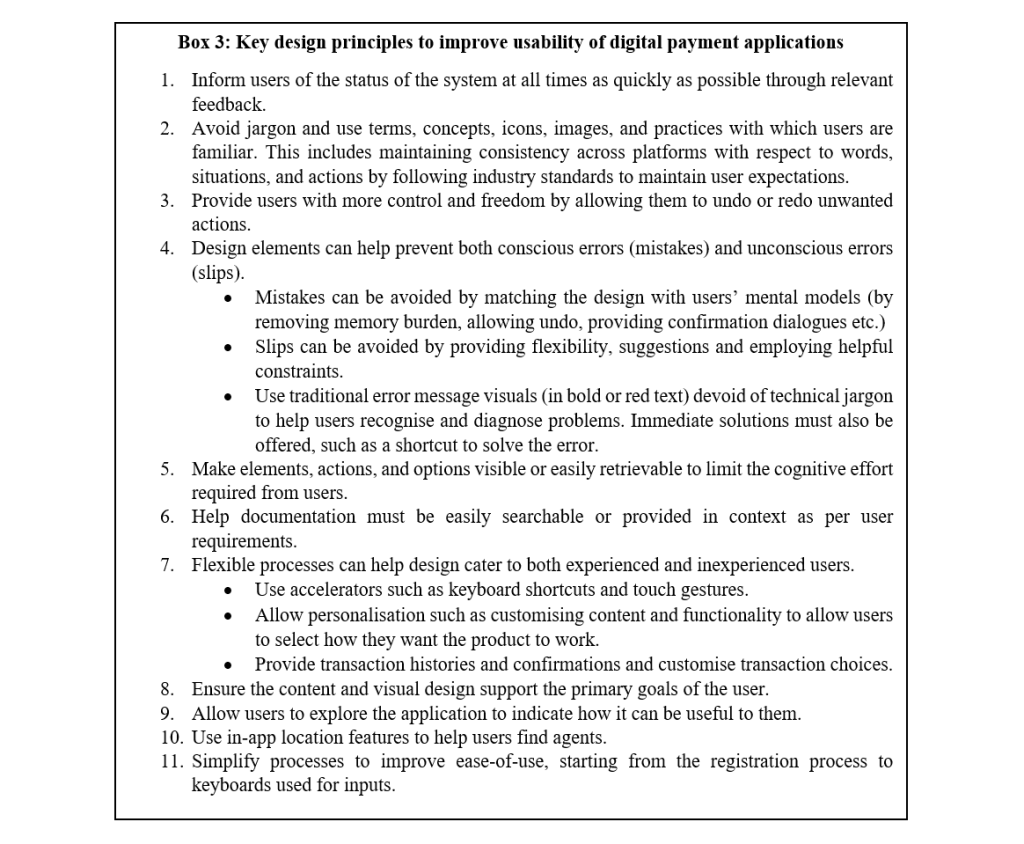

Recommendations across studies in our literature review broadly adhered to Jakob Nielsen’s “10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design”. These principles are broad rules of thumb relating to interaction design but are not specific guidelines.[23] The principles have also been customised in various studies for designing mobile money service interfaces on smartphones for mass usage in low-income countries. In these cases, the principles apply to basic mobile money functions such as learning about and exploring the service, registering on an application and beginning to use it, depositing/withdrawing money, and making basic payments.[24] Service providers (such as Google) also conducted studies to help improve mobile application design to engage users and drive conversions. The insights from these studies pointed towards a checklist of principles to be applied across 6 categories or functions of app use to help improve design. These functions include: (i) Application navigation and exploration; (ii) In-App search; (iii) Commerce and conversions; (iv) Registration; (v) Form entry; and (vi) Usability and comprehension.[25]

The key underlying principles from various studies are collated in Box 3.[26]

Our review shows that the most constrained users are those with lower access to technology, lower digital literacy, and those who are more vulnerable to financial losses or harms. Devising solutions to mitigate these barriers needs an in-depth understanding of the user’s requirements. This requires –

-

Studies to be undertaken to meet the users where they are to understand their specific needs, and

- Capturing and segmenting data for conducting specific user testing to serve the different needs of different population segments.

These insights can serve as the foundation to improve the design elements of applications which will enhance usability, and ultimately build confidence and trust for a user in the digital payments journey.

[i] The study by IDEO and BMGF was conducted in rural areas of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Northern Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania.

[1] Reserve Bank of India. (2022). Payments Vision 2025. Retrieved from *PAYMENTSVISION2025844D11300C884DC4ACB8E56B7348F4D4.PDF (rbi.org.in).

[2] Buteau, S., Rao, P., & Valenti, F. (2021). Emerging Insights from Digital Solutions in Financial Inclusion. CSI Transactions on ICT, 9, 105-114. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40012-021-00330-x

[3] Shree, S., Pratap, B., Saroy, R., & Dhal, S. (2021, January). Digital payments and consumer experience in India: A survey based empirical study. Journal of Banking and Financial Technology, 5, 1-20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s42786-020-00024-z; International Finance Corporation. (2017). A Sense of Inclusion: An Ethnographic Study of the Perceptions and Attitudes to Digital Financial Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved from International Finance Corporation: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/81049b34-6f4b 4aaf-a675 59986ab8adf9/IFC+A+sense+of+Inclusion+DFS+Ethnographic+Study+2017.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=m0Ie96b; Manzar, O., Kumar, R., Mukherjee, E., & Aggarwal, R. (2020, August). Exclusion from Digital Infrastructure and Access. Retrieved from Centre for Equity Studies: http://centreforequitystudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/3-Exclusion-from-Digital-Infrastructure-and-Access.pdf.

[4] Sonne, L. (2020, August). What do we know about women’s mobile phone access and use? A review of evidence. Retrieved from Dvara Research: https://dvararesearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/What-Do-We-Know-About-Womens-Mobile-Phone-Access-Use-A-review-of-evidence.pdf; Barboni, G., Field, E., Pande, R., Rigol, N., Schaner, S., & Moore, C. T. (2018). A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India. Retrieved from Harvard Kennedy School: Women and Public Policy Program: https://wappp.hks.harvard.edu/publications/tough-call-understanding-barriers-and-impacts-womens-mobile-phone-adoption-india.

[5] OECD. (2018). Bridging the digital gender divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate. Retrieved from OECD: https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf.

[6] Women’s World Banking. (2019). Acquisition and Engagement Strategies to Reach Women with Digital Financial Services. Retrieved from Women’s World Banking: http://womenswb.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Aquisition-Engagement-Strategies_WomensWorldBanking.pdf; Sonne, L. (2020, August). What do we know about women’s mobile phone access and use? A review of evidence. Retrieved from Dvara Research: https://dvararesearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/What-Do-We-Know-About-Womens-Mobile-Phone-Access-Use-A-review-of-evidence.pdf; Barboni, G., Field, E., Pande, R., Rigol, N., Schaner, S., & Moore, C. T. (2018). A Tough Call: Understanding barriers to and impacts of women’s mobile phone adoption in India. Retrieved from Harvard Kennedy School: Women and Public Policy Program: https://wappp.hks.harvard.edu/publications/tough-call-understanding-barriers-and-impacts-womens-mobile-phone-adoption-india; Bailur, S., Smertnik, H., Shulist, J., Katakam, A., & Kendall, J. (2020, December 22). Moving Beyond Access to Design: The relevance of the Level One Principles for the gender DFS gap. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3773132.

[7] IDEO.org. (2021). Women & Money: Insights and a Path to Close the Gender Gap. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d94e54cb06c703e5199d288/t/60c931ef54473e6b91ae8e1b/1623798282681/Women_Money_FinalReport_2021.pdf.

[8] Women’s World Banking. (2019). Acquisition and Engagement Strategies to Reach Women with Digital Financial Services. Retrieved from Women’s World Banking: http://womenswb.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Aquisition-Engagement-Strategies_WomensWorldBanking.pdf.

[9] Rajam, V., Reddy, A.B., Banerjee, S., Explaining caste-based digital divide in India, TELEMATICS AND INFORMATICS 65 2021, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0736585321001581.

[10] GSMA. (2021). The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity. Retrieved from GSMA: https://data.gsmaintelligence.com/api-web/v2/research-file-download?id=65765378&file=280921-state-of-mobile-internet-connectivity-2021.pdf; Kulkarni, A., & Gupta, S. (n.d.). Users’ Perspectives on Digital Payments. Retrieved from CUTS International: https://cuts-ccier.org/pdf/Presentation_for_RBI_Committee_on_Deepening_Digital_Payments.pdf; Women’s World Banking. (2019). Acquisition and Engagement Strategies to Reach Women with Digital Financial Services. Retrieved from Women’s World Banking: http://womenswb.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Aquisition-Engagement-Strategies_WomensWorldBanking.pdf.

[11] Saxena, R., & Punekar, R. (2021). The Factors Influencing Usage Intention of Urban Poor Population in India towards Mobile Financial Services (Mobile Payment/Money). Part of the Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies book series (SIST, volume 222); Conference Paper 2021. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-0119-4_6.

[12] Henrique de Araujo, M., & Diniz, E. (2021, May). Understanding the use of digital payments in Brazil: An analysis from the perspective of digital divide measures. Retrieved from ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352156935_Understanding_the_use_of_digital_payments_in_Brazil_An_analysis_from_the_perspective_of_digital_divide_measures; Shree, S., Pratap, B., Saroy, R., & Dhal, S. (2021, January). Digital payments and consumer experience in India: A survey based empirical study. Journal of Banking and Financial Technology, 5, 1-20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s42786-020-00024-z.

[13] Ibtasam, S., Razaq, L., Anwar, H., Mehmood, H., Shah, K., Webster, J., . . . Anderson, R. (2018). Knowledge, Access, and Decision-Making: Women’s Financial Inclusion In Pakistan. COMPASS ’18: ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (COMPASS). Retrieved from https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3209811.3209819.

[14] James, J. (2019). Confronting the scarcity of digital skills among the poor in developing countries. Development Policy Review. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dpr.12479; Raman, A., & White, G. (2017, March). Financial Services Apps in India: How to improve the user experience. Retrieved from CGAP: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/slidedeck/Financial-Services-Apps-in-India-Mar-2017.pdf; Rana, N. P., Luthra, S., & Rao, H. R. (2019). Key challenges to digital financial services in emerging economies: the Indian context. Information Technology & People, 33(1), 198-229. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-05-2018-0243; Kameswaran, V., & Muralidhar, S. H. (2019, November). Cash, Digital Payments and Accessibility – A Case Study from India. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact., 3, 23. Retrieved from https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3359199.

[15] Singh, J. B., & Vimalkimar, M. (2019, August). From Mobile Access to Use: Evidence of Feature-level Digital Divides in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(32). Retrieved from https://www.epw.in/journal/2019/32/special-articles/mobile-access-use.html; Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012, March). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157-178. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41410412#:~:text=the%20consumer%20technology%20industry%20better,stages%20of%20the%20use%20curve.&text=extend%20UTAUT%20(i.e.%2C%20hedonic%20motivation,and%20habit)%20to%20formulate%20UTAUT2.&text=to%20the%20consumer%20technol; Gupta, K. P., Manrai, R., & Goel, U. (2019, February). Factors influencing adoption of payments banks by Indian r

rs: Extending UTAUT with perceived credibility”. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 13(2). Retrieved from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JABS-07-2017-0111/full/html?skipTracking=true.

[16] International Finance Corporation. (2017). A Sense of Inclusion: An Ethnographic Study of the Perceptions and Attitudes to Digital Financial Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved from International Finance Corporation: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/81049b34-6f4b-4aaf-a675-59986ab8adf9/IFC+A+sense+of+Inclusion+DFS+Ethnographic+Study+2017.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=m0Ie96b.

[17] Chheda, Y. (n.d.). Exploratory Study on Digital Payments in India. Retrieved from Yash Chheda: https://yashchheda.webflow.io/work/research-study-digital-payments-india

[18] Raman, A., & White, G. (2017, March). Financial Services Apps in India: How to Improve the User Experience. CGAP. Retrieved from https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/slidedeck/Financial-Services-Apps-in-India-Mar-2017.pdf.

[19] Joglekar, B. (2019, May). Paisy: A Mobile Banking Experience for Indians with Limited Digital Literacy. Retrieved from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/78204/JOGLEKAR-MASTERSREPORT-2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[20] CGAP. (2022). Informed Design: A Case Study Series Insights from WomenSave. FinEquity. Retrieved from https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publications/2022/FinEquity_WomenSave_CaseStudy_FINAL.pdf.

[21] Raman, A., & White, G. (2017, March). Financial Services Apps in India: How to Improve the User Experience. CGAP. Retrieved from https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/slidedeck/Financial-Services-Apps-in-India-Mar-2017.pdf.

[22] Raman, A., & White, G. (2017, March). Financial Services Apps in India: How to Improve the User Experience. CGAP. Retrieved from https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/slidedeck/Financial-Services-Apps-in-India-Mar-2017.pdf.

[23] Nielsen, J. (1994, April 24). 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design. Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/.

[24] Chen, G., Fiorillo, A., & Hanouch, M. (2016, October). Smartphones & Mobile Money: Principles for UI/UX Design (1.0). CGAP. Retrieved from https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/slidedeck/principlesofsmartphonedesign05oct16-161005230428.pdf.

[25] Gove, J. (2016). Principles of Mobile App Design: Engage Users and Drive Conversions. Google. Retrieved from https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/_qs/documents/23/principles-of-mobile-app-design-engage-users-and-drive-conversions.pdf.

[26] Chen, G., Fiorillo, A., & Hanouch, M. (2016, October). Smartphones & Mobile Money: Principles for UI/UX Design (1.0). CGAP. Retrieved from https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/publications/slidedeck/principlesofsmartphonedesign05oct16-161005230428.pdf; Gove, J. (2016). Principles of Mobile App Design: Engage Users and Drive Conversions. Google. Retrieved from https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/_qs/documents/23/principles-of-mobile-app-design-engage-users-and-drive-conversions.pdf; Nielsen, J. (1994, April 24). 10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design. Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/.

Cite this blog:

APA

Stanley, S., & Prasad, S. (2022). Towards designing UPI services for constrained users. Retrieved from Dvara Research.

MLA

Stanley, Sarah and Srikara Prasad. “Towards designing UPI services for constrained users.” 2022. Dvara Research.

Chicago

Stanley, Sarah, and Srikara Prasad. 2022. “Towards designing UPI services for constrained users.” Dvara Research.