In this ongoing series, we will cover stories of citizens who have been excluded from social protection benefits delivered through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and Public Distribution System (PDS). In collaboration with Gram Vaani*, a grassroots-level social tech company, we document the stories of beneficiaries who have faced challenges in welfare access in M.P., Bihar, U.P., and Tamil Nadu.

The following case study highlights how document requirements and the subsequent lack of clear information/instructions at enrolment points can be an impediment for citizens seeking food grain support from the Public Distribution System (PDS). The linking of identity systems (in this case, Aadhaar) with social protection potentially complicates obtaining benefits, especially when there is no scope to use alternate documents as identity proof. The preclusion of exception management protocols contributes to the exclusion of eligible beneficiaries. The inability to communicate correct resolution pathways to citizens at enrolment points is a direct result of application processing systems not being equipped to provide reasons for rejection of an application. This only compounds the access problem further. The compounding of exclusion primarily occurs when welfare schemes are designed in a siloed manner, independent of one another. For instance, enrolment into one scheme may be a pre-requisite to receive unrelated benefits from another. The case study in question describes exclusion from the PDS leading to further exclusion from COVID-19 relief efforts targeted at ration cardholders and other social services as well.

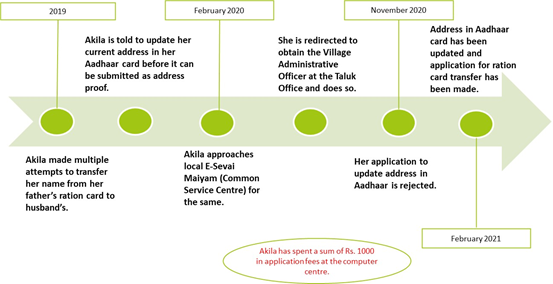

Akila (name changed) got married three years ago, and for the past year, she has been attempting to transfer her name from her father’s ration card to her husband’s. She was asked to produce her Aadhaar card to check that the address on her Aadhaar card matched with the address on her husband’s ration card. Gram Vaani volunteers confirm that verifying the address on the Aadhaar card matches that of the ration card is a requirement in Tamil Nadu.[1] Since Akila’s Aadhaar card reflected her previous address (as before marriage), she first had to update the address details in her Aadhaar card. It is from this stage that her exclusion originates. Akila has approached the local E-Sevai Maiyam (equivalent to a Common Service Centre (CSC)) multiple times to change her address on her Aadhaar card, with no success. The CSC operators redirected her to the taluk office to obtain the signature of the Village Administrative Officer (VAO), which she promptly did. Even after submitting the signed letter and new address to the E-Sevai Maiyam, her application to update her details was rejected. This cycle of application and submission of documents has occurred twice since February 2020. In November 2020, Akila was told that she required the signature of a Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) in order to process her address change request.

Akila’s attempts to update her Aadhaar card has also cost her monetarily – she had to spend a total of Rs. 1000 (approximately) in application and re-application fees at the CSC. Her multiple visits to the CSC imply time and effort lost as well. She has not been provided with a reason for the rejection of her application and is at a loss regarding how she must proceed to correct her Aadhaar details and ultimately obtain her ration card. The inability to update the Aadhaar card presents the first level of exclusion: where a difficulty in document procurement excludes her from obtaining a ration card. The lack of a ration card further excluded Akila from a slew of other COVID-19 related relief measures: the distribution of free grain to ration cardholders under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKY), the Rs. 1000 cash transfer to ration cardholders by the Tamil Nadu State government and the increased quantity of entitlements as per the Centre and the Tamil Nadu State government. This indicates the importance of a ration card as not only the proof of enrolment into the Public Distribution System, but as a targeting method for various other schemes as well. Finally, she is facing challenges in enrolling her son into school without her name on the family ration card.

Figure 1: Timeline of Exclusion and Costs Incurred

Akila had spent nearly a year waiting on what is supposed to be a simple and straightforward process. As of February 2021, the address on her Aadhaar card has finally been updated to reflect her current residence. She has since been able to make the application which would append her name to her husband’s ration card, and is waiting for the same to be processed. The UIDAI has made infrastructure available for residents to track the status of their applications and has also set up contact centres and chatbots to help address grievances. However, in this case, the portal to track applications offered no reason for the rejection of the request to update the address.

These cases highlight the need for a unified grievance redressal process, especially to help beneficiaries of welfare programs gain meaningful support. While the processes set up may be working perfectly for many people using the system, the cases of exclusion that do arise prompt the need for meaningful investment in building an inclusive system to allow citizens (especially welfare beneficiaries) to register and seek redressal by themselves or by well-supervised, well-incentivised structures for assistance. Since the welfare system has been structured with a singular reliance on the Aadhaar system for address verification, there is a need to ensure a degree of interoperability between the two. Without sufficient coordination between individual welfare schemes (such as the PDS) and the UIDAI-enabled Aadhaar system, individuals such as Akila will be excluded from timely and appropriate social protection.

This case study, and several others in the series, reveal citizens’ preference for assistance to navigate the administrative architecture to access welfare programs. While systems may be quite efficient and technologically novel, there is a layer of intermediation often required for beneficiaries to access benefits due to them.

A working framework to study exclusion in social protection has been employed to analyse this case, mapping points of exclusion across the four key stages of scheme design and delivery as detailed here.

*The author would like to thank Aaditeshwar Seth, Lamuel Enoch, Bruno Richardson and Eswaramoorthy from Gram Vaani for facilitating these case studies. The author would also like to thank Nishanth Kumar, Head of Research Analytics and the Social Protection Initiative for his valuable inputs in writing this case study.

[1] This was communicated to us by the Gram Vaani field operations team upon enquiry.