Olympia A. De Castro from IFMR Capital gave us an insight on the correspondent banking model in Brazil that led to some interesting comparison debates with the Indian model. We bring you some highlights of the discussion:

The Growth

According to the Central Bank of Brazil, Correspondent Banking (CB) is “a measure aimed at extending services to bank clients in areas where that bank did not have a branch”. Introduced in the 1970s, the correspondent banking channel has risen in relevance, especially after 1999 when regulatory changes broadened the range of services that could be offered by correspondent banking agents.

As the fifth largest country in the world with a population of 201 million, Brazil has correspondents covering 62 percent of the total number of points of service of the financial system. All of the 5,564 municipalities in Brazil are now reached by the channel, with 25% of the municipalities being served only by correspondents. Between 2000 and 2008, the correspondent banking system grew 85.5 percent while bank branches grew only 16.7 percent, clearly indicating the increasing presence of the channel.

Market Dynamics and Regulation – Aligned Incentives

The significant growth seen in correspondent banking industry in Brazil can be attributed to a unique market dynamic that created aligned incentives between the major stakeholders of the finance industry. In essence, the government, the central bank and the commercial banks were in different ways motivated to allow the correspondent banking model to flourish.

In 2003, Brazil’s newly elected Worker’s Party government needed an effective distribution channel to disburse its social welfare program, Bolsa Familia. The program at that point already reached 68 million benefits, equivalent to R$2.4billion. Transparent and efficient disbursement of this significant government cash transfer program was essential to its success. As of 2009, 1 in 4 households in Brazil receive a monthly G2P i.e. government to person payment. At the same time, the EIU Microscope Report released in 2008 to assess the environment for microfinance in Latin America ranked Brazil at a meagre 14 out of 20. In response to this, the Brazilian Central Bank (BCB) launched a financial inclusion program to improve financial access in the country. As a result, Brazil has seen an improvement of two points due to better regulatory capacity in the most recent 2009 Microscope report where it ranks 24 out of 55 (India was ranked 4).

Similarly commercial banks were in a position to benefit from exploring correspondent banking as a noteworthy business model. Given the years of hyperinflation in the early 90s, banks undertook technology improvements to allow for fast transaction processing. At the same time, banks became the predominant recipients for bill payments, as the public sought quick deposit and use of their rapidly depreciating currency. The resulting considerable increase in foot traffic to branches related to payment business became a strong driver for the need to find a cost effective alternative.

In turn, since the 1990s, regulation around correspondent banking has become more agreeable stimulating significant growth in the industry. From broadening the range of institutions allowed to hire agents, to widening the gamut of services and softening the restrictions over the location of agents, regulation around correspondent banking has been flexible enough to attract strong interest in it as a viable business alternative. Commercial banks are particularly keen on exploring this alternative as it allows for regional expansion and client reach with significantly lower costs. Unlike the rigid legislation of bank-branching, correspondent agents allows for lower security expenses, relatively lax liquidity management and lower labour costs given it does not fall under the domain of the strong branch unions.

Exploring the viability

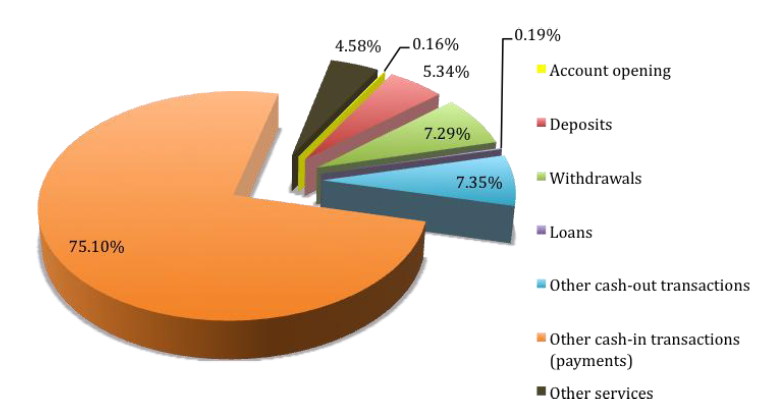

Brazilian correspondent banks are authorized to offer a wide range of products and services. However, as noted below, bill payment continues to dominate the volume of transactions.

Types of transactions conducted by correspondents

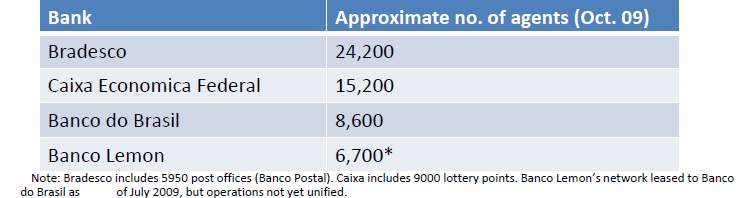

The distribution of product range varies from entity to entity as there are several types of participants in the industry. The main players are the larger banks in the country, Banco do Brasil and Caixa Economica, both wholly-owned by the government, and Bradesco, a private sector bank that entered correspondent banking by partnering with the postal service, each benefiting from the model in different ways.

Bradesco’s Banco Postal seems to be the most profitable with profit per day of US$79 versus an average of 5.2 for the others. Profit margins are also relatively higher at 63% compared to an average of 10.6% for the other agents. Contracts between agent and bank tend to vary with revenue split, capital expenditure and operational expenses being negotiated on a case by case basis.

Banco Postal’s higher margins are arguably explained by its high negotiating power. In July 2009 it effectively increased prices by 60 percent. In addition, the relatively high volume of transactions also adds to its advantages.

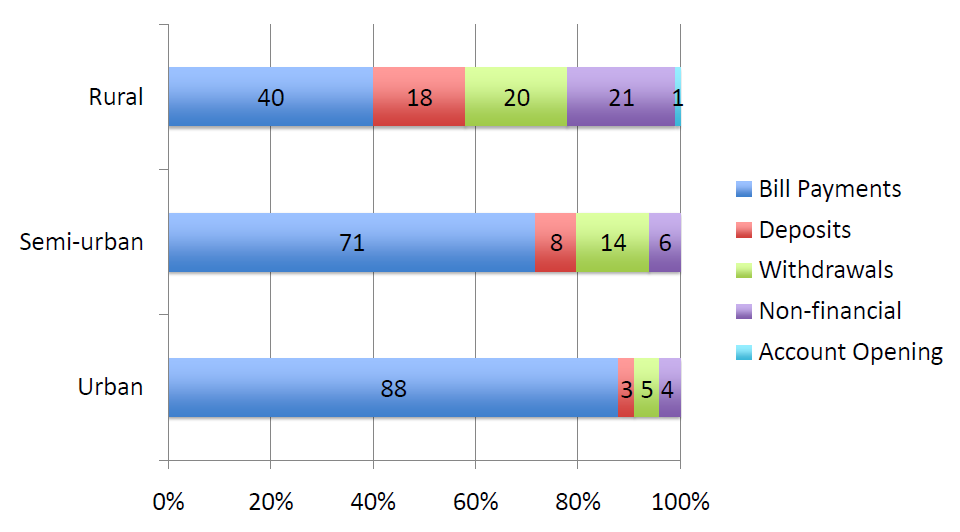

Product offering and transaction volume tend to vary by geographic region. In urban areas, bill payments are even a larger share of the number of transactions representing as much as 88 percent of total transactions. Profitability attributed to this product relies on fast rotation of clients and high foot traffic. The below chart shows type of transaction by region:

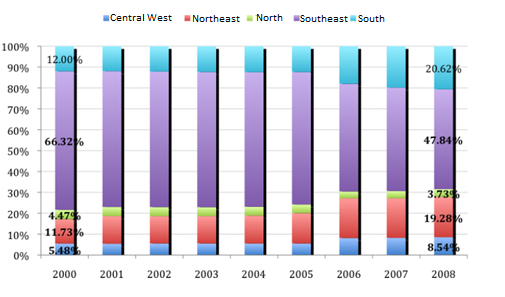

Evidently, customers in different geographic regions have different needs. However, the dynamics have led to a general urban bias in the expansion of correspondent banking. A snapshot of Brazil’s demographics shows clear differences between the regions, with the South and Southeast region being wealthier and more populous, while the North and Northeast are poorer. Despite some slight improvement, agents tend to favour the wealthier regions of Brazil. Banco Postal especially favours the South and Southeast with roughly 43% of its client located in these regions as of 2004. On the other hand, Caixa, responsible for all Bolsa Familia withdrawal transactions, unsurprisingly shows greater presence in the North and Northeast with roughly 40% of its clients attributed to these regions.

The below chart shows the evolution of the geographic concentration of correspondent banks by region:

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for the industry lie in the fact that the Central Bank of Brazil has an unclear mandate under law to regulate outsourcing. Although the framework for the use of agents is based on the Central Bank’s regulations, its authority ends short of the correspondent agents. As a result Labour Law holds precedence over the Central Bank’s regulation when it comes to correspondent banking. The same applies to other regulatory entities such as the National Health Surveillance Agency which looks over pharmacies and drugstores. As a result, several issues currently threaten the industry, as they pose risks of unviably higher costs and significant disruption in the current agent channels. Specifically, these threats include legal actions from agent employees and branch-bank labour unions demanding higher pay for agents as well as challenges raised on whether pharmacies and drugstores should engage in correspondent banking; currently pharmacies and drugstores account for ~10% of total agents.

Challenges and lessons

When considering if complete financial access is being addressed via the correspondent banking model, it is evident that several challenges remain. First, although Brazil is proud to claim presence of an agent in every municipality, this is still not sufficient as the distance between an agent and a customer in the same municipality many times is too great. Secondly, service offering continues to be dominated by bill payments. Other services such as account opening remains relatively unsuccessful; although incentives have been created for an increase in new accounts a large number of these remain inactive. In addition, credit, a core factor for financial inclusion, remains at a standstill as the right model is yet to be determined. Finally, geographic coverage based on population needs remains limited with a significant urban bias perhaps driven by relatively more attractive profitability.

Conclusions

The corresponding banking system in Brazil has a lot that can be compared to the Indian model. Despite the differences in demographics, there are several points for discussion such as what makes for a conducive regulatory environment, the benefits of a proper credit agency, considerations for credit origination models, potential products and agents to be explored and the technological and training support necessary for an effective and viable correspondent model.

As India refines its agent model and explores the best alternatives to address its financial needs it is worth drawing from the experiences and lessons of its Brazilian counterpart, which although the explosive growth in coverage, remains tasked with a number of challenges.

Sources of data:

1) Gallagher, Terence, “Branchless Banking – Brazil Correspondent Banking Networks”,CGAP, June 2006

2) Kumar, Anjali; Ajai Nair, Adam Parsons, Eduardo Urdapilleta. “Expanding Bank Outreach through Retail Partnerships”, World Bank Working paper N. 85, (June 2006)

3) Branchless Banking and Consumer Protection in Brazil, CGAP, 2009

4) Branchless banking agents in Brazil – Building viable networks, CGAP, 2010

2 Responses