In this ongoing series, we will cover stories of citizens who have been excluded from social protection benefits delivered through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and Public Distribution System (PDS). In collaboration with Gram Vaani*, a grassroots-level social tech company, we document the stories of beneficiaries who have faced challenges in welfare access in M.P., Bihar, U.P., and Tamil Nadu.

PM Kisan (PMK) is a Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme under the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India. Under PMK, registered farmers who own small and medium-sized landholdings, receive Rs. 6,000 per annum directly into their bank or Post Office accounts in three instalments spread throughout the year. Although new features such as online self-registration, self-correction of beneficiary records set the scheme apart from most of the other government schemes in place, legacy issues related to bureaucratic delays and process opaqueness continue to cause difficulties for prospective beneficiaries. In this case study, we explore the case of a farmer who spent a year attempting to enrol under PMK. We discuss the various delays in the process, continued discretion afforded to local functionaries, and the consequent search costs of information that beneficiaries incur in the absence of streamlined systems that fail to extend to the last-mile.

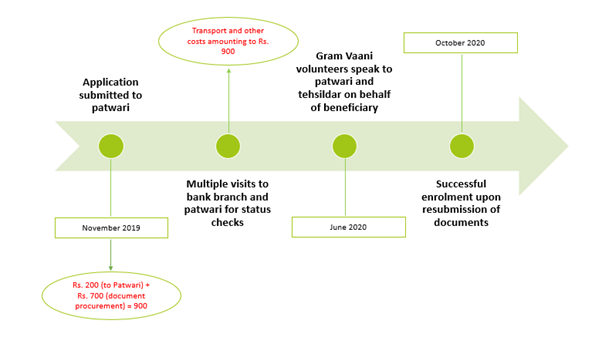

Mr. Suresh Kumar, a resident of Shivpuri, M.P., had submitted his PMK application to the local patwari[1] of his village in November 2019. Patwaris are responsible for approving PMK applications at the panchayat-level, after a thorough inspection of land records submitted by prospective beneficiaries. As part of his application, Mr. Kumar had submitted his land ownership records, bank passbook copy, and Aadhaar card copy. After having submitted these documents, Mr. Kumar waited for his instalments to arrive. Not having received any status update for months, he approached the patwari, who claimed that Mr. Kumar would be registered soon. However, as per the latter’s account, any action was yet to be taken on his application. When we spoke to Mr. Kumar in June 2020, he informed us that he does not even know whether his application has been forwarded for approval by the patwari or not. Since the application was yet to be processed by the patwari, it did not even reflect in the digitised records available on the PMK website. He also told us that the patwari was the only enrolment point for PMK in his village, and therefore, he could not approach any other point to get his application processed.

With the online status check option unavailable for such a scenario and lack of any clear communication from the patwari, Mr. Kumar was forced to make multiple trips to the nearest bank branch to check whether he has received the instalment, returning empty-handed every single time. It must be noted here that the scheme has guidelines in place to notify beneficiaries of their enrolment into the scheme; lists are to be displayed at the Panchayat offices and SMS notifications to be sent so people may immediately know of their status[2]. In Mr. Kumar’s case, since the patwari himself was not moving the application forward (for reasons unknown), none of those avenues proved useful for a status-check.

In June 2020, Gram Vaani, on behalf of Mr. Kumar, brought the matter to the notice of the local tehsildar[3], who in turn ordered the patwari to expedite the process. Gram Vaani also spoke with the concerned patwari, who claimed that he had done all that was required at his end and had submitted Mr. Singh’s applications at the local tehsil office. None of the access points (the patwari or the tehsil office) involved in the enrolment process seemed to assume responsibility for the delay in the process.

Meanwhile, Mr. Kumar continued to incur costs throughout the year. As of June 2020, he had spent approximately Rs. 1,800-2,000 in the process. This included the payment made to the patwari (Rs. 200), costs incurred while procuring necessary documentation (Rs. 700), and lastly travel costs (remaining sum), given that the bank branch and other access points were located far away from his village. An even more disconcerting fact was that after the COVID-19 lockdown, the lack of public transport had compounded the accessibility issue. People residing in remote villages were forced to rely on fellow villagers who owned private transport for the commute, to whom they then paid money/wheat grains as compensation for the fuel and amount of time spent. Mr. Kumar also had to make many such trips to the bank branch that was located 9 kilometres away from his village.

It was only in October 2020, when Mr. Kumar resubmitted his documents to the patwari, that his registration under PMK was successful. It is unclear why his application was successfully processed this time around and not when he had initially submitted it a year ago. Notwithstanding any contingent factors at play, Mr. Kumar’s case illustrates how local functionaries like the patwari continue to exercise discretion in granting access to welfare benefits even under the DBT system, an initiative designed to eliminate such factors.

Figure: Timeline of Exclusion and Costs Incurred

A working framework to study exclusion in social protection has been employed to analyse this case, mapping points of exclusion across the four key stages of scheme design and delivery as detailed here.

*The author would like to thank Aaditeshwar Seth, Sultan Ahmad, Matiur Rahman, Ashok Sharma, and the Field Operations team at Gram Vaani for facilitating these case studies.

[1] A patwari is the lowest state functionary in the Revenue Collection System and is tasked with maintaining land records and tax collection.

[2] PM Kisan Operational Guidelines – 2019. (2019). Retrieved 10 November 2020, from http://agricoop.nic.in/sites/default/files/operational_GuidePM.pdf

[3] A tehsildar is the Chief Officer-in-Charge of revenue administration of a block.

One Response

Thanks! Very informative blog.