The Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana has been envisioned to make access to inexpensive formal credit a reality for India’s enterprises. The scheme has been operationalised through a process of institution-level target setting, against which banks are to disburse unsecured enterprise loans up to Rs10 lakh. We look at the evidence on whether Mudra has had an impact on the flow of credit to micro, small and medium enterprises.

There is no single dataset that sheds light on the flow of credit to non-corporate enterprises and households engaged in non-agribusiness activities, especially because the borrower cannot be characterised by a cap on his/her extent of borrowing. However, the RBI has three relevant datasets from which we can piece together what might be happening. These are:

- outstanding banking credit data for different loan sizes,

- for priority sector lending-MSME loans,

- and for loans to the household sector; which includes loans to proprietary concerns and partnership firms, from which we can remove personal loans for consumption.

None of these datasets capture Mudra loans in their entirety. However, in combination, they provide a good picture of overall trends. Since absolute numbers are growing, we compare relative annual growth rates to tease out differences.

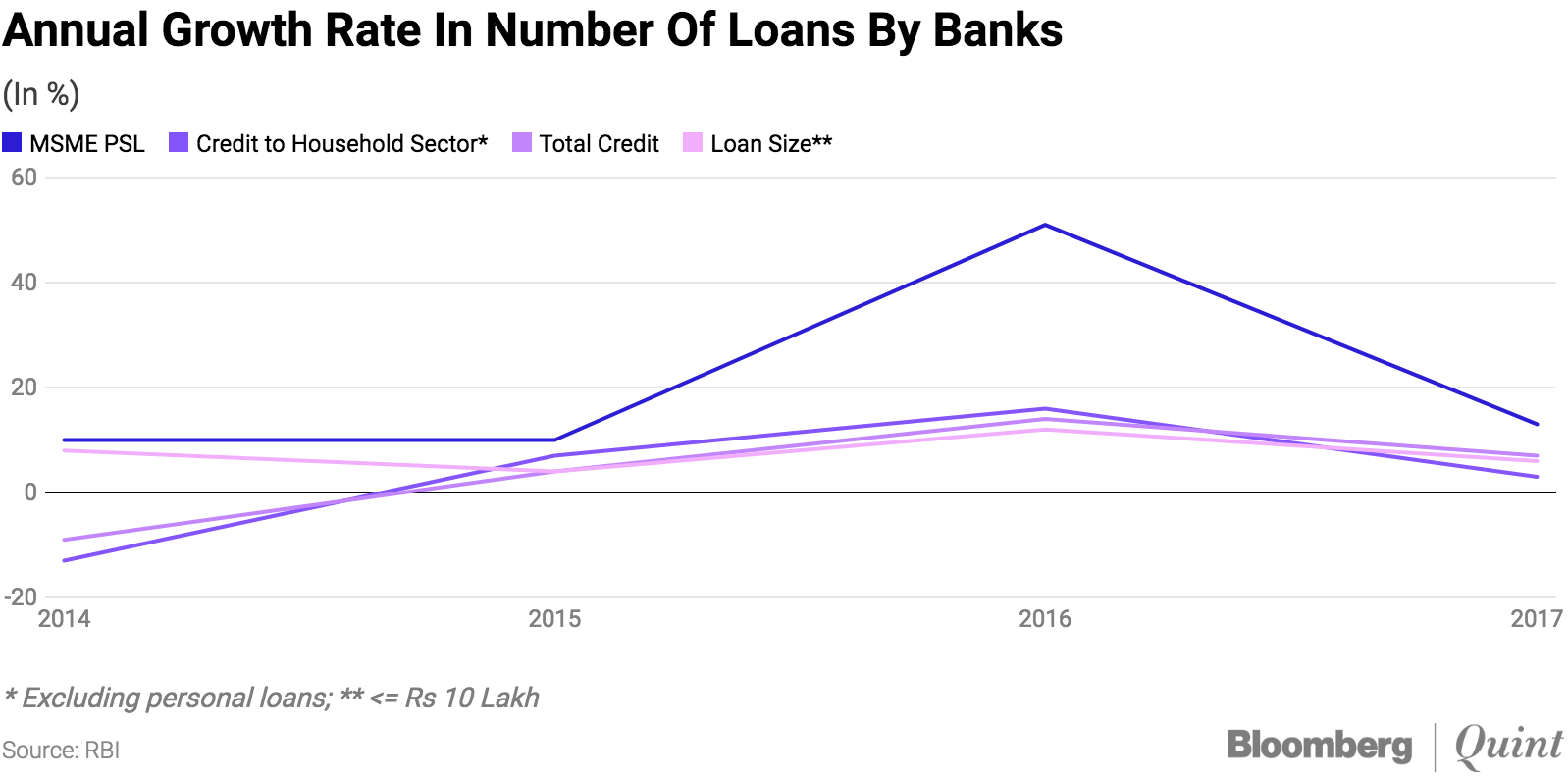

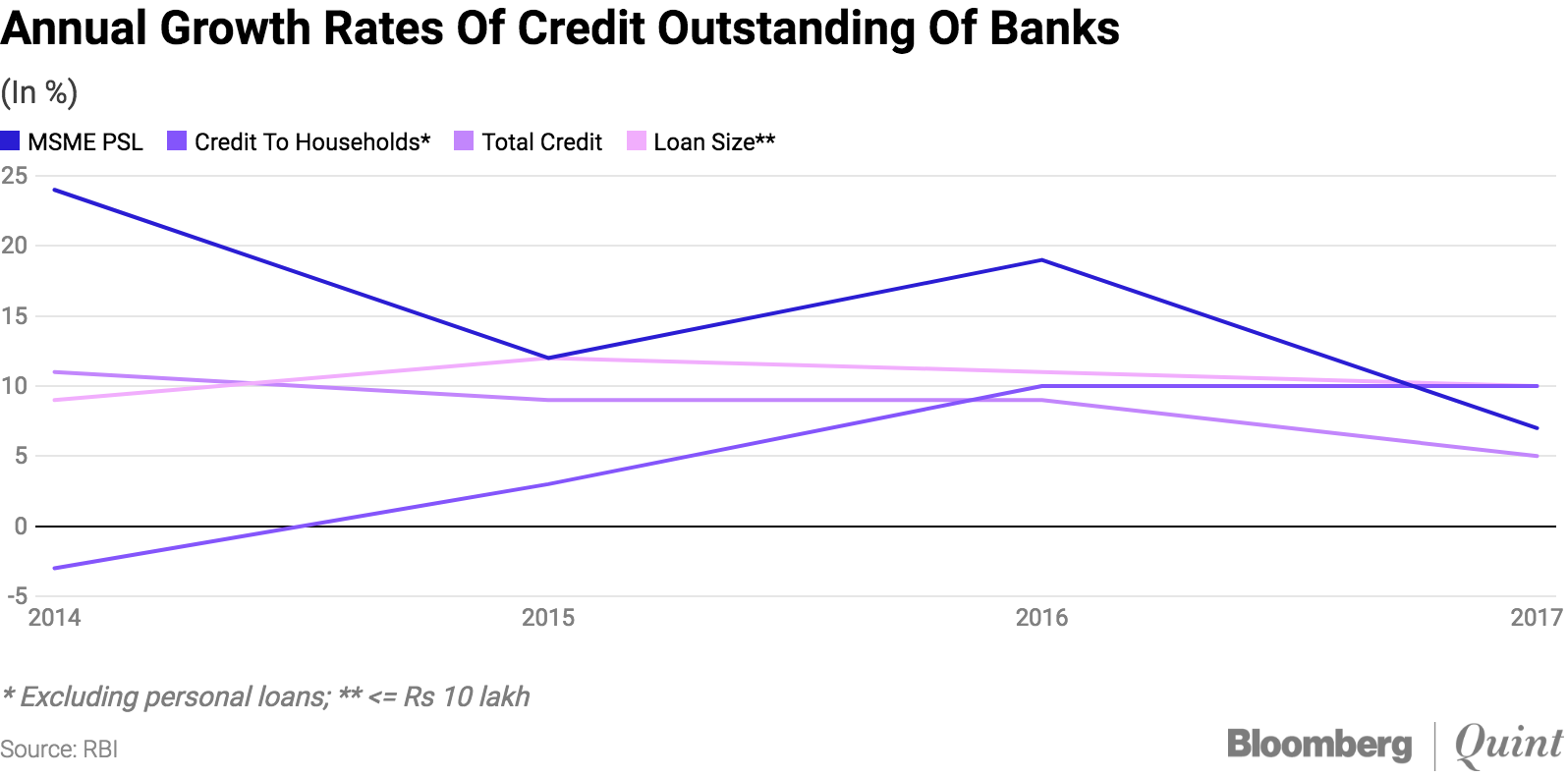

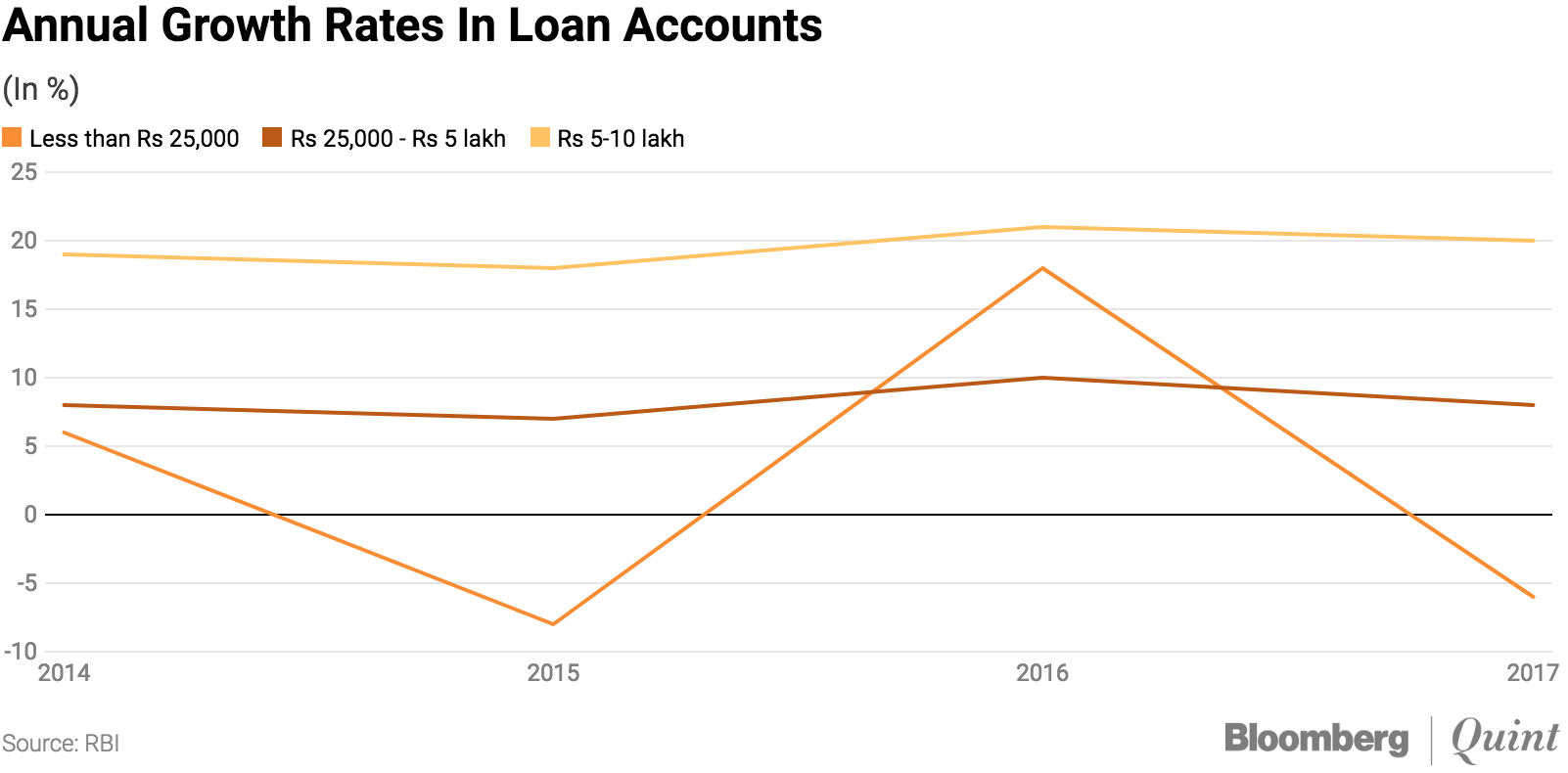

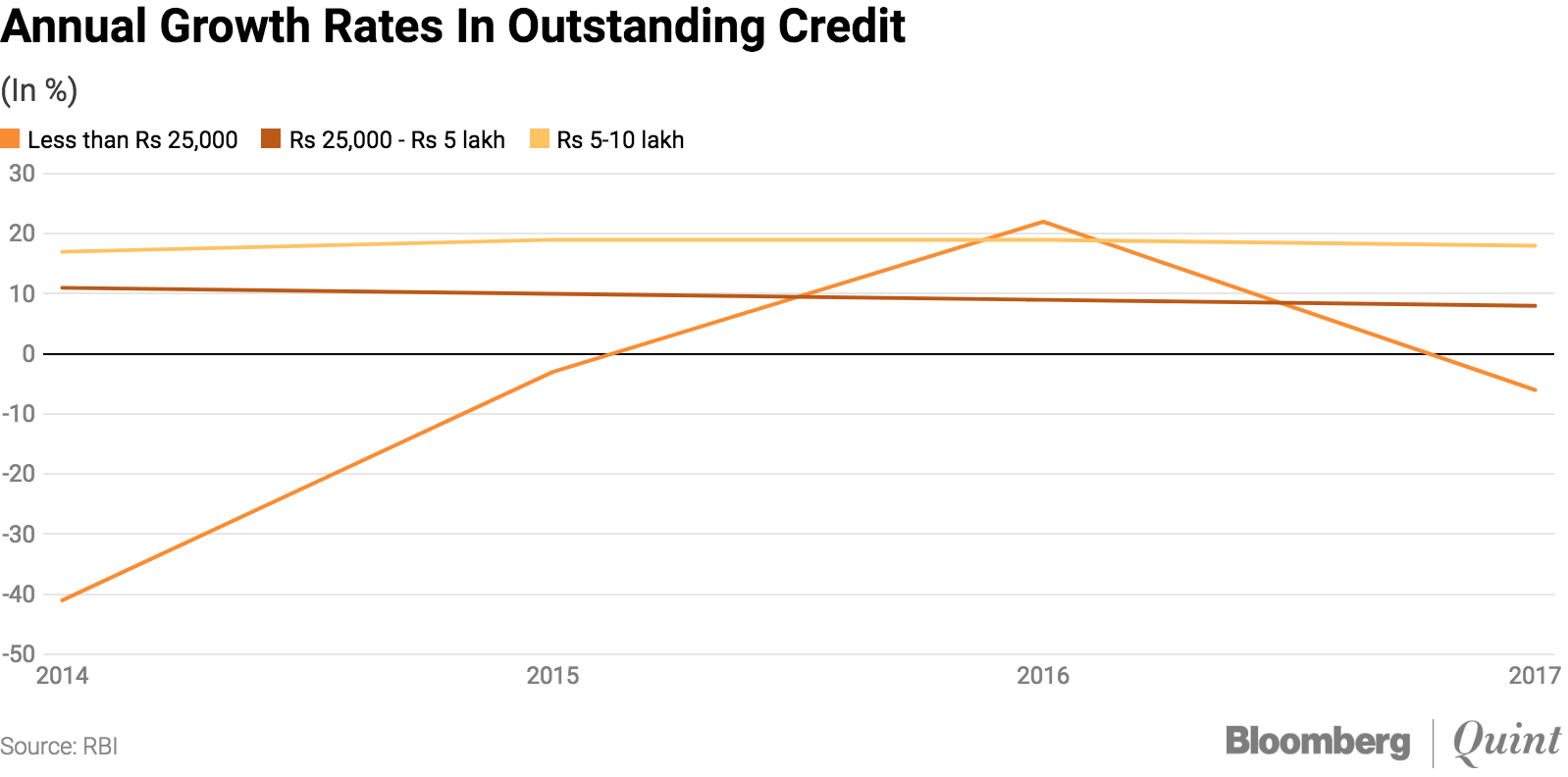

Mudra was introduced in April 2015, and during the relevant period of FY14-FY17, the banking system saw a decline in the overall annual growth in outstanding credit from 11 percent to 5 percent. Concurrently, priority sector lending credit to MSMEs showed a spike in FY16 due to ‘medium enterprise’ loans being given PSL status from April 2015. We carried out an analysis of loan-sizes below Rs 10 lakh for cash credit, overdrafts, demand loans, packing credit and medium and long-term loans.

We found that only for loans less than Rs 25,000 was there a steady growth in FY2016. Since it is possible that many of these loans would qualify as Shishu loans under Mudra, this effect could well be due to Mudra and can be possible evidence for its impact in this category. However, this momentum was not sustained as seen by a decline in the opening of new accounts in FY17. Therefore, an increase in Mudra targets for banks may not have translated into sustained increases in lending to this sub-category of enterprises. We observe a similar increase in both number and quantum of credit to the household sector (this excludes personal loans) during FY15 and FY16 and a subsequent decrease in 2017, indicating that there might be some positive effect of Mudra that has not been sustained. We can conclude that so far, Mudra does not seem to have significantly altered secular trends in lending to the target segments.

For FY17, the banking sector (excluding small finance banks) had a Mudra sub-target of Rs 1.14 lakh crore that banks were able to achieve. The target amounts to 69 percent of fresh disbursements in loans up to Rs.10 lakh, and 67 percent of loans to the household sector for the year. We assume that a simple difference of year-end outstanding is net of repayments and is hence a good indicator of fresh disbursements. Therefore, the targets that were set do not require any ramping up of existing lending operations of banks and they cannot be expected to drive any substantial increase in lending.

The year-over-year growth in Mudra loans is heavily linked to the expansion of the scheme since 2015, and the inclusion of an increasing number of lenders – actual increases in new disbursements will become clear once all onboarding efforts are completed.

At an average loan size of Rs 23,317 for a Shishu loan in FY17, the SFB/MFI channel sanctioned 60 percent of all Mudra loans. Driven by this channel, loans to women formed 98 percent of Shishu loans and 73 percent of all Mudra loans in FY17.

The real benefit from Mudra, where government funds get deployed for financing activities, is the Rs 3,256 crore refinance that it has provided till March 2017. This represents less than 2 percent of the Rs 1,80,000 crore Mudra loans sanctioned. A rupee of refinancing can enable an additional rupee of new lending to the enterprise sector, assuming that the only bottleneck is a paucity of lendable funds in the system.

Since pricing is not risk-based, it provides no incentive to well-performing entities to lend more. It also does not reach lower-rated entities struggling to get funds for their operations, many of which would be small. Refinance in the current form is therefore unlikely to have a non-linear impact on the funding needs of the sector.

The credit guarantee, also a part of the scheme, is provided from the Credit Guarantee Fund for Micro Units and is managed by the National Credit Guarantee Trustee Company. This facility is inadequate to bring down borrowing costs if it does not translate into rating upgrades for lenders. Of the 46 registered lenders, 13 availed this facility in 2016-17, covering Rs 6,910 crore in loans, according to the Mudra Annual Report.

Since MFIs are ineligible due to an interest rate cap of 12 percent applied by CGFMU for Shishu loans, a bulk of the guaranteed loans were to men and at least half of all exposures were in South India (according to the NCGTC Annual Report), implying a significant regional skew.

Benefits that Mudra provides in its current form are not poised for creating a catalytic impact on meeting credit demand. A redesign of the scheme is the need of the hour if Mudra’s funds are to be leveraged to bring about a true multiplier effect.

This article first appeared on Bloomberg Quint