In the first part of this series, we introduced the objectives and motivations for undertaking this study. Our study seeks to create intuitive and comprehensible consent artefacts under the Account Aggregator (AA) framework that are suitable for non-tech-savvy customers. It is well-established that customers rarely read and can rarely comprehend consent artefacts (Bailey, et al., 2018). Further, even if customers read the consent artefact, they are challenged by information asymmetries and bounded rationality that limit their understanding of what they are consenting to (Gomer, n.d.) These obstacles lead customers towards passively engaging with consent artefacts and making sub-optimal or half-informed consent decisions (Sinha & Mason, 2016).

Yet, this decision-making process is nuanced in its own right as we recently discovered in our conversations with sixty low-income, mostly new-to-tech, and some non-smartphone using respondents.

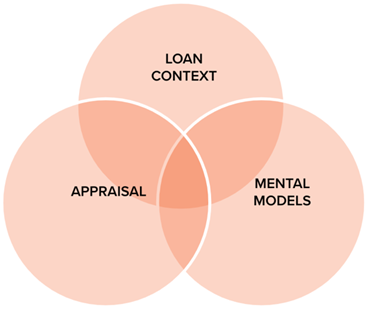

From our conversations and behavioural literature, we gather that the customer’s decision-making process is driven by an interplay of (i) the context or environment in which the decision must be made, and (ii) the conscious and non-conscious mechanisms of decision-making (Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, 2006). Understanding all the factors in this interplay is important to fully understand a customer’s decision-making process, which is often not a linear process based on objective comprehension and analysis of available information. It is a non-linear process where decisions are made at the intersection of three factors – contextual influences, appraisal, and dominant mental models (Kahneman & Tversky, 1984; Johnson-Laird, 1983; So, et al., 2015). Exploring these three axes can help us understand customers’ mental models, framework and identify the barriers to them actively engaging with consent artefacts. This knowledge then equips us with the ability to design consent artefacts that are relevant to them.

We discuss these factors below, taking the use case of a personal loan facilitated by an AA.

1. The context in which customers make consent decisions

Customers seeking loans from a formal lender (banks, NBFCs etc.) must share different kinds of information with the lender while applying for the loan. This includes demographic information, identity proofs, financial information, and now increasingly non-financial information such as access to SMS. Lenders process this information to assess the customer’s creditworthiness and willingness to repay—the two main facets of a lending decision. The AA framework digitises this information-sharing process so that customers can avoid collating and sharing physical documents.

The AA is a class of NBFCs recognised by the RBI which acts as an intermediary for sharing customers’ information after obtaining customers’ consent (Reserve Bank of India, 2016). The AA’s interface integrates with a digital loan application process. Sometimes the customers may be taken away from the environment of the digital lending app and into an AA environment to give consent. In other instances, the AA journey could be integrated into the lender’s app. When customers apply for loans physically, they are redirected to the AA consent artefact via e-mail or SMS. On reaching the artefact, customers must decide about consenting to the AA to share information with the prospective lender (Press Information Bureau, 2021). This is but one part of a larger transaction where customers may engage with many entities other than the lender, including digital lending application providers, originators, sales agents etc. (Press Information Bureau, 2021). This sets the micro and macro contexts in which the customer makes a consent decision.

The consent decision is a micro-decision occurring within a macro-context of applying for a loan (or another financial product) through an AA which sets the meso-context. Customers who engage with the AAs’ consent artefact do so in the wider context of making a loan application. customers start their consent journey motivated by the need to satisfy an urgent short-term or long-term financial need. This motivation sets the context in which customers make the consent decision. Further, through this process, customers face various obstacles that can influence their consent decision-making process. These factors include (i) ability to comprehend technical information, (ii) prior experiences with digital processes, (iii) prior experiences with digital financial processes, (iv) aversion to loss and risk, (v) urgency with which they need a loan, and (vi) their mental model (Taylor, 1999; Nijhawan, et al., 2013; Mazer, et al., 2014).

2. Customers’ appraisal of consent decisions in the AA process

At a broad level, emotional appraisal helps decode the non-conscious decision-making process (their interpretation or evaluation) towards an object/ or stimulus within a particular situation, that determines their subsequent behaviour. It explores how a customer feels about a decision, how they anticipate and evaluate its consequences, and how they perceive the obstacles and enablers preceding it (Arnold, 1960; Roseman, 1984; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985; Frijda, 1986; Scherer & Ekman, 2014). Understanding how a person appraises (or evaluates) situations they are in while making a decision can reflect their underlying motivations, beliefs, and emotions (Scherer, et al., 2001). In the context of AAs, an appraisal would involve a customer’s reaction to being presented with a consent artefact.

The Emotional Appraisal framework is one of the tools that can help unpack how customers appraise a situation into a range of behavioural discriminants or factors (Scherer & Ekman, 2014; Frijda, 1986; Lerner, Han, & Keltner, 2007; Sander, Grandjean, & Scherer, 2005). The stages of emotional appraisal/evaluation of a decision that can be used to understand consent decision-making are:

i. Relevance Evaluation:

At this stage, the customer is exposed to the consent artefact for the first time and the customer processes the information presented to them. The customer evaluates the relevance of the AA process and the consent artefact; for instance, “Is consent relevant for me?”, “Will it help me reach my larger goal of loan approval?”, “Should I pay attention to it?”. This evaluation is affected by a set of factors including –

-

A customer’s familiarity with the process elements; for instance, the AA process and the consent artefact when they encounter it. The more familiar one feels about a process the more relevant it becomes.

-

Alignment with the customer’s internal goals (for instance, obtaining a loan). The relevance of a process is established only when it is aligned with the goal the customer is pursuing.

-

Pleasantness of the experience of encountering the consent artefact or making the consent decision. The degree of pleasantness one feels upon encountering a process can be important to make one see the process as relevant.

- The attention the customer pays to the consent artefact to process the information. Attention is allocated to the processes a customer finds to be relevant.

-

The urgency with which the customer must make the consent decision. Urgency can establish whether a customer feels like a process is worth looking into or if it is relevant at that point in time (Sander, et al., 2005).

ii. Outcome Evaluation:

At this stage, the customer ex ante evaluates the implications and consequences of the decision and its effect on their well-being and their immediate or long-term goals.This evaluation is affected by:

-

Goal conduciveness, or how the customer’s decision assists or restricts their achievement of a set goal. A customer evaluates an action favourably if it is conducive to achieving the necessary outcome.

-

Prior expectations that the customer has about the process affect how they think about the success of the intended outcomes.

-

The causal attribution that a customer perceives between their consent decision and a potential outcome

-

The risk-reward trade-offs surrounding the uncertainty in processing and giving or withholding consent through which the outcome is evaluated.

-

The probability of obtaining a favourable outcome if the customer gives consent (Sander, et al., 2005).

iii. Action Evaluation:

This is the final stage before the customer acts on their decision. At this stage, the customer evaluates their level of control over making a decision and their ability to cope with or face the consequences of doing so. Action evaluation is affected by:

-

The customer’s perceived control over the outcomes of their action.

-

The effort the customer anticipates would be needed to cope with any contingencies (Sander, et al., 2005).

3.Mental Models

Customers’ behaviour and decision-making are influenced by the biases they harbour and the heuristics they come across (Kahneman, et al., 1982). These biases and heuristics create systematic deviations in a customer’s decision-making process. Customers develop mental models building on these biases and heuristics. Customers use these mental models to appraise decision-making. Understanding these mental models, therefore, help explain the customer’s reasoning and inferences underlying their appraisal process (Gentner & Stevens, 2014).

In the context of AAs, a customer’s mental model can affect how they evaluate the risk involved, the relevance of privacy, and the benefits and consequences of making a consent decision. For instance, some customers may believe that tangible documents are less susceptible to leaks or are safer than digital documents (Lammel, et al.; Atasoy, et al., 2022). Or they may feel safer in transacting with familiar people/providers because they are more trustworthy. (Gefen, 2000; Alarcon, et al., 2018) Similarly, they may believe that loan processes are time sensitive and that they must make decisions quickly. Some other mental models may involve customers believing that –

-

The loan application cannot proceed without consent.

-

Bank work has always required signatures and consent

-

Fraud happens online and therefore online/digital processes are less preferable (Msweli & Tendani, 2020).

Click here to access the third part of the series.

References:

Alarcon Gene, M., Lyons, J. B., Christensen, J. C., Bowers, M. A., Klosterman, S. L., & Capiola, A. (2018). The role of propensity to trust and the five factor model across the trust process. Journal of Research in Personality, 69-82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.05.006

Arnold, M. B. (1960). Emotion and Personality: Psychological aspects. Columbia University Press.

Atasoy, Ö., Trudel, R., Trudel, T. J., & Kaufmann, P. J. (2022). Tangibility bias in investment risk judgments. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2022.104150.

Bailey, R., Parsheera, S., Rahman, F., & Sane, R. (2018, December). Disclosures in privacy policies: Does notice and consent work? From NIPFP: https://macrofinance.nipfp.org.in/releases/BPRR2018_Disclosures-in-privacy-policies.html

Dijksterhuis, A., & Nordgren, L. (2006). A Theory of Unconscious Thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 95-109. From https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00007.x

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Gefen, D. (2000). E-commerce: The Role of Familiarity and Trust. Omega, 28(6), 725-737. doi:10.1016/s0305-0483(00)00021-9

Gentner, D., & Stevens, A. L. (2014). Mental Models. Psychology Press. From books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=G8iYAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=aNuLTT

Gomer, R. (n.d.). Designing for meaningful consent. From https://www.ttclabs.net/news/designing-for-meaningful-consent

Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1983). Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference, and Consciousness. Harvard University Press. From https://books.google.co.in/books?id=FS3zSKAfLGMC&lr=&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341-350. From https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341

Kahneman, D., Slovic, S. P., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press.

Lammel, S., Ion, D., Roeper, J., & Malenka, R. C. (n.d.). Projection-Specific Modulation of Dopamine Neuron Synapses by Aversive and Rewarding Stimuli. Neuron, 70(5), pp. 855-862. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.025

Lerner, J., Han, S., & Keltner, D. (2007). Feelings and Consumer Decision Making: Extending the Appraisal-Tendency Framework. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7(3), 181-187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70027-X

Mazer, R., Carta, J., & Kaffenberger, M. (2014, August). Informed Consent: How do we make it work for mobile credit scoring? From CGAP: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/Working-Paper-Informed-Consent-in-Mobile-Credit-Scoring-Aug-2014.pdf

Msweli, N. T., & Tendani, M. (2020). Enablers and Barriers for Mobile Commerce and Banking Services among the Elderly in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Responsible Design, Implementation and Use of Information and Communication Technology, 12067, 319-330. From https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7134387/

Nijhawan, L. P., Janodia, M. D., Muddukrishna, B., Bhat, K., Bairy, K., Udupa, N., & Musmade, P. B. (2013). Informed consent: Issues and challenges. Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology and Research, 4(3), 134-140. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.116779

Press Information Bureau. (2021, September 10). Know all about Account Aggregator Network – a financial data-sharing system. From Press Information Bureau: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1753713

Reserve Bank of India. (2016). Directions regarding Registration and Operations of NBFC-Account Aggregators under section 45-IA of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. From Reserve Bank of India: https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/bs_viewcontent.aspx?Id=3142

Roseman, I. J. (1984). Cognitive determinants of emotion: A structural theory. Review of Personality & Social Psychology, 11–36.

Sander, D., Grandjean, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2005). A systems approach to appraisal mechanisms in emotion. Nerutal Networks, 18(4), 317-352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2005.03.001

Scherer, K. R., & Ekman, P. (2014). Approaches To Emotion. Psychology Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315798806

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (2001). Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research. Oxford University Press. From https://global.oup.com/academic/product/appraisal-processes-in-emotion-9780195130072?cc=us&lang=en&

Sinha, A., & Mason, S. (2016, January 11). A critique of consent in information privacy. From The Centre for Internet & Society: https://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/a-critique-of-consent-in-information-privacy

Smith, C. A., & q Ellsworth, P. C. (1985, April). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 48(4), 813-838.

So, J., Achar, C., Han, D., Agrawal, N., Duhachek, A., & Maheswaran, D. (2015). The psychology of appraisal: Specific emotions and decision-making. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(3). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.04.003

Taylor, H. (1999). Barriers to informed consent. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 15(2), 89-95. doi:10.1016/s0749-2081(99)80066-7

Cite this blog:

APA

Nishan Gantayat, A. A. (2022). The behavioural mechanics that make notice-and-consent models ineffective. Retrieved from Dvara Research.

MLA

Nishan Gantayat, Anushka Ashok, Beni Chugh & Srikara Prasad. “The behavioural mechanics that make notice-and-consent models ineffective.” 2022. Dvara Research.

Chicago

Nishan Gantayat, Anushka Ashok, Beni Chugh & Srikara Prasad. 2022. “The behavioural mechanics that make notice-and-consent models ineffective.” Dvara Research.