Germany was the first country to introduce social health insurance at the national level. Its statutory health insurance system has developed and evolved significantly since its inception as a Bismarckian model (to be explained later), through the course of time to its adoption of principles of competition. Backed by one of the highest total expenditures in health among OECD countries (see Table 1), it has provided health coverage to 100% of its population. While its DALY rate is comparatively high, it has low infant and maternal mortality rates. In this post, we analyse the SHI system and its role in universal health coverage, while acknowledging the role of solidarity in its foundation.

Table 1: Health system indicators in OECD countries

| Country | Total Health Expenditure | Govt. share | Under 5-MR | DALY rate | Maternal Mortality Rate |

| Australia | $ 4,919 | 68.7% | 3.6 | 25598.6 | 6 |

| France | $ 5,274 | 83.7% | 4.5 | 27289.2 | 8 |

| Germany | $ 6,731 | 85.1% | 3.8 | 32162.2 | 7 |

| Israel | $ 2,903 | 64.8% | 3.7 | 19702.2 | 3 |

| Sweden | $ 5,754 | 85.1% | 2.6 | 26888.1 | 4 |

| Switzerland | $ 7,138 | 66.8% | 4.0 | 25581.3 | 5 |

| United Kingdom | $ 5,268 | 81.7% | 4.3 | 29324.8 | 7 |

| United States | $ 10,948 | 82.7% | 6.5 | 33866.3 | 19 |

Note: The values above are the latest available figures for each country (2019/2020)

Statutory Health Insurance System

The Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) system is a mandatory[1], contribution-based system providing health risk cover through an exhaustive benefits package which includes diagnosis, ambulatory (outpatient) care, and inpatient treatment along with prevention and health promotion initiatives at the workplace. Consumers can choose among the 105 not-for-profit sickness funds and are allowed to switch every 18 months.

The system is marked by its self-governed nature with associations at the municipal, state and federal level. Negotiations over prices and services occur among the regional associations of physicians (SHI employed), providers and sickness funds. The sickness funds sign collective contracts with regional associations of ambulatory physicians, dentists and hospitals. Federal associations represent these regional associations at the national level. The fracturing of outpatient care (ambulatory physicians) from inpatient care (hospitals) is the result of a political compromise which came in response to the conflicts between office-based doctors and sickness funds. Initially, it created the system of joint self-governance characterised by regional associations and collective negotiation. Later, the physicians lobbied and successfully obtained a monopoly over out-patient services and essentially split this service from hospitals which then confined themselves to inpatient care. This development remains a drawback in the present, impairing coordination within the health system which is especially important in the case of chronic diseases. The introduction of disease management programs[2] and integrated care programs (explained later) were aimed at filling this gap in the SHI system.

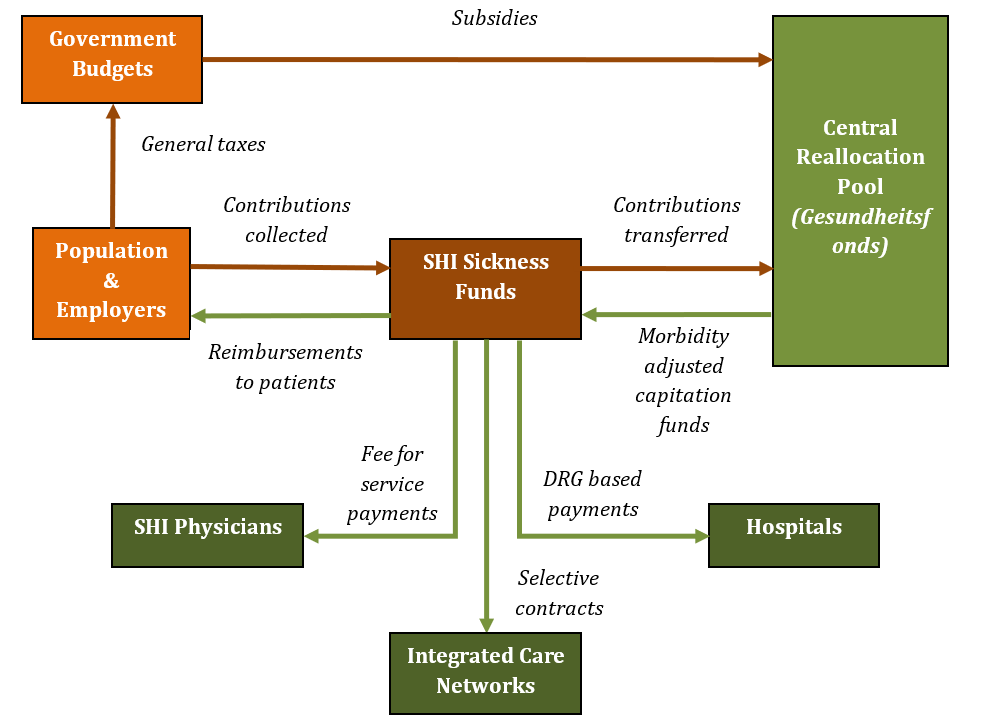

Mandatory wage-related contributions and supplementary contributions from employers and employees are the primary source of funding for the system, supplemented by tax-financed budget subsidies (see Figure 1). The contributions are collected by the sickness funds and transferred to the Central Reallocation Pool (Gesundheitsfonds) to be pooled with the government subsidies. Allocation of funds from the pool to the sickness funds occurs in a morbidity-based risk adjusted scheme[3] (Morbi-RSA). Such adjustment is used to disincentivise risk selection by sickness funds.

Figure 1: Financing Flow in the SHI System

The Morbi-RSA scheme provides capitated payments to sickness funds which in turn pay the physicians on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis and hospitals on a diagnosis-related group (DRG) basis (Figure 1). FFS payments can induce moral hazard in providers (over-provision) since they get paid for each service provided. However, it is also to be noted that the inclusion of preventive care services in the SHI benefit package (in 2000) was followed by an increase in the primary preventive care spending from €1.10 to €4.33 per person covered by SHI between 2000 and 2010. Such increased use of preventive services would augur well for both consumers and sickness funds in terms of reduced curative healthcare costs in the future.

The DRG payment model is outcome focused[4] and incentivises cost control but can also lead to benefits denial and risk selection as healthier patients within a disease category are preferred in order to control costs. Moreover, geographic risk selection can still occur since it is easily determined and not adjusted for in the Morbi-RSA scheme. This “cream skimming” has been observed as sickness funds avoid patients from high-cost regions by avoiding their customer service calls. Therefore, an incentive for risk selection can persist despite the presence of risk adjustment mechanisms. A recently passed (February 2020) regulation has now added a regional component to the list of risk adjusters under SHI.

Since sickness funds are paid on a capitated basis, they usually cannot change their prices to provide value-added services. Consequently, funds were allowed to create tariff structures in 2007 to provide differential charges like higher co-sharing arrangements to attract wealthy, low risk consumers. Cost-sharing arrangements in the form of co-pays and co-insurance are levied to prevent moral hazard. Consumers can also cover these payments by availing supplementary private health insurance (PHI).

While the prices for these payment models are negotiated at the association level (collective contracting), selective contracting was introduced as an option in 2000, which marked the beginning of integrated models within the SHI system.

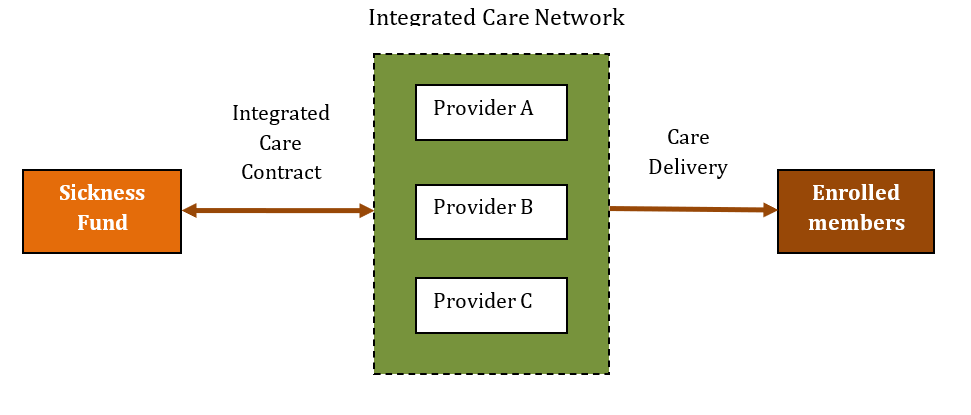

Figure 2: Integrated Care Program

Integrated Care Programs (ICPs) were introduced as one of the reforms aimed at cross-sectoral cooperation and fostering competition to improve quality through managed care. SHI sickness funds can participate in such ICPs to provide coordinated care to their members in addition to the standard benefits provided under SHI. The initial formation of ICPs occurred through a two-step process (Figure 2). Providers came together to form an integrated care network (ICN) which then contracted with a payer i.e. sickness fund through an integrated care contract (ICC). The flexibility to choose the payment method in such contracts has given rise to FFS, capitation and pay for performance (P4P) models. While the providers continue to be paid under the FFS system by SHI, the additional services under the ICP are paid through one of these models[5]. Why such varied payment models were deemed necessary for the add-on services and what incentives they sought to promote, are questions that require further research. The physicians in such networks can also act as gate-keepers to specialists, a feature otherwise absent in the SHI system. The general physicians hence guide the patient in the fragmented healthcare system improving coordination of care. The thrust on preventive and promotive care in such programs is beneficial to members’ wellbeing and helps in cost containment for the funds.

Evolution and Reforms in the System

Contextual factors, mainly political, have shaped the features and functioning of the SHI system since its introduction to its current state. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck established the Social Health Insurance (SHI) system in 1883 along the lines of solidarity with its decentralised structure, contributions according to ability to pay, provision according to need and shared contributions with employers. Such a universal, mandatory health system came to be known as the Bismarckian model of health insurance. It built on previously existing sickness fund structures like industrial workers’ mutual-aid organisations and company-based mutual schemes and gradually increased coverage by including more classes of workers. Eventually mandatory SHI supplemented by PHI and other specific government schemes aided in achieving universal health coverage.

After the inception of the system in 1883, it has undergone multiple reforms over the years to control costs and improve quality through competition. An important reform was the introduction of the option of selective contracting (ICPs) which was later supplemented by start-up funding in 2004. Another measure geared at stimulating competition was the introduction of free choice to consumers in 1993 wherein they could enrol in any of the sickness funds as opposed to their options being restricted to those funds that were affiliated with the association in their region.

Conclusion

Germany’s SHI system provides multiple lessons for health systems design. Its decentralised nature with regional associations facilitates negotiations among representatives of the stakeholders. While collective contracting through such associations remains the overarching feature of the system, it has evolved through government intervention. The role of regulation has been instrumental in introducing integration and supporting its growth through government sponsorship. Furthermore, it seeks to learn from the limitations of collective contracting to make room for innovative payment models to incentivise provision of coordinated and quality healthcare.

References

Amelung, V., Hildebrandt, H., & Wolf, S. (2012). Integrated care in Germany—A stony but necessary road! International Journal of Integrated Care, 12, e16.

Bauhoff, S. (2012). Do Health Plans Risk-Select? An Audit Study on Germany’s Social Health Insurance (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2170664). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2170664

Blumel, M., & Busse, R. (2020). International Health Care System Profiles—Germany. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/germany

Blumel, M., Spranger, A., Achstetter, K., Maresso, A., & Busse, R. (2020). Germany: Health system review 2020. European Health Observatory/World Health Organisation,22(6). https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/germany-health-system-review-2020

Busse, R., Blümel, M., Knieps, F., & Bärnighausen, T. (2017). Statutory health insurance in Germany: A health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. The Lancet, 390(10097), 882–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31280-1

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. (2013). Eurohealth: Incentivising integrated care. Eurohealth, 19(2). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332867

Gottret, P., & Schieber, G. (2006). Health Financing Revisited: A Practitioner’s Guide. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/7094

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2021). GBD Results Tool. Global Health Data Exchange. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Milstein, R., & Blankart, C. R. (2016a). Special Care in Germany. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Better-Ways-to-Pay-for-Health-Care-Background-Note-Germany.pdf

Milstein, R., & Blankart, C. R. (2016b). The Health Care Strengthening Act: The next level of integrated care in Germany. Health Policy, 120(5), 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.04.006

OECD. (n.d.). Health resources—Health spending—OECD Data. OECD. Retrieved August 12, 2021, from http://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm

OECD. (2019). Germany: Country Health Profile 2019. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/publications/germany-country-health-profile-2019-36e21650-en.htm

Paglione, L., Baccolini, V., Marceca, M., & Villari, P. (2018). The Governance of Prevention in Germany. The Governance of Prevention in Germany, 2018-vol. 3. https://doi.org/10.19252/0000000AC

Roberts, M., Hsiao, W., Berman, P., & Reich, M. (2008). Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195371505.001.0001

World Bank. (2021a). Life expectancy at birth, total (years) | Data. The World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN

World Bank. (2021b). Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births) | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT

World Bank. (2021c). Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births) | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT

[1] Employees whose gross income exceeds the opt-out threshold can choose to avail private health insurance instead of SHI. Nevertheless, it is mandatory to be covered by health insurance, whether SHI, private or other schemes.

[2] Disease management programs create structured pathways especially for patients suffering from chronic diseases. Herein the physicians direct the consumers to the required care in the fragmented health system.

[3] This scheme was an improvement over the previous risk adjustment scheme (along the lines of age, gender and invalidity status) since it subsidises the sickness funds for the real morbidity risks arising from these risks as well as pre-existing diseases of its consumers.

[4] The providers are paid a fixed amount for each disease placing the onus on the hospital to reduce unnecessary costs and optimise treatment procedures.

[5] One such ICP, Gesundes Kinzigtal was formed by two sickness funds that signed a contract with a network of providers to offer such integrated care to their members free of cost. It has an innovative payment model where providers are paid P4P for services provided and bonus sums for meeting targets (patient compliance, regular diagnosis) and providers also share profits with the sickness fund from saved costs.

Cite this Item

MLA

(Nambiar, Universal Health Coverage through Statutory Health Insurance in Germany 2021)

APA

(Nambiar, Universal Health Coverage through Statutory Health Insurance in Germany)

Chicago

(Nambiar, Universal Health Coverage through Statutory Health Insurance in Germany)