Did you know that only half the adult population in the world has access to a bank account? More than 3 billion people don’t have access to savings accounts, and they are predominantly the world’s poorest people who live on less than US$2 per day.

Imagine that you were one of them. You don’t have a savings account, an ATM card, or a check book. You are probably thinking: if I lived on less $2 per day, why would I need a bank account? You live hand to mouth. You can’t plan for the future. You can’t save.

I’d like to challenge you to think about savings in a different way. Savings accounts aren’t just for the well off. The fact is everyone needs ways to manage money – especially the world’s poor. Poor households with access to savings not only have a tool to help them manage emergencies and other unexpected events, they also have a tool to help lift themselves out of poverty.

Imagine for a moment that you were one of the 2.5 billion people living on less than a $2 per day. What’s that like? Imagine how hard it is to survive on that. Survive you would, you’d have no choice. But just imagine how much you’d value the extra $1 or $2 you make on a good day, when opportunity came your way. You ought to have a safe place to store that little treasure. You want to be able to store those small daily amounts to be able to draw on them during the bad days. If possible, you’d want them to accumulate over a period so that you can buy something more substantial with that money.

So if you don’t have a bank account, how would you save? Informal methods of saving are risky and expensive and force you to bleed enormous amounts of cash. A study in Uganda, for example, showed that among households without access to bank accounts, 99% of the people surveyed lost an average of 22% of the amount saved in the informal sector.

But imagine if you had a safe, reliable savings account where you could save a dollar or two at a time and withdraw it easily when you needed it. A dollar or two at a time is not much money but it can have a huge impact in your life.

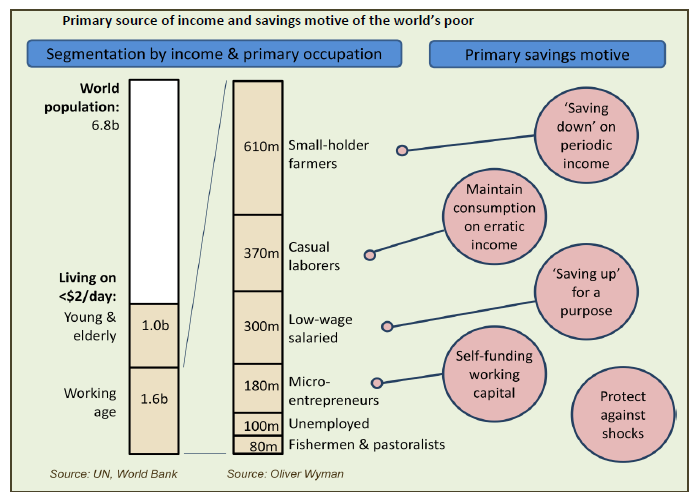

Let me stress how real the need to save by poor people is. Of the 6.8 billion people in the world, almost 40%, or 2.6 billion people, live on less than $2 a day. Let us take a look at who these people are, and in particular the 1.6 billion who are the bread-earners (the other 1 billion are their dependents).

The biggest chunk, 610 million, are small-holder farmers. Do they save? Of course they do, all their income is concentrated in one or two periods during the entire year. Most of the time, they are living off their savings.

Then there are the 370 million casual laborers. Many are paid daily, and they need to insulate their daily expenditures from this income volatility, and that’s a saving story.

The 300 million salaried have more income stability, but still, their daily income is low, they need to accumulate small amounts from their daily wages to be able to pay school fees when they are due or some house repairs. Income comes in small bits, but some expenses are chunkier.

Then there are the 180 million people whose primary occupation is some micro-business. These are the folks that traditional microcredit addresses, but note that it’s a relatively small proportion of the poor. They need money to invest in their micro-business. If you think microcredit is a good opportunity for them, imagine how much more they could do if they could self-fund that through savings and not have to pay interest instead.

And for all of them, savings can protect them against shocks. That’s a big one. We tend to think of the poor as a uniform mass of people who trundle along. The reality is that if you observe a group of poor people over, say, five years, a significant fraction of them will have escaped poverty during this time. The problem is that just as many will have fallen back into poverty because of some kind of shock. A health problem, a failed crop can set them back many years. But if people had good savings cushions or insurance mechanisms, they would be able to weather these shocks without setting them back many years.

We have seen that poor people have a tremendous need for financial services. So the question is: where are the banks in all of this? Why are they not helping more poor people to achieve these small feats with their money?

[Ignacio Mas has written a paper titled “New opportunities to tackle the challenge of financial inclusion” where he reviews the relevance of formal financial services to the poor people and offers interesting solutions to the above questions. Click here to read the paper.]

8 Responses

That low-income households are willing to penalise themselves heavily for 'defaulting' on saving (accept to forego the accumulated saving on missing one saving instalment) proves that they view saving as an important feedback mechanism into their future well-being.

The author's paper presents the business correspondent model of financial inclusion and relaxing regulations for deposit-accepting non-lending institutions as solutions for helping the poor save safely. There are risks associated with both suggestions and one wants to be most careful with the savings of those who have worked very hard indeed to accumulate them but testing them to devise better suggestions will be much better than being too cautious and not doing anything..

It has become clear and generally proved that poor people, want, need and do indeed save. However many studies, including the author’s paper have shown that the poor people are facing an extremely risky environment when they save in the informal sector. A recent study by Microsave in Uganda revealed that 99% of the clients saving in the informal sector report that they have lost some of their savings.

This shows the significant impact that access to savings in formal and semi formal institutions can have on the lives of the poor. However the opportunity cost involved in transacting with the formal institutions and the distance to be covered, puts off a significant chunk of the people from accessing it. As correctly pointed out by the author, the Business Correspondent model and the recent developments in technology can take up in a big way to create access to savings facilities. However, we still have a long way to go to ensure that these Business Correspondent model is viable for all the stakeholders and does not become another run of the mill approach.

I have a question more than a comment. I have a house help who has been with me more than 15 years. I have provided her with interest free loans, which she has repaid promptly and on schedule. My argument with her has always been that if you save before hand then you are not dependent upon me for a loan. But it seems that the need ton save is more when there is a loan staring her in the face.

As an illiterate, she also is intimidated by banks. I plan to open "an account" with me as the banker. So I keep a passbook and allow her to save as much as she wants. Do you think this will work?

hello lfowergirl … i donot know which region u belong to. So cannot comment on the regulatory requirements of that region.

But , i m from india … nd if u too belong to this region, then u must b knowing that we have a KYC requirement which is a must for availling any banking service.

So if ur househelp has ne doc. identifying her as who she is, she can open an account in her own name as well.

And if she does nt have any such proof, there are NGOs which are employed by PSU banks to facilitate such unpriviledged citizens in availing bankings services.

for more info u cn contact me on my id – maharshi_mehta2089@yahoo.com [ nd plz do mention some reference]

flowergirl … i m keen to know hw it fared following bindu's words.

I STRICTLY WISH … if u hv not acted upon her words then do not do so.

– Maharshi

@ Flowergirl: thanks for your post. We see this phenomenon all the time as well. Loans acts as "forced savings". It seems like the commitment to repay is a feature that individuals value. Voluntary savings don't quite have the same effect.

Idea for you: continue to give her a loan. Now charge an interest rate on the loan (say 20%) – sweep the interest payments into a separate account that then becomes her savings corpus at the end of the period when the loan is repaid. This way, you have helped her accumulate a surplus so that she can borrow that much less next time around.

Let us know how it goes!

How do you define "poor"? may be this qualifes as the dumbest question of the century but if we are talking about people who are struggling to make ends meet, then where is the opportunity for them to save? and to this illiteracy, not to mention the complexities of the processes of banks and available financial instruments…

Lending to a person you know for 15 years vs lending to a person you know for 15 days vs lending to a person you know for 15 minutes are all different cases. The house help who is loyal today because her master trusts in her and lends her interest free loans might not hold the same feeling if she comes to know that the same master is going to hence forth charge her (20%) interest in future. she is in need and hence has to borrow. she has to undergo what ever hardship it takes to return the loan back to maintain the trust. and what does the master do in return? burden her further with an interest…. and if there is a corpus, why would she borrow her own corpus money next time only to pay interest on top of it? I am eager to know how the help behaves!