Background

As of May 2021, most of the social protection measures introduced by governments in response to COVID-19 are in the form of social assistance, i.e., non-contributory cash or in-kind transfers targeted at low-income or vulnerable households. Of these, cash transfers (conditional and unconditional) remain the predominantly used instrument by both national and sub-national governments.[2] In India as well, both the Central and state governments provide social assistance through a slew of cash transfers, delivered through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) system.[3] The DBT apparatus, introduced in 2013, relies heavily on the existing banking infrastructure to transfer funds to beneficiaries, with various programmes using Aadhaar for verification.[4] Consequently, effective service delivery under such a system rests upon a variety of factors — end-to-end digitization of records, error-free seeding of Aadhaar with beneficiaries’ bank accounts, efficient back-end payment and information systems, and a fully working cash-out architecture. However, inadequacies in the aforesaid components persist, leading to suboptimal outcomes for beneficiaries in the last mile. A detailed typology of such last-mile delivery challenges, in the form of an exclusion framework, has been provided in one of our previous posts.

Overview of the Research Study

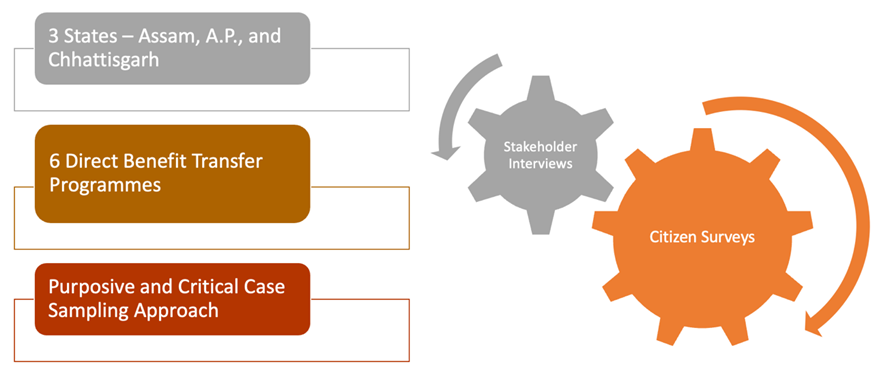

It is against this backdrop that we, in collaboration with Haqdarshak, undertook a three-state study to document the challenges faced by citizens in accessing cash transfers under DBT. Under this research collaboration, we surveyed over 1500 citizens across a total of six districts in Assam, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh (A.P.). We covered six DBT programmes, namely, Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana (PM KISAN), Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP), Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana (PMAY), Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), and Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY). A total of 80 citizens were sampled under each scheme in each of the three states, except for PM Kisan in Assam and PMAY (in all three states).[5]

While the states and districts in the study were selected through convenience sampling, the citizens were selected through purposive sampling, i.e., we only selected those citizens who had faced or were facing challenges in accessing benefits under a given DBT scheme. Wherever possible, we also ensured that the sample selected for a given scheme in a particular district, was representative of a range of issues (enrolment-related issues, payment failures, etc.). For any retrospective information that required the respondents to recall details, we limited ourselves to a period of one year, to ensure the reliability of data collected. In addition to the citizen surveys, we interviewed a range of stakeholders responsible for the delivery of these cash transfers. These included government functionaries such as panchayat officials, block and district-level bureaucrats, and private actors such as the Village Level Entrepreneurs (VLEs), bank managers, banking agents, etc.

Figure: Overview of the Dvara-Haqdarshak Study on Exclusion in Government to Person Payments

The broad research questions the study attempted to explore have been provided below:

- What are the various kinds of challenges citizens face in accessing cash transfers, across the various stages of scheme delivery (enrolment, back-end processing, and cash-out)?

- How do these challenges vary from one access point to another, for a given scheme? (For instance, are delays in enrolment under PM KISAN more common for citizens applying through a panchayat office vis-à-vis those applying through a Common Service Centre?)

- Similarly, how do these challenges vary from scheme to scheme, district to district, and state to state?

- How do such excluded citizens attempt to resolve their grievances — what are the various channels employed to raise and track complaints?

- What is the average time spent and average cost borne by citizens during such a redressal process?

- What are the various perspectives provided by state actors such as panchayat officials, local government functionaries, block and district-level bureaucratic officials, and non-state actors such as private service providers, in light of the challenges documented for a given scheme in a particular district?

While many rapid assessment citizen surveys, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak, have attempted to document last-mile delivery challenges in government schemes, this study seeks to curate those issues using an all-encompassing framework that spans the various stages of scheme delivery. The study provides a diverse taxonomy of exclusionary factors in DBT delivery, against a backdrop of localized contexts, that vary from state to state. It also brings forth supply-side perspectives with respect to last-mile delivery, through detailed interviews of stakeholders across three tiers (village, block, and district).

In the next set of blog posts in this series, we will provide detailed case studies of citizens facing challenges in accessing DBT payments, across the three states covered.

[1] The author would like to thank the project team and field staff at Haqdarshak for facilitating the citizen surveys and stakeholder interviews under this engagement.

[2] Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Blomquist, J., Dale, P., & Fontenez, M. (2021). Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures. Retrieved 6 December 2021, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33635/Social-Protection-and-Jobs-Responses-to-COVID-19-A-Real-Time-Review-of-Country-Measures-May-14-2021.pdf?sequence=25&isAllowed=y

[3] Under the DBT system, implementing governments transfer the benefit or subsidy amounts directly into the citizens’ bank accounts.

[4] Sengupta, D. (2021). Direct Benefit Transfer – A blessing during the time of Pandemic | National Informatics Centre. Retrieved 6 December 2021, from https://www.nic.in/blogs/direct-benefit-transfer-a-blessing-during-the-time-of-pandemic/

[5] For these schemes, the field team faced multiple issues in identifying citizens that fit the sampling criteria in a given village/block, thereby the total count for these remains less than 80 in some locations.

Cite this Item:

APA

Gupta, Aarushi. 2021. “Direct Benefit Transfers in Assam, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh: Introducing the Dvara-Haqdarshak Study on Exclusion in Government to Person Payments.” Dvara Research.

MLA

Gupta, Aarushi. “Direct Benefit Transfers in Assam, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh: Introducing the Dvara-Haqdarshak Study on Exclusion in Government to Person Payments.” 2021. Dvara Research.

Chicago

Gupta, Aarushi. 2021. “Direct Benefit Transfers in Assam, Chhattisgarh, and Andhra Pradesh: Introducing the Dvara-Haqdarshak Study on Exclusion in Government to Person Payments.” Dvara Research.

One Response

Great post, Aarushi. It will also be interesting to document the challenges faced in accessing these transfers and experiences with grievance redressal mechanism for men and women separately.