As we saw in the previous post, seasonal migrant workers and their families face several endemic disadvantages, both at source and destination. Emerging civil society interventions that seek to reduce these vulnerabilities recognize that financial services offered in tandem with a host of livelihood interventions have the potential to offer social protection and also enhance returns from migration. The protective, preventive, promotive and transformative forms of social protection1 are a useful lens through which one can view the role of financial services and livelihood interventions for migrant communities.

Unni and Rani (2002) assert that the concept of social protection should include promotive measures to improve real incomes and endowments, preventive measures to reduce vulnerabilities and deprivations and protective measures to provide relief from deprivation. In addition to this, Sabates-Wheeler and Waite (2003) provide a conceptual framework on social protection of migrant workers, which also highlights transformative measures that aim to alter the bargaining power of certain groups in the society and focus on empowerment.

The promotive element of targeted financial services has been widely discussed, however, in the context of seasonal migration, the preventive, protective and transformative role of financial services. i.e. its ability to reduce vulnerability, manage risk, create wealth and alter the bargaining power of vulnerable migrant populations has been overlooked.

In recent years, several civil society organizations have begun recognizing the need to engage with migrant communities. Notable among them is the work of Aajeevika Bureau and Shram Sarathi – two specialised organisations set up to provide solutions and security to seasonal migrant workers.

Aajeevika Bureau was established in 2005 as a specialised organisation offering livelihood support services to migrant workers. It started with the premise that the primary resource in agriculturally distressed regions like southern Rajasthan is labour; hence development interventions that focus on enhancing human capital, labour and employment are key to the economic well-being of communities in such regions characterized by high levels of out-migration. Based on this premise, Aajeevika Bureau offers services such as identity and registration, skills training, legal aid and collectivization, enabling access to entitlements for families left behind and health care services for migrant workers through a network of field offices at both source and destination. But it was soon recognized that while livelihood support services were having a direct impact on reducing the vulnerabilities of migrant workers, the existing gaps in financial services to this group also needed to be addressed to enhance the returns from migration.

In view of this, Aajeevika Bureau incubated a non-profit company called Rajasthan Shram Sarathi Association (Shram Sarathi). Shram Sarathi identified that seasonal migrant workers have unique socio-economic needs and hence pioneered a model to provide targeted financial services for migrant workers in India. Shram Sarathi’s model includes a mix of micro-loans at source, informal savings instruments, opening of savings bank accounts, social security linkages, financial literacy and counselling, specifically targeted at migrant workers. Such a targeted model calls for innovations in the design as well as delivery of basic financial services. It also focuses on three key elements of economic choices and vulnerabilities of migrant workers viz. financial planning and management of cash flows; asset allocation and wealth creation; and protection from and diversification of risks.

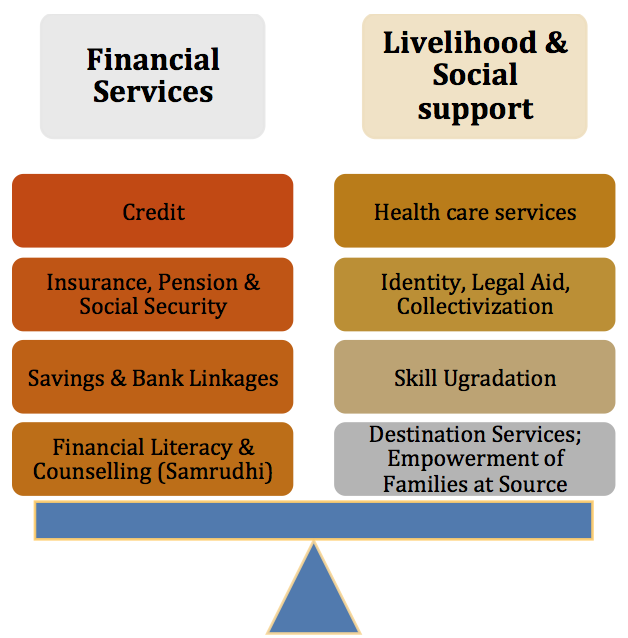

The Aajeevika Bureau-Shram Sarathi model recognizes that social support services and financial services have to be integrated to address the specific needs of vulnerable migrant workers and enable economic well-being of their households. Under this hybrid model, migrant households receive a customized combination of both livelihood support and financial inclusion services. Both sets of services and outreach to migrant households are carried out at both source and destination locations. Such a hybrid model recognizes that financial services cannot operate in a vacuum, without any supportive services that make migration less vulnerable.

Take the example of Javeriram Gameti, an unskilled mine worker from Kumbalgarh. He revealed that incurring debt was in fact a way for him to manage other shocks such as non-payment or delayed payment of wages as well as the incidence of sudden health episodes at the workplace. Several migrants like Javeriram who are absent from their villages for several months are reeling under crippling debt burdens. In the absence of the men, the women left behind find it all the more challenging to raise informal credit at favourable terms. In this context, another migrant who availed a loan from Shram Sarathi to repay an older more expensive debt, said, “There was a time last year, when I was thinking of making my 11 year old son leave school – but he was able to continue due to some credit assistance. I want to go back to work now and ensure that such a situation never comes.”

In this particular case, the availability of timely credit ensured that the migrant could reduce the cost of his future liabilities and spread his repayments over a period of time, instead of one lumpsum settlement. For a migrant family to end up in such a situation of crippling informal debt, which necessitates that the next generation migrate is not uncommon. A simple financial instrument like credit delivered through appropriate channels has the power to act as a preventive tool of social protection, the effect of which is also long term. Yet another migrant who also repaid an expensive informal debt using institutional funds stated that this helped free up his future finances, thereby allowing him to invest more in education and nutrition for his family.

Enabling repayments of older liabilities isn’t the only instance where a simple tool such as credit has demonstrated significant spill over effects on education for example. Babli bai, the wife of a migrant often told us, “Earlier the children could never concentrate and study because 12 members used to live in a two room house”. Two loan cycles later with a house twice as large as earlier, Babli bai now believes that more than the actual security of a home itself, the ability to educate her children comfortably will have far greater future impact. Finance does therefore have a powerful promotive role to play in improving endowments and future incomes.

Nirbhaylal Gameti, who migrates to Bangalore, tells us that he had no form of identity and hence no bank account. Every three months his contractor would settle his dues, however in the absence of a bank account, he was compelled to maintain his savings with the local shop owner in Bangalore. Every time he wished to send money back to his village he would collect his savings from the shop owner, often with unfair deductions.

When Nirbhaylal came in contact with Aajeevika, he was able to obtain a migrant worker identity card authenticated by the state labour department. With the help of this card, he was able to open a bank account and also avoid police harassment during his journeys from Udaipur to Bangalore and back. Nirbhaylal now tells us that because he had a bank account, he was no longer dependent on the shopkeeper and was in fact encouraged to save regularly. His remittances rose from an average of 2000 rupees each quarter to nearly 8000 rupees per quarter. A few years later, while he was in Bangalore, his brother, a migrant as well, was murdered in Surat. Shram Sarathi swiftly offered emergency financing and helped Nirbhaylal bring back his brother’s body back to their village for the last rites. Subsequently, with additional cycle of credit, Nirbhaylal was able to set up a small motor mechanic shop in his village. He hired a young man to run the shop while he migrated to Bangalore. With the additional earnings from the shop he was able to now support both his family and that of his deceased brother’s. For Nirbhaylal, access to finance has multiple meanings. It offered him protection of his money when he most needed it, prevented financial distress when there were sudden shocks and helped promote a local enterprise to diversify incomes and build wealth.

For Gopilal Gameti however, access to finance coupled with a livelihood intervention was also transformative. As a young school dropout, Gopilal spent years moving between multiple unskilled jobs before he was inducted into a skill-building program organized by Aajeevika. As a newly skilled plumber, Gopilal slowly picked up the tricks of the trade and evolved into a skilled worker. An initial loan of 3000 rupees helped him buy basic tools and equipment to start a small plumbing business as a petty contractor. Gradually with additional financing, Gopilal carefully built his contracting business and is now a large contractor, working on multiple projects in Udaipur and Nathdwara.

Gopilal received the opportunity to upgrade his skills that was a pre-condition for helping him avoid stagnation in the labour market. The timely infusion of funds proved to be a critical factor that helped him redefine his position in the labour market and improve his own financial situation. His is a case where the true potential of a livelihood intervention was realized by a significant infusion of loan funds. Younger entrants into the labour markets need to be equipped with technical skills that help them negotiate a better wage and gradually see a rise in incomes. However more significantly, micro-loans provided at affordable interest rates can enable these young trainees to purchase tools and materials and over the years turn into skilled contractors and entrepreneurs.

For Gopilal access to both livelihood interventions and finance was a transformative experience. As a tribal school dropout, the dignity associated with becoming a large contractor (a trade dominated by upper castes) renewed his confidence. The clear shift in his household’s economic situation has also made him a role model in his community. People actively seek his advice and support in financial decisions and he has emerged as a respected thought leader in his community.

Bhanwari Bai has a similar story to share – constantly evolving her identity from being a single mother of two boys to an independent entrepreneur to a community leader. Bhanwari bai’s husband deserted her very early in their marriage and she was left with the task of raising two young boys by herself. Her older son was compelled to migrate to Surat, however Bhanwari bai was determined to educate her younger son. With some credit assistance and technical inputs, she was able to set up a small kiraana store in her village selling small household items. She also joined a solidarity group for women affected by migration and gradually emerged as a peer leader in her community. She says rather emphatically “Earlier I was confined to my home, but because of my shop, I know everyone and more importantly everyone knows me! I didn’t even know who the Sarpanch was, but as a leader of the solidarity group, I know where the Collector sits and who the Tehsildar is. I meet so many people on a daily basis”. Financial confidence and recognition in one’s community can significantly alter one’s viewpoint on migration and in Bhanwari Bai’s case, such transformation is evident.

Financial inclusion of migrant workers therefore cannot be viewed in isolation from their unique social protection needs. In fact it can be viewed as a key component of promotive, preventive, protective and transformative social protection of migrant workers. Conversely the role of financial inclusion for migrant workers is also not limited to offering social protection alone or merely opening bank accounts. Financial inclusion services should enable sound planning that leads to the creation of wealth and makes migration accumulative. It is therefore of significance to expand the scope of financial inclusion of internal migrants to include information flows and services that enable social protection and improve returns from migration for those who are compelled to move in search of work.

—

1 – Unni, Jeemol, and Uma Rani. 2002. Social Protection for Informal Workers: Insecurities, Instruments and Institutional Mechanisms. Geneva: ILO; Sabates-Wheeler, Rachel and Myrtha Waite. 2003. Migration and Social Protection: A Concept Paper. Development Research Centre on Migration Globalisation and Poverty: Working Paper T2. Brighton: University of Sussex.

2 Responses

I was in South Odisha, talking to tribals, some of whom are also migrants. I understand that the problem there is not just the ability to save and have access to financial services, but also understanding the importance of saving. Is that not a problem with migrants from Rajasthan? Are these solely migrants who are migrating in order to obtain funds that they absolutely have to have to keep body and soul together? Re Odisha, I also heard the concept of fashion migrants, who want to migrate to get access to consumption goods, particularly the younger migrants. Does that exist in Rajasthan?

Dear Meylekh, thanks for sharing your comment. Interestingly, most communities do seem to understand the importance of saving. What seems more out of reach is the confidence to sustain savings over a period of time and the availability of suitable and reliable financial instruments to do so. As you pointed out, an ‘aspirational’ movement from villages is common among certain social groups which are relatively better off and well-resourced. Among tribal youth in region, it is a common trend for young boys to drop out of school and migrate – a decision often reinforced by the perceived success of migrants returning from cities with new clothes and mobile phones. However, the overwhelming trend is that of ‘distress’ driven migration which stems from conditions of endemic poverty and social vulnerability in the villages. Much of the income earned from migration therefore is channeled towards consumption expenditures and repayment of informal debts. The challenge here therefore is creating conditions that enable savings for cushioning shocks and accumulation of wealth to fulfill goals that improve their quality of life. This however can only be done by paying attention to the broader context of informal labour and migration that these workers are a part of. Their financial vulnerability or even ability to save, in several ways is intricately linked to their migration choices.