As the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic raged in the country, we witnessed micro-entrepreneurs once again succumb to the economic implications of lockdowns, and this time, it is as they are still picking up the pieces from the disaster that was the first lockdown (WIEGO, 2020). With their source of income cut off, and the lack of any substantial savings, the street vendors of India are faced with the paramount issue of paying back their debt, with many having to avail more loans to fulfil their necessities. Often, these loans have high rates of interest and lead to a vicious debt spiral.

Problem Statement

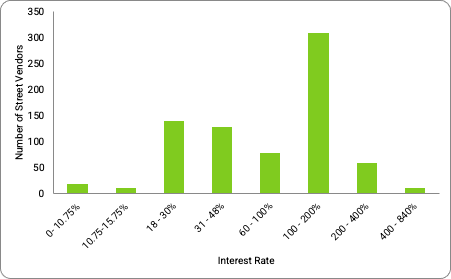

Street vendors are no strangers to debt cycles or high-cost loans (Bhowmik& Saha, 2011). 81% of street vendors borrow money from various sources for their business, and 72% borrow from informal sources, with the average rate of interest being 142.9%. Steps have been taken to address the street vendors’ lack of access to financial benefits, including the setup of Regional Rural Banks, Self Help Groups and various measures from the RBI. Several government schemes have also tried to address the issue, with the latest being the PM SVA NIDHI. This scheme allows street vendors to avail collateral-free working capital loans up to Rs 10,000 of 1-year tenure. These programs, however, have achieved limited success (Vijayabhaskar & Kumar, 2021). They fail to address the persistent need for cyclic loans used as working capital for these businesses, leaving the businessman at the mercy of exploitative informal money lenders.

Figure 1: Interest Rate of Borrowing

In the survey for the BharatBazaar pilot, it was found that vendors borrowed from money lenders on a monthly basis and repaid the loan in weekly instalments. Loan ranged from Rs 10,000 to 20,000. When interviewed. Mr. Ashok, a flower vendor in a Bangalore local market, said that he borrowed Rs 10,000 every 3 months for working capital to keep his business running. The lender deducted Rs 2000 as upfront interest. The vendor then paid back Rs 1000 every week for the next 12 weeks, which indicates he borrowed at the exorbitant interest rate of 160%. Then the cycle restarted. Mr. Ashok said that he has been following this cycle of borrowing ever since he entered the business 7 years ago. Being an outlier, A fruit vendor in that- Mr. Devraj, stated that he did not regularly borrow for his business but took need-based loans of Rs 10,000 following the same structure as the flower vendor, as elaborated above. It is worth noting that while he had an alternate source of income from his son’s salary, Mr. Ashok was the sole earning member of his family. Mr. Devraj also added that while he did not believe in cyclic borrowing and tried to save as much as possible, most of the businessmen of this local market religiously borrowed for working capital. The recurring nature of these loans and their high interest rates lead to vendors being stuck in endless cycles of debt (Ananth, et al., 2007)

The Solution

BharatBazaar aims to create a hyperlocal model that addresses these entrepreneurs’ repeated need for working capital at its root. The solution offered is simple: customers (of the street vendors) themselves fund their working capital needs. BharatBazaar is the tech platform- a mobile application that connects street vendors to their customers and allows customers to place orders and make an advanced payment for their products, thus providing the working capital the vendor needs to procure their raw materials, i.e., goods from the wholesale market. In the app, vendors can catalogue their products and prices, which will then gain them visibility to their customers. The customers can choose a vendor based on the location and need, to place the order and make an advance payment to the vendor. The vendors can offer home delivery in their own capacity or allow the customers to pick up the orders from their shop. Thus, it provides a viable and economical solution for street vendors that comes with a wide array of additional benefits of digitisation.

Figure 2: The Model of BharatBazaar

Workflow Of the Model

Vendors and customers are onboarded to the BharatBazaar platform. Products of the vendor, along with their pricing, are catalogued and available for the customer to access.

The process is started when a customer selects a vendor and places an order. The customer pays their order amount immediately, upfront, using a digital mode of payment to BharatBazaar. The amount is transferred to the vendor digitally, and the order is also communicated in the local language. The cumulative of orders, with their upfront payment, generate daily working capital for the vendor. The cycle is complete with the delivery of the order on the determined day.

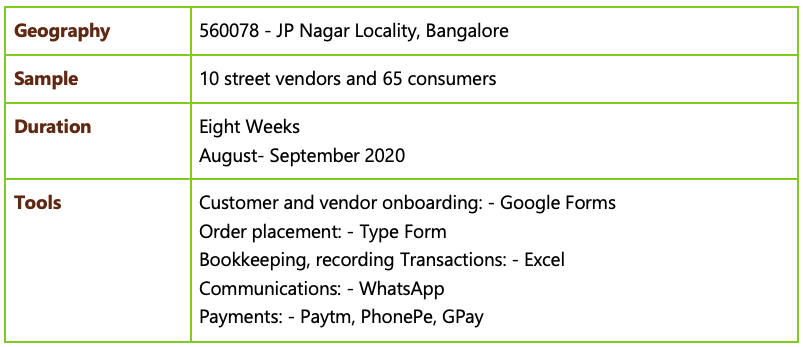

Figure 3: The Pilot – Methodology

Findings

In the initial survey to onboard participants, there was a highly positive response on the part of the consumers. It was found that a large part of the customers had diverted their business to online delivery services for the sake of convenience during the lockdown. The most important incentive for customers to participate in the pilot was supporting local businesses. The sense of altruism was valuable to the customers. Secondly, there was great appreciation for the freshness and the good quality of the produce at competitive prices compared to other large enterprises. The convenience of online ordering and home delivery service was also important to many. Additionally, the participants were comfortable with the use of technology and digital payment methods.

Turning to the other end, there was a high amount of interest expressed by most vendors, where most of them were especially interested in BharatBazaar to mitigate their losses incurred in the lockdown. A common incentive for joining the pilot was additional and assured revenue that could be gained from the orders. The benefits of not having to avail loans by using the BharatBazaar model instead, was much appreciated. There was also some hesitancy among the street vendors and hawkers regarding the technological aspect. They expressed a few constraints that included:

- Lack of literacy

- Lack of access to a personal device

- Lack of knowledge of using digital modes of payment.

Of the vendors who participated in the pilot, 4 of them used devices operated by their children.

On the successful completion of the 8-week pilot duration, it was found

-

Customers are very comfortable ordering online and find the quality and prices of the product competitive. They also derive a sense of satisfaction in knowing that they were helping sustain a local entrepreneur.

-

Once familiarised with the process, the vendors are diligent in delivering good quality products consistently.

-

A personal rapport is built between the consumer and their vendor, leading to more continued engagements.

-

An additional benefit of upfront ordering and payment observed was that when the orders are communicated in advance, vendors could procure rare or unconventional products or products that they did not normally stock for which a customer has placed an order- as they had an assured buyer for that product.

-

Vendors appreciate being able to capture a portion of the market that gave its business to e-commerce players. A valuable benefit of the app to the vendors was the additional revenue they could generate through digitisation.

The BharatBazaar model is feasible and could be a viable and economical source of working capital and can act as a complete replacement to working capital loans with a substantial order volume.

Other interesting points to note include:

-

Vendors are comfortable delivering in their own capacity. It was noted that 2 of them had an agreement amongst themselves and proceeded to make a tie-up with a rickshaw owner in the locality to have their products delivered.

-

Initially, when the idea was pitched jointly to 3 vendors, 1 vegetable vendor wished to opt-in while the others had reservations. After the completion of 2 weeks, upon observing the viability of the process and the benefits reaped by the vegetable vendor, the other 2 vendors wished to join the pilot.

Challenges Encountered

-

Hitches due to unfamiliarity with the technological aspect on the vendors’ side. Some amount of practice and assistance for them to fulfil their end.

- Lack of literacy among vendors: method of communication of orders was adapted to be through voice message for the same.

-

The regular price fluctuations in the pricing of the goods- due to the nature of these goods, i.e., agricultural products, there are fluctuations in price on a daily basis leading to discrepancies in the actual price at a given time and the advance payment made by the customer.

Conclusion

The pilot confirms that there is a dire need for an alternative source of working capital among street vendors. It validates that BharatBazaar can be that alternative. Additionally, it is demonstrated that the model is viable and offers a wide range of benefits to customers and vendors alike. There have been several attempts at providing low cost or no-cost loans to street vendors to help sustain their business, as mentioned above, but what sets BharatBazaar apart from the plethora of other solutions is that it has the potential to completely eradicate the need for street vendors to take loans in a hyperlocal manner. The model is also scalable; being based at a pin code level, it can be replicated across geographies. More study and pilots on a larger scale are the way forward to perfecting this model, ironing out its challenges and making it accessible to the large population of microentrepreneurs.

[i] Shrinidhi V – is a student of economics, currently pursuing her Grade 12, with deep interests in law, socio economics and policymaking.

All views are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Dvara Research.

References

WIEGO (December, 2020). COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy: Informal Workers in Delhi, India. Retrieved from: https://www.wiego.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-and-informal-economy-informal-workers-delhi-india

Bhowmik, K. S., Saha. D.. (September 2011). Financial Accessibility of the Street Vendors in India: Cases of Inclusion and Exclusion. Mumbai, India: Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Retrieved from https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Bhowmik_Saha_StreetVendors_India_UNDP-TISS.pdf

Nagaradona Vijayabhaskar, Dr.G. Arun Kumar. (2021). A Socio-economic Study on Financial Inclusion in India – Street Vendor Perspective. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt /Egyptology, 18(4), 5141-5151. Retrieved from https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/7094

Ananth, B.; Karlan, D.; Mullainathan, S.. (2007). Microentrepreneurs and Their Money: Three Anomalies. (n.p). Retrieved From https://sendhil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Other-Article-10.pdf

Cite this item

APA

V, S. (2021). Solving the Micro-Entrepreneurs Working Capital Conundrum: BharatBazaar Pilot. Retrieved from Dvara Research Blog.

Chicago

V, Shrinidhi. 2021. “Solving the Micro-Entrepreneurs Working Capital Conundrum: BharatBazaar Pilot.” Dvara Research Blog.

MLA

V, Shrinidhi. “Solving the Micro-Entrepreneurs Working Capital Conundrum: BharatBazaar Pilot.” 2021. Dvara Research Blog.