Update: This post is based on the provisions of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018. A new Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 was introduced in the Lok Sabha in the Winter Session of the Parliament in December 2019. However, this post is not affected as the provisions it is based on have remained unchanged in the new Bill.

Indian users are rapidly gaining more access to information and communication technology (ICT). Over 1168.89 million telecom subscriptions exist in the country, and internet usage is also growing steadily with more than 512.26 million internet subscribers (TRAI, 2018). India, today, is the second largest user of the internet and the second largest market for smartphones (Bhattacharya, 2018). The digital ecosystem data has the potential to increase the efficiency and speed in delivery of services and align the design of products with the users’ preferences. However, it can also render users vulnerable to a variety of new harms. This blog series introduces the reader to the different kinds of harms which can arise from the digital ecosystem and how the draft Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018 grapples with them. The first article in this series introduces some new harms facing users in the digital ecosystem that players in the Indian ecosystem must contemplate in order to build appropriate safeguards.

In 1993, Peter Steiner published a seminal cartoon in The New Yorker. The caption of the cartoon read, “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” (Fleishman, 2000) highlighting one of the key features of the internet – anonymity. Today this adage no longer seems to be applicable. As people spend more time online generating and consuming a high volume of data, they are creating digital footprints that are replete with their personal information. Consequently, the internet is transforming from being a passive interface between the user and the service provider to an active cache of information that service providers can tap into.

In 1993, Peter Steiner published a seminal cartoon in The New Yorker. The caption of the cartoon read, “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” (Fleishman, 2000) highlighting one of the key features of the internet – anonymity. Today this adage no longer seems to be applicable. As people spend more time online generating and consuming a high volume of data, they are creating digital footprints that are replete with their personal information. Consequently, the internet is transforming from being a passive interface between the user and the service provider to an active cache of information that service providers can tap into.

This has important implications for financial services. For instance, traditionally, a person seeking a loan would have to submit information such as name, employment status and financial details. Typically, the lender would assess their creditworthiness through their credit score, issued by regulated credit bureaus. The absence of a credit score could count against a potential borrower, despite other (non-credit scored based) indicators of the person’s repayment-attitudes and ability to pay demonstrated in their general behaviour. Today, digital service providers can overcome these limitations by understanding their customer better through their digital activity (Stewart, 2014). In the case of the same financial loan, by using the alternative, personal data of a prospective borrower, the lender can create a more comprehensive consumer profile to better gauge credit risk-associated with the borrower. In some instances, this enables lenders “to offer consumers new credit opportunities, and in other cases it might illuminate risk” (Experian, 2018). Alternative data typically includes payments of utility bills, telecom bills as well as data generated through social media platforms, as well as data passively collected by the digital credit platform such as browser history.

Given increased usage of ICT technology, such data is abundant. A quintillion bytes of personal data are generated every day on the internet (Marr, 2018) and data analytics has made it possible to ascertain a person’s identity and character by analysing their digital records (Kosinski, Stillwell, & Graepel, 2013). Several entities deploy data analytics to identify users, infer their financial details, health details, personal requirements, preferences, fetishes and quirks. When a user can be decoded in this manner, they also become more susceptible to harm. This article probes harms that may surface in the digital ecosystem.

The Indian Digital Ecosystem

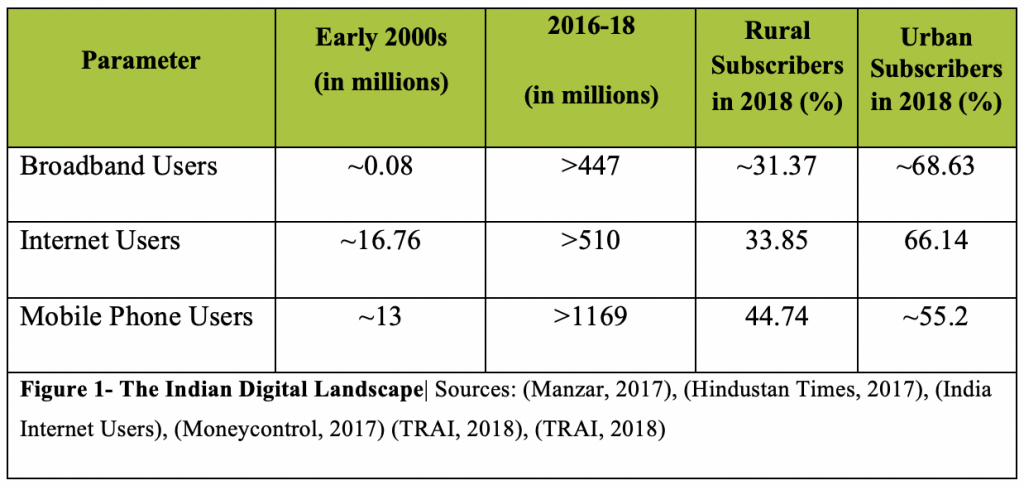

The Indian digital ecosystem also mimics global trends of increased data consumption, generation and internet access. The table shows a significant increase in broadband usage, internet usage and mobile phone usage, over the last two decades.

In addition to the increased usage of internet and mobile phone itself, more than 462 million people also use mobile internet (TRAI, 2018), (TRAI, 2018). Although these translate into a small fraction of the Indian population (Bhattacharya, 2018)—only ~33% of the Indian population uses the internet (Hindustan Times, 2017) and only ~22% of Indian adults own smart-phones (Bhattacharya, 2018))—India is the second largest user of the internet and the second largest smart-phone market in the world (Bhattacharya, 2018) generating enormous amounts of data: approximately 40000 petabytes every month (ETTech, 2018).

Indians are thought to be consuming 1 GB of data every day as opposed to 0.13 GB a day, one and a half year ago, on their smartphone alone (Nielsen, 2018), (CISCO, 2016). These numbers are expected to rise exponentially, considering, close to 50% of smartphone owners did not subscribe to data as of 2017 (Omidyar Network, 2017). In rural India, close to 58% (~513 million) people use mobile phones but only approximately 16% (~140 million) use the internet (TRAI, 2018) and less than 5% of adults own a smartphone (Omidyar Network, 2017).

If the penetration of ICT services is set to continue at a rapid pace, this also raises new concerns in the ecosystem. Users face a new variety of risks in this new world that demand the urgent attention of all stakeholders.

Harm & its Forms

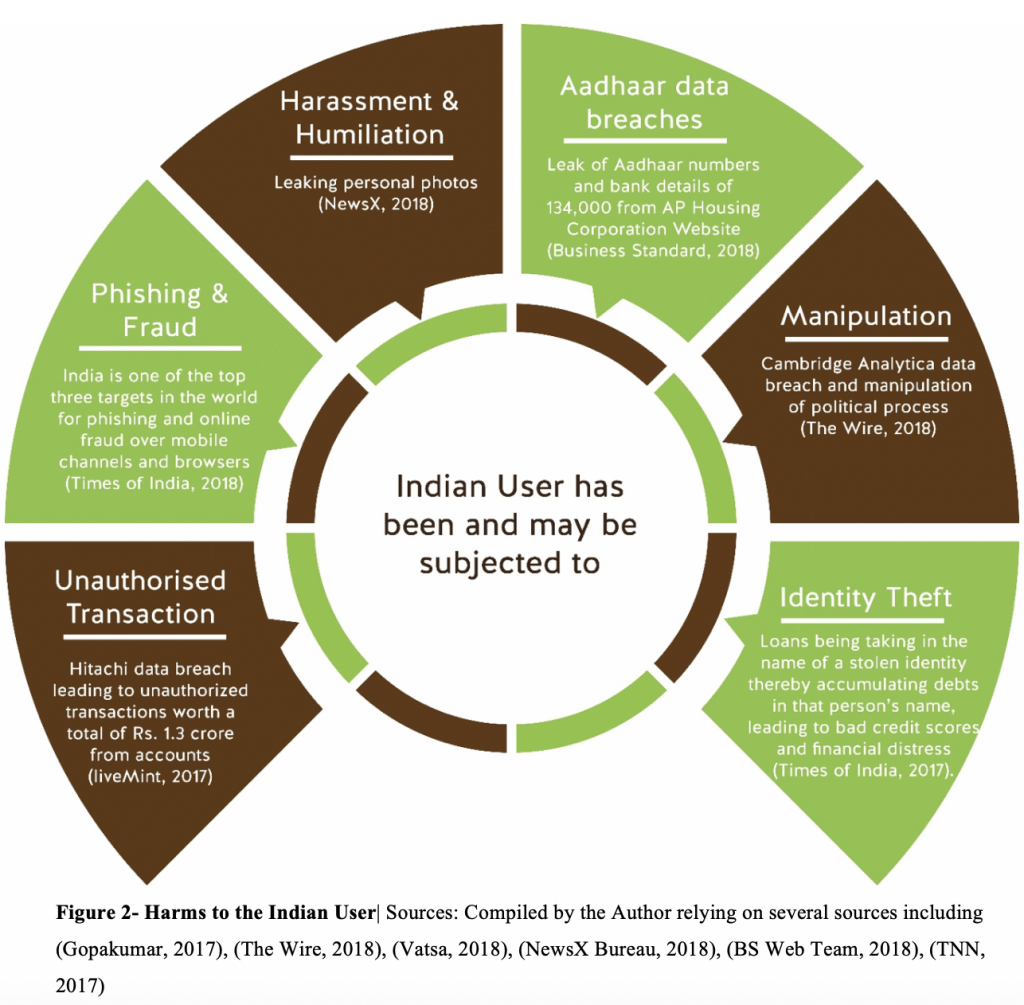

The increased use of personal data is creating new kinds of harms for the consumer, while also amplifying some of the existing harms. Our earlier work shows that privacy harms, identity theft, harms due to extreme differentiation and harms occurring from the use of untested algorithms are some new forms of harms emerging in the digital ecosystem (Chugh & Kumar, 2017). Over the last two years we have seen some of these harms materialise in India:

Figure 2, briefly illustrates some instances of the different kinds of harm which the Indian user has suffered in the past two years. In 2017, 3.24 million data records were stolen, lost or exposed in India. Close to 52% of Indians reported a data breach in 2017 compared to the global average of 36% (PTI, 2018). Estimates suggest that in 2017, India witnessed approximately 29 major data breaches (Khetarpal, 2018), while each data breach is estimated to cost close to 11.9 crore rupees (IBM & Ponemon Institute LLC, 2018). Unauthorised access to users’ personal data also leaves them vulnerable to a wide variety of immediate and advanced forms of harms. Other jurisdictions are grappling with some advanced harms from improper processing, such as the loss of employment opportunities, as in Robins v Spokeo, Inc (Robins v Spokeo, Inc., 2017); or discrimination by virtue of individuals’ social identity such as in the Amazon Prime Services incident (D. Ingold, 2016).

Our small, deeply qualitative primary research also led us to similar findings. In 2017, we set out to understand how people across different sections of the society in India valued their privacy over their personal data and if they felt prepared to tackle the new challenges presented by the digital ecosystem (Dvara Research, 2017). Our findings show that people value their personal data deeply and most respondents had suffered financial fraud through telephonic impersonation, while many others feared reputational harm. Participants were unwilling to sell their data in for money or privilege. Instead, they were willing to share their personal data if they were assured that no harm would be caused to them through it. They felt ill-equipped to understand and protect themselves from these new harms. Citing their inability to identify potential sources and forms of harms, participants pressed for responsible provider behaviour.

As the Indian digital ecosystem continues to grow at unprecedented levels, stakeholders must be watchful of these new challenges especially since many of Indians who will join the digital ecosystem will be from lower-income households who may be financially and digitally vulnerable. If the digital financial ecosystem is not created responsibly, these households could face unexpected financial shocks created by financial theft or phishing, which would disrupt their economic stability. This could set back their chances of integrating into the formal financial system (Medine, 2016); and may cut them off from various other vital services. These shocks could also dissuade users from using digital services (Medine, 2016) and limit their engagement with new channels of formal finance which have potential to improve their standards of living (Raghavan, 2017) (Omidyar Network, 2017). A dire need for protecting users from harm emerges from this scenario.

Identifying data-related harms

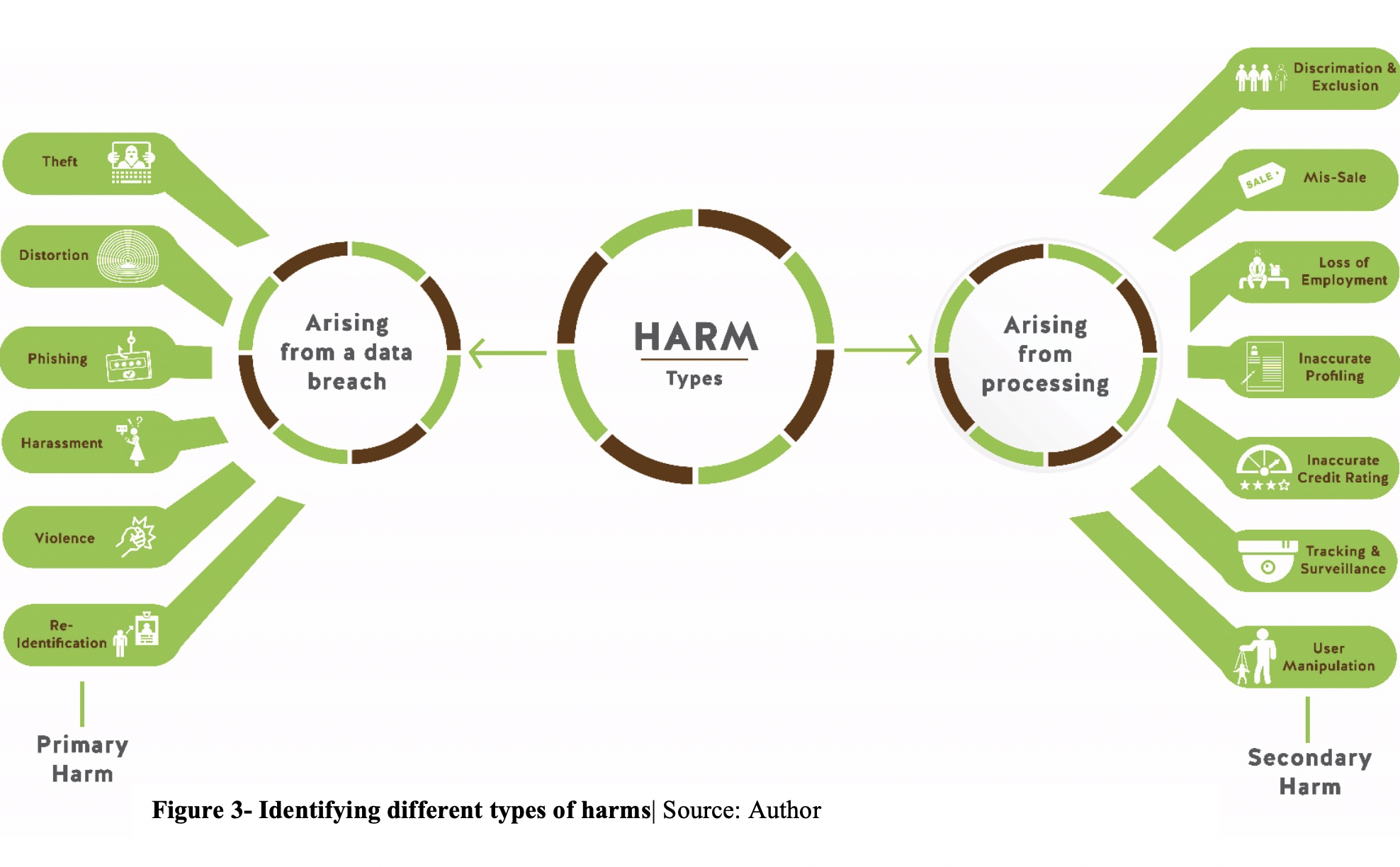

Identifying data-related harms poses a unique regulatory challenge since they are unpredictable and indiscernible. Typically, data harms may be caused after a user’s personal data is breached or when it is processed. When either of these events occur, it is difficult to ascertain when and how they would harm the user. Moreover, technological developments will continue to give rise to new varieties of harms, making a complete list of harms difficult to conceive of. Today, a breach of personal data increases the risk of identity theft, monetary theft, financial fraud or harassment (Kemp, 2017), blackmail and distortion of data (Solove, 2006). It may also cause physical violence against the user. Improper data processing can lead to inaccurate or discriminatory conclusions about a user’s traits which may result in their losing employment or their creditworthiness. It may also be used to manipulate a user’s behaviour online and offline (Kemp, 2017). Breaches and data processing can also be used for surveillance and profiling by private parties as well as the government (Solove, 2006). However, there is no way to know when and how any of these harms would materialise:

Therefore, though it is foreseeable that personal data can be used to cause harm to a user, the form of harm is indiscernible and unpredictable. Regulators must grapple with these issues when regulating harms.

Countries around the world have begun to take cognizance of this fact. More countries are enacting laws to regulate data processing and protect consumers (Consumers International, 2018).[1] The draft Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018 attempts to answer this call. The draft Bill, under section 3(21), defines harm elaborately- as including harms to person, property, reputation et cetera.[2] It builds also its regulatory structure around harm to the consumer which serves as a trigger for initiating regulatory action. However, this approach to defining harm and using it as a trigger may not be an effective solution for consumer protection. The next article will unpack the conception of harm under the draft Bill and illuminate some important concerns about the shortcomings of this approach.

—

References

- Bhatnagar, S. (2014). Public service delivery: Role of information and communication technology in improving governance and development impact. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Bhattacharya, A. (2018, June 21). India’s internet penetration is actually way lower than you’d think. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Quartz India: https://qz.com/india/1310947/india-ranks-last-in-pews-survey-of-internet-penetration/

- BS Web Team. (2018, April 26). Aadhaar privacy row: SC raps govt as 134,000 Indians’ data leaked; updates. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Business Standard: https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/aadhaar-data-of-134-000-citizens-leaked-on-andhra-govt-website-top-updates-118042600536_1.html

- Chugh, B., & Kumar, N. (2017, November 7). Harms to Consumers in Modular Financial System. Retrieved December 21, 2018, from Dvara Research: https://dvararesearch.com/2017/11/07/harms-to-consumers-in-a-modular-financial-system/

- CISCO. (2016). VNI Complete Forecast Highlights. Retrieved December 28, 2018, from CISCO: https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/m/en_us/solutions/service-provider/vni-forecast-highlights/pdf/India_2021_Forecast_Highlights.pdf

- Consumers International. (2018, May 25). The State of Data Protection Rules Around the World. Retrieved December 26, 2018, from Consumers International: https://www.consumersinternational.org/media/155133/gdpr-briefing.pdf

- Ingold, S. S. (2016, April 21). Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of its Customers. Should It? Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Bloomberg: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2016-amazon-same-day/

- Dvara Research. (2017, November 16). Privacy on the Line: What do Indians think about privacy & data protection? Retrieved December 12, 2018, from Dvara Research: https://dvararesearch.com/2017/11/16/privacy-on-the-line-what-do-indians-think-about-privacy-data-protection/

- ET Telecom. (2018, March 29). Data tariffs fall 93% in last three years: Telecom department. Retrieved from ET Telecom: https://telecom.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/data-tariffs-fall-93-in-last-three-years-telecom-department/63537339

- ETTech. (2018, August 17). Data generated in India throws a massive opportunity for startups: Amitabh Kant. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from ETtech: https://tech.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/people/data-generated-in-india-throws-a-massive-opportunity-for-startups-amitabh-kant/65442947

- Experian . (2018). The state of alternative credit data. California: Experian Information Solutions Inc.

- Fleishman, G. (2000, December 14). Cartoon Captures Spirit of the Internet. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from New York Times: https://web.archive.org/web/20171229172420/http:/www.nytimes.com/2000/12/14/technology/cartoon-captures-spirit-of-the-internet.html

- Gopakumar, G. (2017, February 10). Malware caused India’s biggest debit card data breach: Audit report. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from liveMint: https://www.livemint.com/Industry/jVF2Aw72w0DcBsUGseV0UP/Malware-caused-Indias-biggest-debit-card-fraud-Audit-repor.html

- Hindustan Times. (2017, October 1). In a rush to expand digital literacy, don’t forget to put equal stress on Internet safety. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Hindustan Times: https://www.hindustantimes.com/editorials/in-a-rush-to-expand-digital-literacy-don-t-forget-to-put-equal-stress-on-internet-safety/story-arxpXR7bCm58NeAOjpswIN.html

- IBM & Ponemon Institute LLC. (2018). 2018 Cost of a data breach study: Global Overview. Michigan: IBM.

- India Internet Users. (n.d.). Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Internet Live Stats: http://www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users/india/

- Kemp, K. (2017, August 22). Big Data, Financial Inclusion and Privacy for the Poor. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Dvara: https://dvararesearch.com/2017/08/22/big-data-financial-inclusion-and-privacy-for-the-poor/

- Khetarpal, S. (2018, May 28). Data theft increased by 783% in India in 2017, says study. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from Business Today: https://www.businesstoday.in/technology/news/data-thefts-increased-783-percent-india-2017-gemalto-breach-level-index-study/story/277905.html

- Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., & Graepel, T. (2013). Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. PNAS , 110 (15), 5802-5805.

- Manzar, O. (2017, December 16). A 15-year journey to bridge the digital divide. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from liveMint: https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/OvWHiB3AZmLx0k2ohkJACL/A-15year-journey-to-bridge-the-digital-divide.html

- Marr, B. (2018, May 21). How Much Data Do We Create Every Day? The Mind-Blowing States Everyone Should Read. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2018/05/21/how-much-data-do-we-create-every-day-the-mind-blowing-stats-everyone-should-read/#13606b3b60ba

- Medine, D. (2016, November 15). Making the Case for Privacy for the Poor. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from CGAP: https://www.cgap.org/blog/making-case-privacy-poor

- Moneycontrol. (2017, August 17). DATA STORY: How India has turned into the world’s second largest online market. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Moneycontrol: https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/technology/data-story-how-india-has-turned-into-the-worlds-second-largest-online-market-2362555.html

- NewsX Bureau. (2018, November 9). Akshara Haasan’s private photos leaked: Actor reaches out to Mumbai police and cyber cell. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from NewsX: https://www.newsx.com/entertainment/akshara-haasans-nude-leaked-actor-reaches-out-to-mumbai-police-and-cyber-cell-hot-sexy

- Nielsen. (2018, September 26). Average Indian Smartphone User Spends 4X Time on Online Activities as Compared to Offline Activities. Retrieved December 26, 2018, from Nielsen: https://www.nielsen.com/in/en/press-room/2018/average-indian-smartphone-user-spends-4x-time-on-online-activities-as-compared-to-offline-activities.html

- Omidyar Network. (2017, May 16). Currency of Trust: Consumer Behaviors and Attitudes Toward Digital Financial Services in India. Retrieved December 10, 2018, from Omidyar Network: https://www.omidyar.com/insights/currency-trust

- PTI. (2018, July 23). Data breach incidents in India higher than global average. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from The Economic Times: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/data-breach-incidents-in-india-higher-than-global-average/articleshow/65107118.cms

- Raghavan, M. (2017, December 23). The Privacy Judgment and Financial Inclusion in India. Economic & Political Weekly, LII (51), pp. 58-61.

- Robins v Spokeo, Inc., 867 F.3d 1108 (Ninth Circuit 2017).

- Sachitanand, R. (2018, October 21). All about India’s data localisation policy. Retrieved December 28, 2018, from The Economic Times: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/ites/all-about-indias-data-localisation-policy/articleshow/66297596.cms

- Solove, D. J. (2006). A Taxonomy of Privacy. University fo Pennsylvania Law Review, 154 (3), 477.

- Statista. (2018). Number of internet users in India from 2015 to 2022 (in millions). Retrieved December 11, 2018, from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/255146/number-of-internet-users-in-india/

- Stewart, J. (2014). Patent No. US 8,694,401 B2. United States of America.

- The Wire. (2018, March 29). What We Know and What We Don’t About What Cambridge Analytica Did in India. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from The Wire: https://thewire.in/tech/what-we-know-and-what-we-dont-about-what-cambridge-analytica-did-in-india

- The World Bank. (2018). Rural Population. Retrieved December 21, 2018, from The World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL?end=2017&locations=IN&start=1960&view=chart

- TNN. (2017, October 17). Identity theft: Fraudster applies for 7 loans. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from The Times of India: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ahmedabad/identity-theft-fraudster-applies-for-7-loans/articleshow/61109322.cms

- TRAI. (2018, November 28). Highlights of Telecom Subscription Data as on 30th September, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2018, from https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/PRNo114Eng28112018_0.pdf

- TRAI. (2018, October 3). The Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators April-June, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2018, from TRAI: https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/PIRJune03102018.pdf

- Vatsa, A. (2018, June 25). Phishing season: Cyber criminals have adopted innovative means to cheat people. Retrieved December 11, 2018, from The Indian Express: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/phishing-season-cyber-criminals-have-adopted-innovative-means-to-cheat-people-4576707/

[1]Also see UNCTAD, Data Protection Regulations and International Data Flows: Implications for Trade and Development, 2016 available at https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/dtlstict2016d1_en.pdf.

[2]Available at http://meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Personal_Data_Protection_Bill,2018.pdf