In the previous post of the blog series on financial depth, we attempted to understand the nature of the relationship between financial depth and economic growth. The natural question that follows is how to measure financial depth. This post answers that question by:

- Introducing various measures of financial depth

- Discussing the limitations of these conventionally used measures

Measures of Financial Depth

Early literature used the ratio of total bank credit to Gross Domestic Product (henceforth GDP) as the indicator of financial depth[1]. However, private firms are more likely to stimulate growth through their risk evaluation and corporate control capacities than credit to the government or state-owned enterprises[2]. Hence, ratio of domestic credit lent to the private sector to GDP has now emerged as the most commonly used indicator of financial depth of an economy. The private credit, therefore, excludes credit issued to governments, government agencies, and public enterprises. It also excludes credit issued by central banks[3].

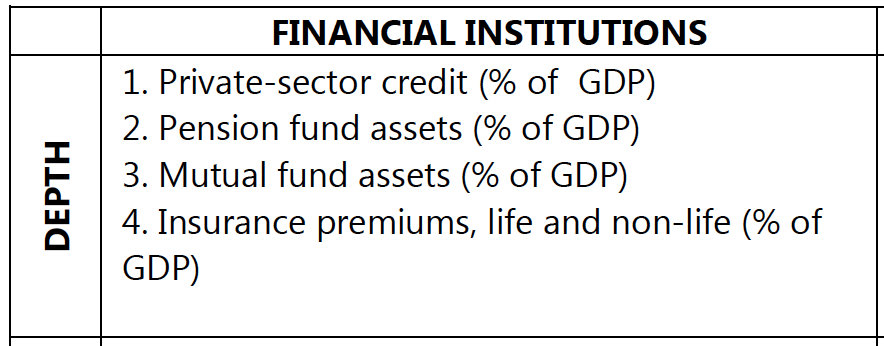

A recent research paper by the IMF outlines the various measures of financial depth[4]:

However, in the context of developing countries, it is reasonable to assume that pension fund, mutual fund and insurance markets are not adequately developed to be used as measures of financial depth. Therefore, private-sector credit-to-GDP has remained the most widely used measure of financial depth.

Limitations of a Credit-to-GDP Ratio as a measure of Financial Depth

The above discussed measures are not without their limitations. This section discusses why these measures are inadequate to understand excessive provision of credit within an economy. Given below are the major limitations[5]:

1) Ignores heterogeneity in credit demand across countries: These measures ignore that the demand for credit across countries varies with their levels of economic, financial and institutional development. The main drivers of this heterogeneity in demand across countries are differences in financial depth, access to financial services, use of capital markets, efficiency and funding of domestic banks, central bank independence, the degree of supervisory integration, and experience of a financial crisis.

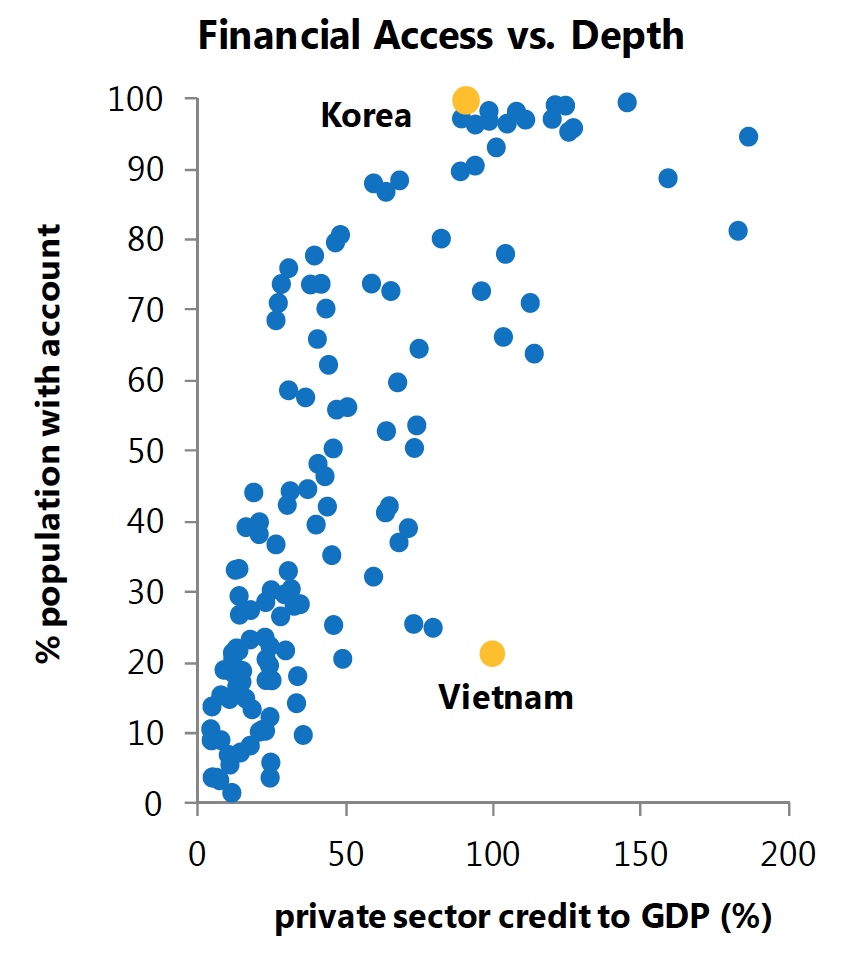

Figure 1: Bank Credit Can be a Misleading Measure of Financial Depth and Access – Korea and Vietnam have similar values of banking depth—a private credit to GDP ratio. However, they differ, by a large amount, in terms of access. The use of banking accounts is virtually universal in Korea, but in Vietnam only one-quarter of adults have a bank account.[6]

2) Assumes unit-elastic relationship between credit demand and income (as proxied by GDP) and price (as proxied by GDP Deflator): Depth indicators assume that a one-percent increase in GDP or the GDP Deflator results in a corresponding one-percent increase in the demand for credit. This assumption is violated, particularly for developing countries because of the varying usage of credit in economic transactions due to different levels of development.

3) Assumes that financial depth variables are stationary: A stationary variable is one whose statistical properties such as mean, variance and autocorrelation are constant over time. Credit-to-GDP ratio is empirically shown to be a trending variable, which means that credit grows considerably faster than the nominal GDP.

4) Fails to capture the effect of financial deepening at the sub-national levels: As conventionally used measures are constructed using readily available macroeconomic data, they are reflective of macroeconomic outcomes in financial deepening. In other words, they do not necessarily capture how well finance accomplishes various functions at various levels of the economy.

Consider the case of measuring financial depth in India where depth of financial services varies significantly amongst different regions. Ideally, the value of INR 1 of credit in a credit starved district should be greater than its value in a district which is relatively well-penetrated by credit. Inclusix published by CRISIL, which is an objectively measured index of financial inclusion provides a score for every district (out of 100), with 100 indicating a fully financially included district.[7] Scores in the index range from 96.2 for Pattanamthitta district in Kerala to a low of 5.5 for Kurung Kumey district in Arunachal Pradesh. This suggests that there is an inherent need for accounting for sub-national variations for one to appropriately measure the level of financial depth in an economy[8].

One measure of financial depth that does away with the limitations of conventional measures discussed above is ‘Equilibrium Credit’[9]. It is an important concept because it helps identify both excessive and deficient credit provision at sub-national levels of the economy. In other words, equilibrium credit helps to identify benchmarks against which the credit provision in various levels of the economy is judged to be excess or not. The next post in the series will discuss the idea of equilibrium credit in detail.

—

[1] King and Levine 1993. Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might Be Right

[2] Ibid

[3] Global Financial Development Report: Key Terms Explained. 2012. http://go.worldbank.org/E9RQKCP9J0

[4] Sahay et al. 2015. Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets

[5] Buncic and Melecky. 2014. Equilibrium Credit: The Reference Point for Macroprudential Supervisors

[6] Sahay et al. 2015. Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets

[7]Report, Committee on Comprehensive Financial Services for Small Businesses and Low Income Households. 2014, submitted to Reserve Bank of India. https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/PublicationReport/Pdfs/CFS070114RFL.pdf

[8] ibid

[9] Same as footnote 3