Israel has had a long-standing commitment to universal health coverage through government and non-governmental organisations providing prepaid healthcare services since before the State in 1948. National Health Insurance System covers all permanent residents, accounting for 98% of its resident population. At a total health spending of $2903 (PPP) per capita, Israel spends only a fraction of what most OECD countries do. Even with its relatively low spending, Israel’s health outcomes have been impressive in terms of preventing deaths, reducing loss of functioning and extending life, as evidenced by the low under 5 mortality rate, low DALY rate as well as high life expectancy, respectively (Table 1). What underlies these rather remarkable outcomes is a well-designed health system. In this post, we closely examine how the Israeli health system is financed.

Table 1: Health spending in OECD countries

| Country | Total Health Expenditure[1] | Govt. share[2] | Under 5-MR[3] | DALY rate[4] | Life expectancy[5] |

| Australia | $ 4,919 | 68.7% | 3.6 | 25598.6 | 83 |

| France | $ 5,274 | 83.7% | 4.5 | 27289.2 | 83 |

| Germany | $ 6,731 | 85.1% | 3.8 | 32162.2 | 81 |

| Israel | $ 2,903 | 64.8% | 3.7 | 19702.2 | 83 |

| Sweden | $ 5,754 | 85.1% | 2.6 | 26888.1 | 83 |

| Switzerland | $ 7,138 | 66.8% | 4.0 | 25581.3 | 84 |

| United Kingdom | $ 5,268 | 81.7% | 4.3 | 29324.8 | 81 |

| United States | $ 10,948 | 82.7% | 6.5 | 33866.3 | 79 |

Israel’s National Health Insurance System

The National Health Insurance System (NHIS) is based on the National Health Insurance Law of 1995, which made it mandatory for all resident citizens to join one of four official health insurance organisations (also termed sickness funds or health plans) with a nationwide presence (Table 2). These health plans are mandated to provide a standard benefits package to all residents who wish to enrol in their plan. There is an open enrolment period during which citizens can join a health plan, and these health plans are not allowed to reject any applicants. Citizens choose from among the four plans based on the network of hospitals and services they are offered and have the right to change their health plan up to two times a year.

Table 2: Health Plans and their changing market share

| Health Plan | Market Share (1995) | Market Share (2014) |

| Clalit | 63% | 53% |

| Maccabi | 19% | 25% |

| Meuhedet | 9% | 14% |

| Leumit | 9% | 9% |

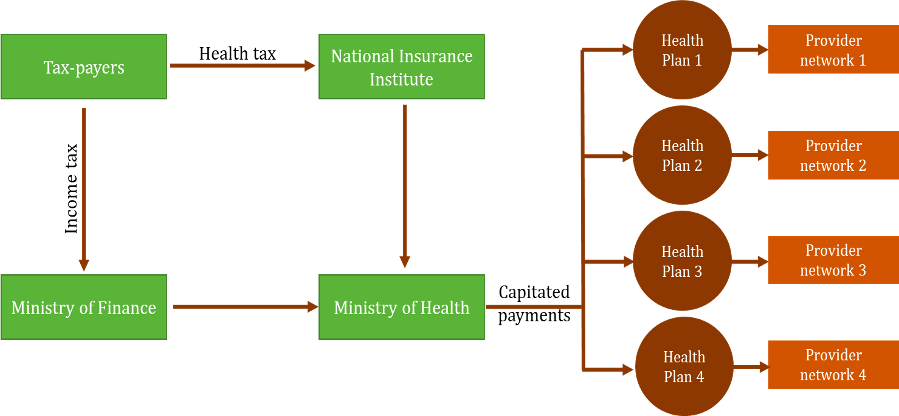

The NHIS is funded through a combination of general tax revenues as well as income-based tax collected solely for the purpose of healthcare (health tax). The pooled funds are distributed to the four health plans on a risk-adjusted[6] capitation basis, whereby plans were paid fixed amounts of money per patient per unit of time for the procurement and delivery of health services (Figure 1). This acted as an incentive for health plans to increase their membership irrespective of the amount of premium (tax in this case) paid by the customer.

Figure 1: Health financing flows under NHIS

Each of the health plans has exclusive contracts with providers. These arrangements can take different forms. For instance, the largest plan Clalit, owns hospitals and clinics, through which it provides care. Maccabi, on the other hand, contracts care from private clinics and hospitals that it does not own. The health plans also contract with general practitioners, most of whom are salaried employees of the plan. The remaining 5% of general practitioners contract independently with more than one health plan. Through the care networks they own/ contract with, the health plans provide a standard benefits package covering physician care, hospitalisation, diagnosis, medication, and in limited forms, dental care, and mental healthcare[7]. Just as health plans are not allowed to reject any applicants, healthcare providers are also not allowed to reject any patients. If a health plan refuses service, the insured can approach the Ministry of Health, which is the regulatory body. While the health plans receive capitated payments, the payments to providers/hospitals are through Procedure-Related Group (PRG) payments, where payments are made based on the principal procedure carried out. The Ministry of Health determines the maximum price lists for these.

Depending on the health plans, the gatekeeping role of primary care providers (PCPs) varies. In all health plans, visits to hospital-based specialists require prior authorisation, either from a PCP or a community-based specialist. However, in smaller health plans, members have unrestricted access to community-based specialists as long as they are affiliated with the health plan. In Clalit, in particular, given that it owns its hospitals and physician networks, PCPs play a much stronger gatekeeping role.

Unpacking the context

The NHIS provides a good case for a system that uses pooled funds to provide care that is effectively accessible, integrated, universal and at a minimal cost[8]. To better understand what worked and why, it is important to understand the context in which the health system is placed.

Much before the NHIS, the immigrant socialist labour groups established “Central European-style sickness funds” as mutual aid schemes that served members of the labour unions under the Jewish Labour Federation. This led to the rise of Clalit, which continues to be the largest sickness fund. While Clalit served unionised labour, other sickness funds emerged, focusing on non-unionised workers and upper-middle class professionals. Thus, when NHIL was implemented, 96% of Israeli’s were already voluntary members of various sickness funds. NHIS essentially coordinated the parallel systems of care in existence.

These sickness funds provided more than just a mechanism for pooling contributions. The influx of doctors migrating into Israel from Central and Eastern Europe, created provider networks, which were brought in by the health plans to provide care. Plans such as Maccabi and Meuhedet were, in fact, formed by physicians coming together to form health plans.

During the 1980s, the Israeli healthcare system was plagued by financial crises that led to growing dissatisfaction in Israeli society. There was a long-standing demand for healthcare reforms and universal healthcare that the Likud-led (Conservative) government sought to realise by introducing a compulsory national health insurance program. The law itself was heavily supported by the ministers of Finance and Health at the time. A combination of factors, including a rising dissatisfaction with the existing system, political will to address it and fall in the power of key players (Clalit), all ultimately led to the NHIL and subsequently the NHIS.

Conclusion

Even though a series of historical-socio-political factors played a significant role in the eventual design of the NHIS, the Israeli experience leaves key lessons for health systems design. For one, they were using pre-existing groups (unions in this case) as pooling and onboarding mechanisms which led to the expansion of insurance cover across the country. More importantly, with the early realisation that without care services to back it, healthcare financing is incomplete, and comprehensive systems of care were developed. Lastly, the robust IT-backed monitoring and review mechanisms helped the health plans to target objectives of cost, quality and equity in healthcare provision.

[1] Total Health Expenditure indicates the total health spending per capita (PPP) derived from multiple health financing sources like government spending, compulsory insurance, voluntary insurance and out-of-pocket payments.

[2] Government share indicates the share of government spending and compulsory health insurance in total health expenditure.

[3] Under-5 mortality rate is the number of deaths of children (below the age of 5) per 1000 live births.

[4] DALY rate is a measure of the burden of disease indicated by the number of years lost due to death or disability per 100,000 individuals.

[5] Life expectancy at birth indicates the number of years a new-born can be expected to live in a given country.

[6] As health plans are required to accept all applicants regardless of their risk category, the capitation paid is adjusted for such risks to avoid risk selection behaviour by plans. The capitation formula is based on the number of members and three risk adjusters – age, gender and place of residence.

[7] Although the NHI covers most basic services under the standard package, for accessing services not covered or supplementary services, these can be obtained through private funding- through out-of-pocket payments/ voluntary insurance/ commercial insurance.

[8] There is a co-payment element which requires a flat charge to be paid by the members for the first visit in the quarter (with exceptions).

References

Chernichovsky, D. (2009). Not “socialized medicine”–an Israeli view of health care reform. The New England Journal of Medicine, 361(21), e46. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMP0908269

Cohen, N. (2012). Policy Entrepreneurs and the Design of Public Policy: The Case of the National Health Insurance Law in Israel – Journal of Social Research & Policy. Journal of Social Research & Policy, 3(1), 5–26.

Gross, R., & Harrison, M. (2001). Implementing managed competition in Israel. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 52(8), 1219–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00241-0

Horev, T., Babad, Y. M., &Shvarts, S. (2003). Evolution of a healthcare reform: The Israeli experience. International Journal of Healthcare Technology and Management, 5(6), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHTM.2003.004247

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2021). GBD Results Tool. Global Health Data Exchange. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

OECD. (n.d.). Health resources—Health spending—OECD Data. OECD. Retrieved July 12, 2021, from http://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm

Rosen, B. (2011). How Health Plans in Israel Manage the Care Provided by their Physicians (No. 5). Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute. https://www.prhi.org/resources/resources-article/archives/monographs/90-monograph-5-manage-physician/file

Rosen, B., Waitzberg, R., &Merkur, S. (2015). Israel: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition, 17(6), 1–212.

Tulchinsky, T. H. (1985). Israel’s Health System: Structure and Content Issues. Journal of Public Health Policy, 6(2), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.2307/3342316

Waitzberg, R., & Rosen, B. (2020, June 5). International Healthcare System Profiles: Israel. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/israel#:~:text=Since%201995%2C%20Israel’s%20National%20Health,entitled%20to%20health%20care%20services.

World Bank. (2021a). Hospital beds (per 1,000 people)—Israel | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=IL

World Bank. (2021b). Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births)—Israel | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?locations=IL

Cite this item

APA

Nambiar, A., & Ashraf, H. (2021). Universal Health Coverage: Case Study of Israel’s Managed Care Model. Retrieved from Dvara Research Blog.

Chicago

Nambiar, Anjali, and Hasna Ashraf. 2021. “Universal Health Coverage: Case Study of Israel’s Managed Care Model.” Dvara Research Blog.

MLA

Nambiar, Anjali and Hasna Ashraf. “Universal Health Coverage: Case Study of Israel’s Managed Care Model.” 2021. Dvara Research Blog.