In this ongoing series, we will cover stories of citizens who have been excluded from social protection benefits delivered through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) and Public Distribution System (PDS). In collaboration with Gram Vaani*, a grassroots-level social tech company, we document the stories of beneficiaries who have faced challenges in welfare access in M.P., Bihar, U.P., and Tamil Nadu.

In this blog post, we explore a case of exclusion from the Public Distribution System (PDS), wherein a daily wage labourer, Mr. Kabeer, was unable to obtain a ration card for two months because he committed a procedural error while attempting to enroll. Instead of helping him navigate the enrolment process, local government functionaries continued to stall the enrolment, with the applicant running pillar to post in the absence of a robust grievance redress system.

One of the most fundamental points of exclusion can be found in the enrolment stage, which forms the first point of entry into the welfare system. Supply-side issues such as inordinate delays in application processing and lack of streamlined entry mechanisms have weakened the social security system. Exclusion from PDS can deprive the families reliant on it for their consumption needs. The speed and swiftness with which a beneficiary is onboarded into the scheme as a ration cardholder determines the efficacy of PDS as a social safety net. Many of the Central government’s COVID-19 related relief packages also primarily targeted ration cardholders[1]. Holding a ration card is also a prerequisite for other government schemes such as the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, making PDS a crucial part of a household’s safety net[2].

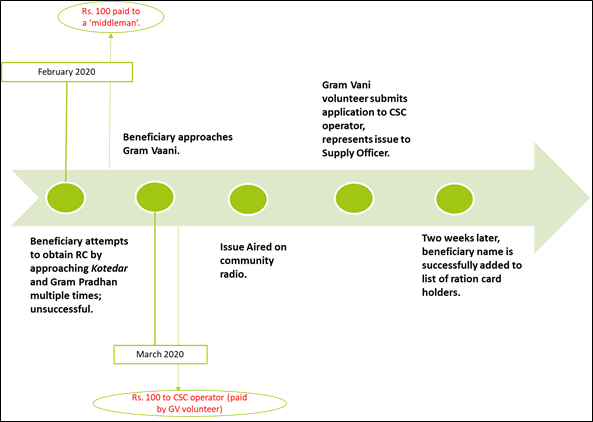

Mr. Kabeer from the Ghazipur district of Uttar Pradesh was out of work during the COVID-19 induced lockdown and was struggling to provide for his family. In February, he had submitted the written application form along with the required documents to the kotedar (a fair price shop officer) and the Gram Pradhan (head of village local self-government). On his multiple visits to the officials, his requests had not been entertained, and he was asked to return later. Unable to move the needle through government officials, he resorted to paying Rs. 100 to a ‘middleman’ who claimed that he could procure a ration card for Mr. Kabeer. However, the informal channel did not prove useful either. It was then that he approached Gram Vaani in the wake of increasing hardships due to the lockdown. According to the organisation’s volunteers, the process of obtaining a ration card in Uttar Pradesh is that the applicant must make an online application at the local Common Service Centre (CSC), and then submit proof of application to the local kotedar. The kotedar is then responsible for collating applications from his village and forwarding them to the block level for verification.

The Gram Vaani volunteer assigned to the case in April 2020 did exactly that to help Mr. Kabeer – he collected documents of Kabeer’s household members and accompanied him to the local Jan Seva Kendra to complete the online application form. The volunteer also bore the Rs. 100 application fees for the services of the CSC, as the family could not afford it. He then took this application to the kotedar and personally represented the case to the Supply Officer, a block-level official who provides a digital signature verification for all applications. Within a fortnight, the names of Kabeer and his family members were included in the list of ration cardholders at the Fair Price Shop (FPS). Airing the case on the community radio platform by Gram Vaani also helped put pressure on the kotedar – who took cognizance of the case only after media attention.

In our interview with the kotedar, he said that Kabeer had not submitted all the requisite documents and hence was told to return later. Without a civil society organisation to intermediate in this situation, the Gram Pradhan or kotedar should have informed the beneficiary of the correct method of application. The kotedar also noted that citizens preferred the online process as they believed it was faster. He also explained that unless the beneficiary explicitly reveals their preference, he cannot be expected to know which applicants are unable to navigate the digital application process. Since an application number was not generated in this case, the kotedar also had no way to follow-up with the applicant.

This issue would not have arisen if there was a better design of incentives in place for last-mile officials and more transparency/accountability in the system. It is key to the functioning of a scheme that information is extended to the citizen at the point of application – whether that be a Fair Price Shop, a CSC, or a panchayat-level official. While decentralisation is key to scheme implementation – in the absence of well-defined grievance redress systems – it does not solve the accountability problem for citizens. The case also demonstrates how exclusion can result from a combination of the beneficiary’s inability to navigate the system and the lack of official oversight. Such communication gaps create the need for intermediaries such as Gram Vaani and other civil society organisations that assist citizens in navigating their local enrolment/access points.

It is to be noted that neither the beneficiary nor the (ultimately successful) intervention by Gram Vaani employed an official grievance redressal mechanism. Either party may have lodged a complaint on Uttar Pradesh’s online grievance redressal portal, contacted the District Grievance Redressal Officer, or even called the toll free helpline number. We speculate that the beneficiary likely had limited knowledge of an official grievance mechanism, while the Gram Vaani volunteers figured they would be able to achieve resolution quicker through their tried-and-tested resolution pathways. In either case, official grievance redress is effectively non-existent: poorly publicised and lacking the trust of the broader public.

The case demonstrates the need for better accountability mechanisms to help citizens hold their local functionaries to task, and incentive structures to preclude such performance issues. As this series of case studies has repeatedly shown us, the effectiveness of social protection schemes can be directly compromised if implementation at the last-mile falls through.

Figure: Timeline of Exclusion and Costs Incurred

*The author would like to thank Pramod Varma from Gram Vaani.

A working framework to study exclusion in social protection has been employed to analyse this case, mapping points of exclusion across the four key stages of scheme design and delivery as detailed here.

[1] Ministry of Finance. (2020). Finance Minister announces Rs 1.70 Lakh Crore relief package under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana for the poor to help them fight the battle against Corona Virus. Retrieved from https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1608345

[2] Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana | National Portal of India. (2020). Retrieved 10 December 2020, from https://www.india.gov.in/spotlight/pradhan-mantri-ujjwala-yojana