Taking a portfolio approach to the balance sheet of Low-Income Household (LIHs), we see that these households, especially women, are offered ample opportunities to access loans and thereby add liabilities to their balance sheets. However, they are not yet provided with equally meaningful opportunities to build assets in their name, i.e., savings or investment.

Women play an active role in household financial management and are particularly motivated to save. Per an RBI field study report, of the four financial awareness metrics, i.e., financial literacy, knowledge, behaviours and attitude, women score low on the first three, especially knowledge, but score much higher in attitude, i.e., their outlook towards spending, saving and investing. Women are seen to make up for their lack of knowledge with a zeal to budget and save better. A relevant savings product that helps them accumulate an investment/savings corpus could be a powerful tool in building meaningful assets for these women.

In the following sections of this blog, we discuss the unique and complex financial lives of these households to set the context for product and process designs, delve into what a savings product for not just women but Low-Income Households (LIHs) in general could look like, and highlight some of the insights from various kinds of financial service providers on the challenges and opportunities in operationalising such a savings product for this segment.

Mind Over Money

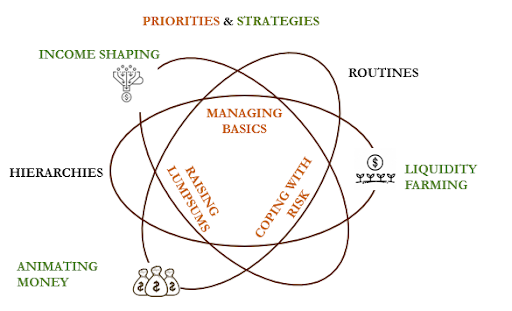

Building a truly relevant and meaningful financial product for LIHs requires a deep understanding and appreciation of their financial lives and money management practices. LIHs typically have income flows that are small, irregular, and unpredictable. Financial tools, notably savings, must adapt to their unique circumstances – insufficiency, instability, and illiquidity – to be of use and value for this segment. As detailed in The Portfolios of the Poor, LIHs have a somewhat ordered priority with regard to their money use:

- Managing basics: Cashflow management to fulfil their daily needs.

- Coping with risk: Building reserves or loan options that can help deal with emergencies.

- Raising lump sums: Building a corpus or loan options that can help seize opportunities to make big-ticket investments.

Given the erratic nature of their money inflows and outflows, the multiple things vying for their attention in an environment of scarcity, and the debilitating potential of any untoward contingency that befalls them, LIHs have complex financial lives that call for active and frequent money management decisions and actions. In this endeavour to meet their different priorities, LIHs are typically seen to deploy three strategies for managing their money:

- Income shaping: Cash flow management that strives to match irregular incomes with regular expenditures. This is particularly relevant for LIHs whose time of income is often varied or seasonal and whose surplus is so little that it requires active money management to make funds available for routine and non-routine expenses at the right times.

- Liquidity farming: Nurturing social and business relationships that can be called upon to provide liquidity in times of financial need. This requires investing time and energy in social and community pursuits that help build relations of mutual support and reciprocity.

- Animating money: Mentally compartmentalising different stores of money for different uses to avoid unwarranted spending of designated savings. Money is endowed with an economic, social, or moral purpose to aid the sustained accumulation of a lumpsum corpus.

LIHs deploy these strategies in different ways to optimise for their different money-use priorities. They use routines, i.e., scheduling regular expenses (ex, buying meat only on Sundays) and hierarchies, i.e., having a hierarchy of wants and needs to which different sources of money are directed (ex, unexpected windfalls go towards luxury purchases or money left over after all other expenses goes towards sweets and snacks).

Covering All The Bases

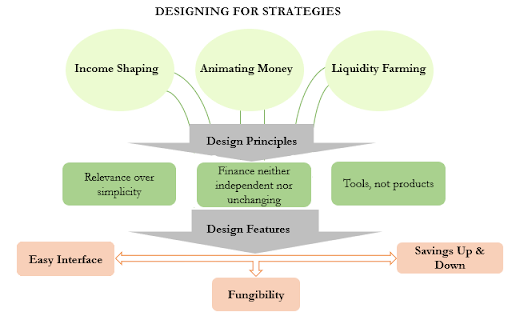

Most savings products in the formal market are designed for the priorities of LIHs and miss considering the strategies they employ to meet those priorities. However, while some formal products are amenable to one or two of the strategies (mostly income shaping and animating money), they fail to offer avenues for putting the third strategy of liquidity farming to good use. The fundamentally human aspect of social interactions and community investment is often not given due credence in most financial product designs (microfinance loans are a notable exception that uses social collateral to underwrite credit risk). Customers are viewed as individual economic actors living in an ecosystem devoid of network effects or relational dependencies. For LIHs whose lives are, on average, more precarious, it is a combination of these rational, psychological, and social strategies that make their complex financial lives manageable. Further, with their multiple contingencies and ambiguous financial flows, the goals and priorities of LIHs can often move across a broad spectrum of salience from immediate to fuzzy. This makes savings products with a narrow focus on priorities or boxed timeframes largely irrelevant to LIHs.

In coming up with a savings product for the low-income segment, the design principles of the Mas & Murthy framework explicitly acknowledge the complex, interconnected and varied life circumstances of this segment. These broad principles can then be filtered down to some characteristic product features that could make formal savings work for this segment.

Fungibility, i.e., the ability to use the same product for all three strategies, is a sought-after feature in financial products by LIHs. This aids in managing their day-to-day cash flow while also preparing for unforeseen emergencies and anticipated opportunities that come their way. Secondly, the ease of interface matters as much as the product features themselves. The subjective cost of access is often felt more immediately and acutely than the cost of product usage. Therefore, there is a preference for a single interface that provides multiple services as opposed to different interfaces for different financial services. Thirdly, LIHs value the ability to convert flows into stocks and vice versa. They look for nimble tools that provide the option to save up or down, as needed, over the entire product lifecycle. This helps them turn their variable cashflows into reliable sources of funds.

The popularity of ROSCAS, chit funds and flexible savings with local jewellers highlights the importance of multi-purpose, single-interface, dual-use products. The SHG model in the formal financial space offers some of these features. Still, it is limited by the priorities that apply to the whole group and does not allow for household-specific optimisation of resources.

The Product-People Fit

We know that bank-centric formal credit did not work for Low-Income Households (LIHs) in the Indian context, and the segment needed the MFI model to meet their credit needs formally. In the savings space, however, the emphasis is still on bank-centric formal savings. Unlike in the case of loans, where products were retrofitted in both their design and delivery to meet the unique constraints of LIHs, in the case of savings/investment, formal finance has not gone much beyond the government’s bank account ownership-based inclusion mandate.

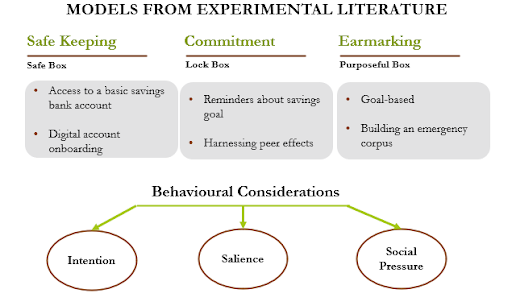

Research studies have experimented with different savings products with various add-on features to test inducement to regular savings. While some have been more successful than others, a lot seems to depend on contextual and individual factors. Some of the broad categories of experiments with savings products have been summarized below.

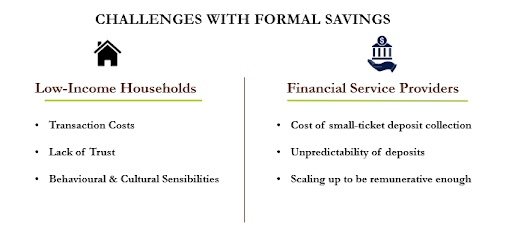

However, designing a successful and viable formal saving product for the low-income segment is famously tricky due to the multiple challenges on both ends i.e., the customers and financial service providers.

However, despite multiple challenges, we see that women from Low-Income households take pains to save and do so regularly. These are done via a combination of formal and informal means such as Jan Dhan accounts, SHG savings, local chit funds or jewel-based savings. Below is a non-exhaustive list of modalities through which LIHs save with an assessment of their upsides and downsides as an asset-building tool.

| Savings Channel | Upside | Downside |

| Jan Dhan Savings Bank Accounts | Basic safekeeping of money and transaction services | Not committed savings; Transaction and information costs |

| Self-Help Group (SHG) Savings | Group based peer effects promote longevity and commitment | Not household specific since a low means-based denomination is chosen as a savings amount by all group members; Could be exclusive |

| Local Chits/ROSCAS | Local leadership and social ties among members provide flexibility, induce commitment and eases savings up and down | Many are unregulated and some are fraudulent |

| Jewellers | Gold serves multiple purposes for women – as collateral, as a store of wealth that is held by them individually, as an inflation hedge, as easy liquidity during emergencies, etc. | High making charges |

We recognise that some of the informal means of savings will continue to make sense for this segment for a myriad of cultural, social, and contextual reasons. The formal market that prioritises the individual over the community and the absolute monetary balances over the relational equilibrium generated balances are at odds with the lived realities of the low-income segment. Product designs, delivery channels and servicing modalities need to evolve along with the necessary technology and a certain ability to think and imagine outside the traditional product management tropes.

However, instead of aiming to replace the existing informal means of savings, offering relevant means of formalising these savings that ensure the safety of capital and flexibility in transactions could help LIHs build assets in their balance sheets. This formalisation, while imposing some material and non-material costs on LIHs, also has the potential to reap net positive returns in terms of capital safety and access to better-priced credit. Unlike in the case of credit, where formalisation only leads to lower borrowing costs, suitable savings or investment products that earn some inflation-proof returns for low-income households will help them partake in the fruits of the country’s overall economic growth. Further, a well-designed savings tool that lets them exercise their existing money management strategies more effectively and efficiently can truly empower LIHs to meet their priorities and financial goals.

Path To Formalisation

For the formalisation of savings to be successful and meaningful, the design, delivery and pricing need to be on-par or better than what the informal market has hitherto offered to this segment. However, a profitable and sustainable formal savings product for the low-income segment takes a lot of work to operationalise for Financial Service Providers (FSPs).

In the last decade, some systemic shifts in products, players and regulations have made it conducive for a viable savings product to be made available for this segment. However, we have yet to see a successful model coming to the fore. With a plethora of FSPs, both digital and physical, now being allowed to act as conduits, there is merit in exploring how the overhead and other costs associated with servicing a savings product for LIHs could be brought down. By bringing the right stakeholders together at this opportune time, we could tackle more of the consumer constraints and optimise provider constraints to arrive at the right product feature mix that is relevant for LIHs and remunerative for FSPs.

Dvara Research conducted a roundtable to discuss the opportunities and challenges in achieving this goal with a variety of financial service providers , and the following are some of the key themes/viewpoints that emerged.

Operational Considerations

- Savings products for women, whether via digital apps or traditional financial service providers, need to be backed by an agent network. However, business correspondents earn minimally from just Cash-In-Cash-Out (CICO) services. Loan products cross-subsidise CICO to an extent.

- Savings products for women could work differently in different geographies, considering that particular state or district’s unique economic and social context.

- Micro-ATMs or ATMs that could enable CICO for savings products also have substantial operational costs involved in cash management, transit, and loading.

Customer Outcomes Issues

- Cashflow-based lending that does not consider existing loans and other financial liabilities of the household, both in the formal and informal space, might not be sustainable under stress. Savings can be part of a bouquet of financial services offered to households that strengthen their balance sheet.

- Savings linked to MFI loans can also be used for lender’s protection instead of customer protection when the features are skewed adversely against the customers. For instance, one month’s EMI in a savings account that is frozen for the loan period and adjusted against the last EMI is, in some sense, insurance for the lender rather than an asset for the customer. The bundled products’ features must be carefully considered to ensure optimal customer outcomes.

- The population to whom formal credit is currently made available is the segment that is most likely to be able to save through formal channels. We need to consider target customers and product design accordingly.

- Financial literacy programs provide financial knowledge that only helps them understand the products that they currently use. However, training to plan their finances so as to use a suite of different financial products tailored to their own needs and priorities would be more relevant and useful.

- Too much bundling can lead to poor customer outcomes when products that are cross-sold are not explained well to this segment or are inherently unsuitable to them.

Incentive Structures

- Loans and savings have become fungible for this segment with the easy availability of credit.

- There is little incentive to save with so many avenues for credit that are available for different needs, from retail and durable goods loans to personal loans and BNPL.

- There needs to be the right incentives to save – either as a loan option after a period of savings or interest rate concessions on loans for savers, etc.

- Products like chit funds (regulated entities) offer a means for households to save up and down as needed. It matches prospective savers with prospective borrowers while allowing them to choose when to save and borrow. In this case, savings become the primary activity against which borrowing is enabled.

- A standalone savings product might not be commercially viable for this segment. Considering the agent networks needed to sustain a savings product, bundling savings with insurance and loans could be a good option.

Regulatory Challenges

- Customer protection measures are often geared to the realities of the upper-income groups, and the same measures that protect these groups might lead to frictions or barriers for the low-income segment. For instance, ubiquitous PAN card requirements for investments in mutual funds impose a barrier on the low-income segment.

- Banks currently don’t differentiate between savers and non-savers while disbursing loans. The extra liquidity parked with the bank does not usually lead to interest rate benefits for the customers. Lower interest rates on loans for savers could be a good incentive for saving.

- Regulations need to consider the aspirations of the low-income segment and balance protective measures with measures aimed at enabling equitable and safe access.

Digital Solutions

- Digital payments have seen a marked uptick in recent years, which could signal expanding opportunity and relevance for digital savings products. However, moving from payments to savings and loans would be a steep learning curve for the low-income segment.

- A certain segment of low-income households has become digitally integrated and receive a significant portion of their income digitally. There is merit in exploring a digital savings product for this segment. Targeting such early adopters who would take up a digital savings product readily might help catalyse others in this segment to transition. Nevertheless, assisted models would be necessary in the early stages.

The second part of the blog is available here.