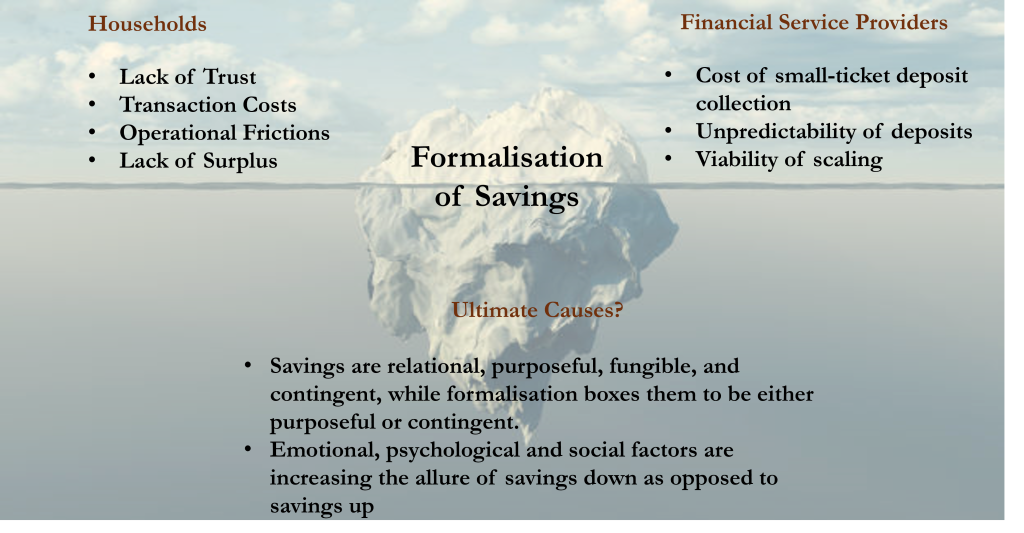

In the first blog in this series, we explored some mental models that Low Income Households (LIHs) employ in managing their money, described how current savings products are not attuned to these money management practices, and then discussed how products and processes could be reimagined to make formal savings relevant and meaningful for this segment. Our fundamental premise was that savings preferred by LIHs tend to be relational in nature, purposeful yet fungible by design and contingent upon various external factors. In contrast, formalisation tends to box them into just two categories – purposeful (goal-based savings in fixed deposits, recurring deposits, gold, etc.) or contingent (no-frills accounts that primarily act as a means to receive money). This, we argued, was one of the primary reasons for the low uptake of formal savings products among LIHs. In this blog, we delve further to uncover the institutional, cultural, and evolutionary factors underpinning the challenges of engendering formal savings among LIHs.

A Tale of Raja & Rani

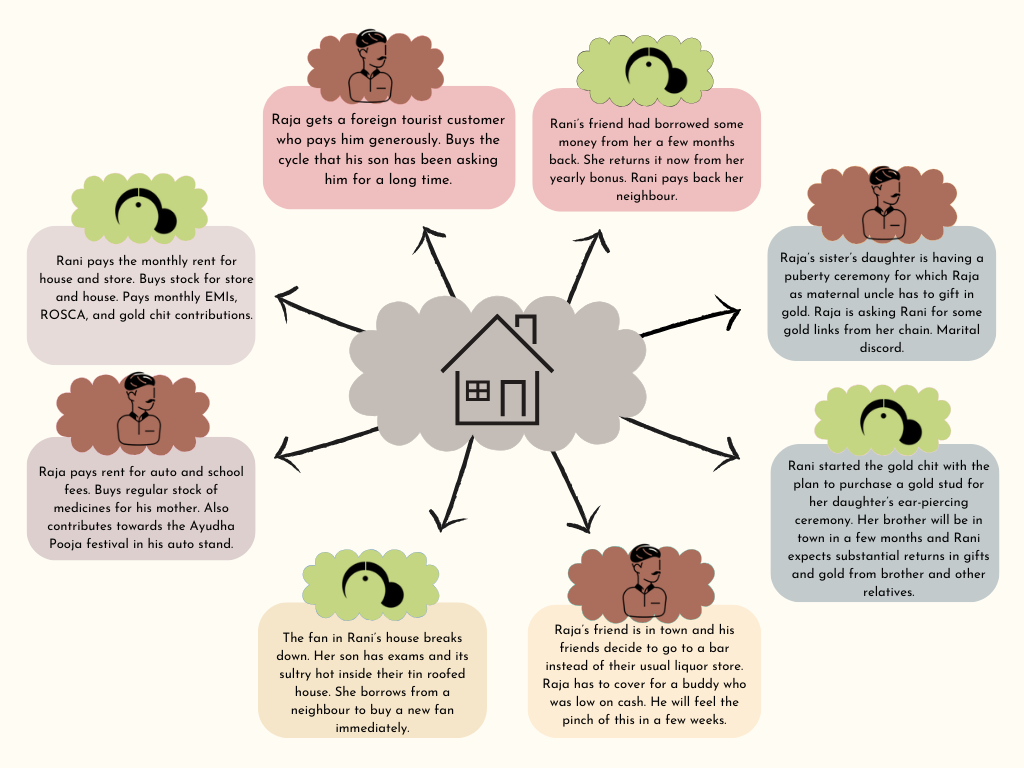

Before we go into the deeper contextual realm, let us revisit the relational nature of savings through a hypothetical case. In our story, a couple, Raja and Rani, live in a peri-urban town with their 10-year-old son, Ilavarasan; their 5-year-old daughter, Ilavarasi; and Raja’s 70-year-old mother, Kumudha. Raja drives an auto rickshaw, and Rani runs a small shop in front of their house; their annual household income is around Rs. 3 lakhs. As a dual-income household supporting three dependents, their savings through ROSCAs and gold chits are often insufficient, and they rely on formal and informal lenders to tide them over cashflow deficits. Raja has a married sister whom he feels responsible for, while Rani relies on her own brother to step up in times of ceremonies and other needs. As for the peer and social networks that influence their goals and aspirations, Raja’s friends from his auto stand and Rani’s friends from the ROSCA are people they draw parallels to. Furthermore, their relatives, neighbours, and popular culture, as reflected in the movies and shows they watch on TV, shape and cement their aspirations. Now, imagine that it is the first of the month, and consider the following scenario playing out in the lives of Raja and Rani.

This snapshot into the finances of Raja and Rani shows how, in the context of low-income households, spending and other financial decisions tend to be relational, and small aberrations carry high stakes. There are aspirations, faith, obligations and entitlements underpinning these financial transactions and they employ distinct money management strategies, as described in our previous blog, to help navigate the complexities inherent in their financial lives.

The Backdrop to Savings

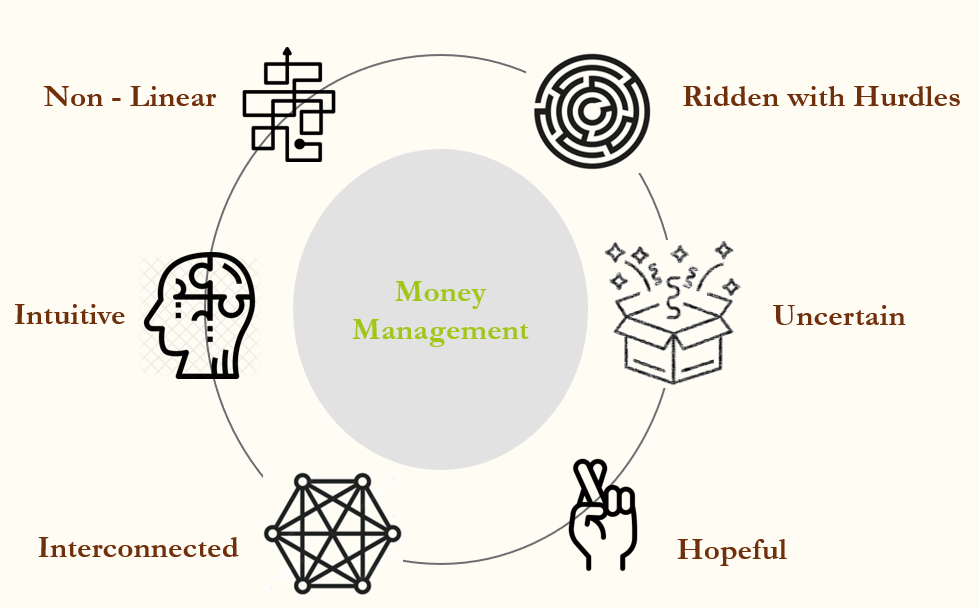

Now, let us set aside the context of LIHs and turn to understanding the factors that influence households to save. Literature often points to macro trends such as GDP growth, growth in disposable incomes, dependency ratios, levels of inflation and rates of interest to have a bearing on households’ willingness to save[1]. That is, a positive GDP growth and low levels of inflation that leads to a growth in disposable incomes along with low dependency ratios and high interest rates on savings creates an enabling condition for households to save[2]. Notwithstanding the truth in all these explanations, we hypothesize that there are deeper institutional and cultural factors that play a role in how households manage their money under any conditions and thereby their decision to save. We begin by using a cultural evolutionary perspective to understand the factors influencing how households decide to spend their money.

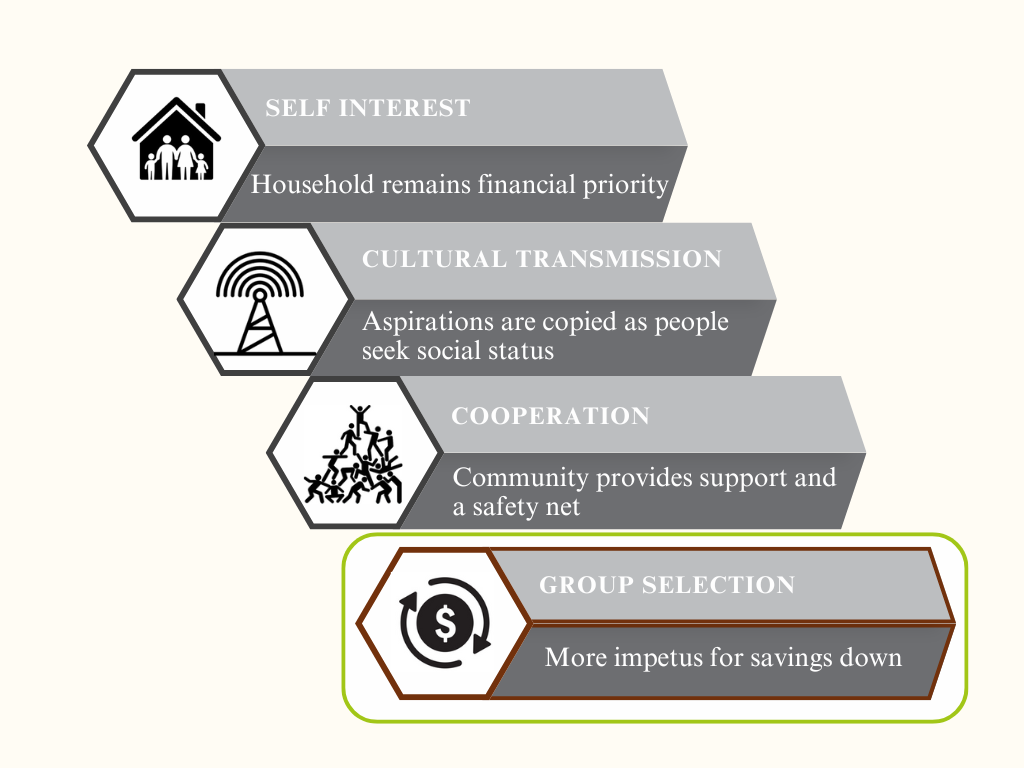

Let us take the four well-acknowledged factors that are found to drive the evolution of any culture[3], and see how they play out in the context of household finances.

- Self-Interest: The self-interest of the household and its members shapes financial decision-making. For instance, buying a house for the family and providing good education for the children remain financial priorities, regardless of the external circumstances at play. Here, household members are prioritised, and finances are optimised for the well-being of the entire household. Needs such as education and health, as well as aspirations like phone upgrades and entertainment, are sought to be balanced and meeting these needs and aspirations is constrained by factors such as income levels, price levels, and financing options.

- Cultural Transmission: Behaviours, beliefs, values and norms about money use are not independently determined by any household. Instead, they are cultural traits that diffused among a population. The prevalent zeitgeist acts to sanction or disapprove different kinds of financial behaviour, and cultural traits evolve in response to external circumstances. Some of these behaviours are transient and fleeting (such as an uptick in health insurance uptake post-pandemic), while others are more persistent (like saving in gold for a daughter’s wedding). The competition for status influences households’ perception of needs versus aspirations, and households mimic the aspirations of other households that are considered to have higher social status.

- Cooperation: Households are prosocial and often help one another even at a cost to themselves. Financial aid to (and from) friends and relatives in times of need is often taken as a given. Therefore, financial obligations and counter-obligations have a bearing on decision making.

- Group Selection: Households tend to coalesce into groups with similar levels of income, aspirations, and norms regarding money use, reciprocity and mutual aid. In fact, this tendency to group selection has been key to sustaining Self Helf Groups and Joint Liability Groups.

These four factors are not independent or iterative in any sense. Instead, they operate simultaneously and feed into one another to shape the financial decisions of a household. Understanding these four factors is important to understanding how changing contexts around inflation, stagnating incomes and easy availability of credit might act to pivot some of these forces to take a particular direction that might establish new norm or behaviour among certain sub-groups.

Here, we hypothesise that the pandemic and its subsequent social and economic consequences have acted as a watershed moment in history, setting ablaze a trail of events. There has been an inflationary pressure due to various micro and macroeconomic factors that are raising the cost of living while also stagnating disposable incomes and wages for the vast majority of population. Income inequality between salaried professionals and non-salaried workers has become immediately and perceptibly visible in how these different categories of population dealt with the economic shock that accompanied the pandemic. The RBI, in an effort to help the economy recover, had also kept the interest rate substantially low for two years after the pandemic. With such a backdrop, credit has come to be relatively easily available through different types of credit products from unsecured microfinance loans to hypothecated consumer durable loans. These contextual factors are neither usual nor insignificant. The starkly visible differences in lifestyles could propel aspirations with households looking to each other for social cues around spending, saving and money use. When meeting current needs and wants takes center stage, ideas around financial prudence, caution and discipline take a backseat, especially when aggressively marketed credit like personal loans, buy now pay later products, instant digital loans and consumer durables financing becomes ubiquitously available. In fact, the RBI’s Financial Stability Report of June 2024 highlighted falling savings and rising debt of Indian households post the pandemic. Together, they may have acted to turn the four different levers of self-interest, cultural transmission, cooperation, and group selection such that saving-down (through loans) to meet immediate needs and aspirations is prioritized, as opposed to saving-up for future needs and aspirations.

Normalisation and Routinisation of Debt

For those who have selected themselves into groups that rely on savings-down rather than savings-up, debt may have come to play an integral role in their money management. It seems to be used not only to make businesses investments or build assets, but also to meet cash flow deficits and fund aspirational lifestyle choices.

One way to understand how debt is used by these households is to apply the theory of ‘Ordinary Consumption’[4], which states that certain types of consumption (such as water use) are not a meaningful practice on their own. Instead, it serves as a resource for other meaningful practices (such as cooking or bathing). The provision of infrastructure for these kinds of ordinary consumption (such as a piped water supply in this example), can shift ideas of what constitutes a normal level of anything (the cleanliness of daily baths) and increase the legitimacy of usage by de-linking it from any moral decision-making (washing utensils under running tap water). This can be thought of as normalisation of debt by de-stigmatisation and changing its meaning. That is, debt becomes desirable, and high levels of its usage carry no moral burden or social stigma.

The creation of an infrastructure for accessing debt readily and easily (as pipelines would automatically provide water) would then act to make debt a routinely used tool for money management. The various sources of debt available to households help create a reliable and steady supply of debt such that it becomes a good of ordinary consumption.

Furthermore, debt, when it becomes ‘ordinary consumption’, creates a need or aspiration for other meaningful things, such as high-quality education, top-end phones, status goods, etc. This is not to pass judgment on whether LIHs should or shouldn’t have these needs and aspirations, but to recognise that when debt becomes central to money management, as it does when it becomes a good of ‘ordinary consumption’, it has the proclivity to shift the levels of what is considered normal or acceptable.

What Does This Cultural Group Selection and Debt Normalisation Mean for LIHs?

Debt is neither inherently good nor bad. It is only as good or bad as what individuals and households make of it. How households utilise debt depends to a large extent on their attitudes, behaviours, and norms. Now, if debt is routinised for households, i.e., supply is ubiquitous and easy, this provision of debt, over time, can influence attitudes, behaviours and norms (just as piped water supply changes norms around cleanliness and attitudes and behaviours towards water use for various activities).

Let us now use the example of video game design to tease out some of the pathways through which the provision of debt can create sticky habit patterns for LIHs. There are four widely recognised design patterns that make certain video games highly addictive[5]. We will draw parallels between these design patterns and microfinance loans that are offered to LIHs to see how cultural group selection and debt normalisation can create pathways for long-term behavioural changes:

- Group Formation: Just as many popular video games allow group play that induces community participation and peer group solidarity, microfinance loans create groups where there is peer pressure to participate alongside a feeling of oneness.

- Randomised Variables: In many popular video games, players start at different points with different types of arsenals, tools or weapons that are randomized. This makes one think that even if they were to lose this game, starting another game means a fresh start with the possibility of starting with better initial circumstances. Microfinance borrowers from low-income households typically face a higher incidence of contingent risks, such as job loss, income loss, health events, etc., and therefore start their debt journeys differently each time. So, despite current difficulties, if they finish paying this debt, the hope is that the next loan could be started in better circumstances leading to better gains. This is akin to gambling on better future circumstances.

- Repeatable Loops: Addictive games usually have repeatable game patterns that provides a sense of familiarity and predictability to players. Microfinance loans follow a standardised group recognition, assessment and training process that acts to provide similar positive reinforcement to borrowers.

- Loot Boxes: Some of the most addictive games have some kind of loot box at the end of the game that provides the player with ammunition to start a new game. Microfinance loans typically ensure that borrowers, if they finish paying a current loan, are given another loan that acts like a reward system, keeping borrowers engaged.

Just as these design patterns in video games are geared towards player engagement rather than winning or ending a game, microfinance loans could inadvertently keep borrowers reliant on these loans for their money management.

However, not all video game players are addicted to video games, and similarly, not all borrowers form an unhealthy reliance on loans. Personal susceptibility, substance addictiveness and environmental factors play a big role in addiction formation[6]. Here, low-income households are particularly susceptible due to their low levels of wealth, unstable and insufficient incomes, and lack of safety nets. Also, the infrastructure providing debt to these households is quite capable of engendering reliance as we discussed earlier. Further, the larger backdrop where LIHs are more likely to select themselves into social groups where there is a greater impetus to savings-down means that the environmental factors abetting habitual debt take-up are ripe. These together pose a significant risk for LIHs to easily become over-indebted or over-reliant on debt for their cashflow needs, thus creating an unfavourable environment to save-up.

Balance Between Savings-Up & Savings-Down

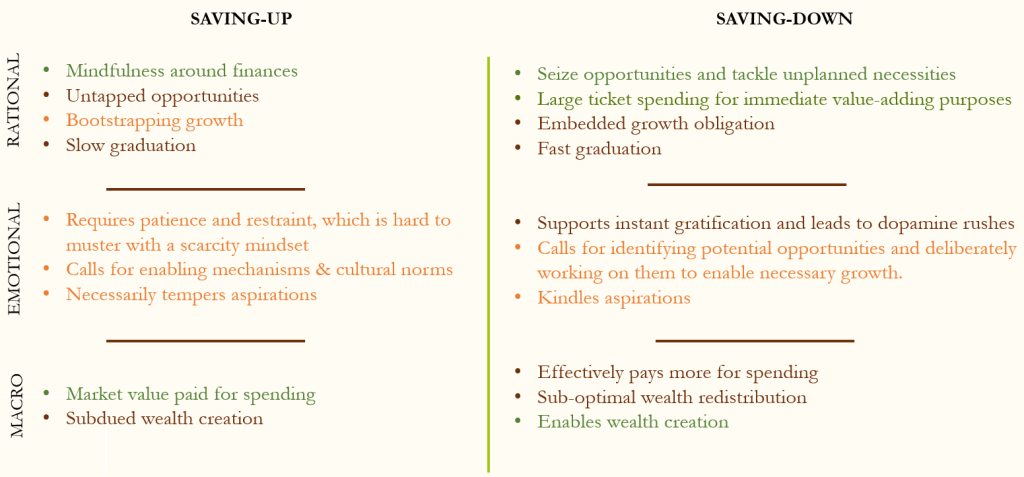

Both savings-down and saving-up have their fair share of pros and cons and work differently for different people in different circumstances. We list some of the rational, emotional and macro considerations around savings-up and savings-down to understand their differential impact[7].

An over-reliance on just one of these instruments could therefore lead to potential losses – in money, opportunities and social prospects. Harking back to our previous example, if money management were to be imagined as game, the game strategy would then be to find a balance between risking lives to gain coins (viz opportunities and time offered by debt for wealth generation) and securing gained coins (viz. wealth protection offered by savings). This calls for the careful construction of a portfolio of both debt and savings that takes account of households’ circumstances, prospects, capabilities and aspirations.

Why Formalise?

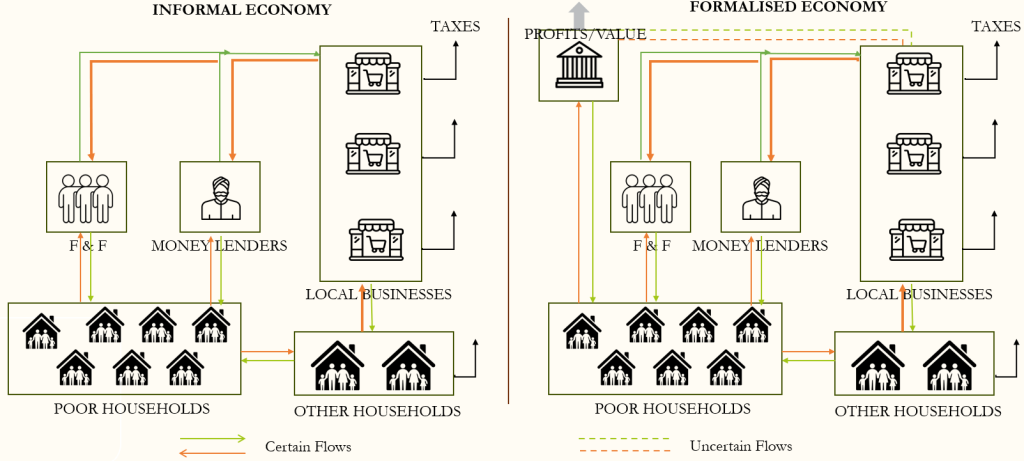

While we have attempted to make a case for why savings need to be considered in the context of debt, it does not mean that LIHs are currently not saving at all. Despite the downward trend, savings is still seen to be prevalent among LIHs, particularly in informal instruments such as Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs), chit funds, gold, etc. Given the relational nature of their current savings and the lack of suitable products in the market for formal savings, one can question the salience of formalised savings for this segment. Afterall, if one ventures beyond partial equilibrium models, there are some downsides to formalisation for this segment.

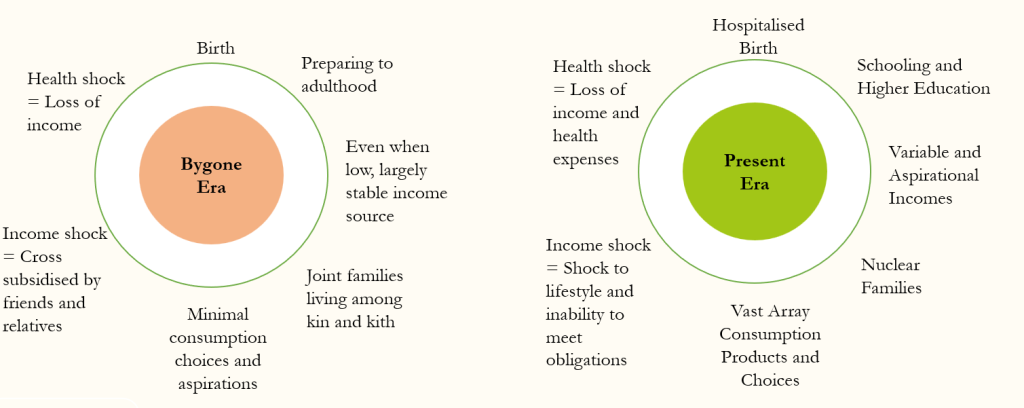

While money, value addition and therefore profits largely tend to circulate within the local economy in an informal setting, a substantial amount of value addition and profits tend to leave the local economy in a formalised setting. This might have repercussions for long-term equitability and geographical disparity. Nevertheless, formalisation becomes important and essential due to the distinct dichotomy between the old and new ways of life that informal economy is unable to bridge.

Informal savings that is community-linked, ceremonially mediated and time-agnostic might be incompatible with the new life cycle that is heavily financialised, market-oriented and has definitive time frames. In fact, some of the earliest literature on the financialisation of everyday life[8] highlights how this mismatch between the old and new ways of life could create a situation where credit steps in to fund all aspects of life. This might be unsustainable for a substantial majority of households who do not have high enough returns to capital to justify the interest payouts. Furthermore, it might possibly entrench cultural path dependencies of the sort we describe in this blog that might be sticky and hard to overcome in the future. Hence, it is crucial to provide households with meaningful and relevant formal savings products that not just recognises the relational nature of savings but also counteracts the pull of debt.

A Model Tool – One Account To Rule Them All

In this concluding section, we present a model savings tool that optimizes for all the strategies and priorities of low-income households, engenders community participation and peer effects, and provides options to save-up or save-down as needed. It uses different types of sub-accounts linked to one master account to help household optimise their savings and borrowing decisions.

- Gulluck(s): Sub-accounts that mimics a traditional money pot that is geared towards purposeful savings. It can have features like hidden balance information to weave in the element of surprise that LIHs seem to value while also incorporating nudges to save regularly or creating frictions to withdrawing from the account.

- Dabba(s): These sub-accounts reverse engineers an envelop based budgeting model but unlike envelopes that designate purpose and enforces limits, the dabbas here are non-committed savings that can either be purposeful (say for health, education, TV purchase, etc.) or open-ended (say for an emergency corpus). It can also include behavioural nudges to save in the form of reminders.

- Nidhi(s): Joint sub-accounts that tries to model a ROASCA, chit group or SHG savings by enabling members to come together to build a common corpus. This corpus could be earmarked for a purpose (say, Ganesh Chaturthi Festival in an apartment society) or open-ended (just a form of group-based savings). This account could have options for lending to members at agreed interest rates and act as a split-wise account for group savings.

Importantly, all three types of sub-accounts should provide customers with the option to name these accounts so that they have the functionality to animate and personalise different stores of their money.

Given current technological possibilities with Account Aggregators and the growing usage of digital payments among all segments, a savings tool of this can will probably find its relevance first among the middle-income segments. But as common in most technology diffusion, it is very likely to find its suitable place among the low-income segment over time. Such carefully designed and operationalised formal savings tool that complements and supplements formal debt can help LIHs balance the assets and liabilities of their household portfolio and still manage their cashflows optimally.

The first part of the blog is available here.

Footnotes:

[1] Athukorala, Prema-Chandra, and Kunal Sen. “The determinants of private saving in India.” World development 32.3 (2004): 491-503.

[2] Samantaraya, Amaresh, and Suresh Kumar Patra. “Determinants of household savings in India: An empirical analysis using ARDL approach.” Economics Research International 2014.1 (2014): 454675.

[3] Waring, Timothy M., et al. “A multilevel evolutionary framework for sustainability analysis.” Ecology and Society 20.2 (2015).

[4] Pellandini-Simányi, Léna, and Zsuzsanna Vargha. “How risky debt became ordinary: A practice theoretical approach.” Journal of Consumer Culture 20.2 (2020): 235-254.

[5] Schüll, Natasha Dow. “Addiction by design: Machine gambling in Las Vegas.” Addiction by design. Princeton university press, 2012.

[6] Chung, Sulki, Jaekyoung Lee, and Hae Kook Lee. “Personal factors, internet characteristics, and environmental factors contributing to adolescent internet addiction: A public health perspective.” International journal of environmental research and public health 16.23 (2019): 4635.

[7] The colouring of the different factors are subjective and based on the authors perspective on whether the factors are positive(green), neutral(orange), or negative (maroon).

[8] Pellandini-Simányi, Léna. “The financialization of everyday life.” The Routledge handbook of critical finance studies. Taylor & Francis, 2020.