This post is the third in a series where we seek to create intuitive and comprehensive consent artefacts for constrained customers in the RBI’s Account Aggregator (AA) framework. So far, we have discussed literature on why customers, especially constrained customers, are unable to give informed consent in a loan transaction. This post presents design elements that providers can use to make their consent artefacts more effective for constrained users. These design recommendations emerge from the insights from an immersive behavioural field study we conducted with 60 constrained customers through a gamified simulation of an AA transaction.

- Introduction

An Account Aggregator (AA) helps customers share their financial information with prospective lenders. The AA can share this information only with the customer’s explicit consent i.e., free, informed, specific, and revocable consent (Reserve Bank of India, 2016; Reserve Bank of India, 2022).[1] However, the consent customers give rarely meets this standard in a loan transaction. This is usually attributed to customers being unable to comprehend the language of the artefact or the artefact being too long to retain customers’ engagement. But the problem becomes more nuanced when it is examined from a behavioural lens.

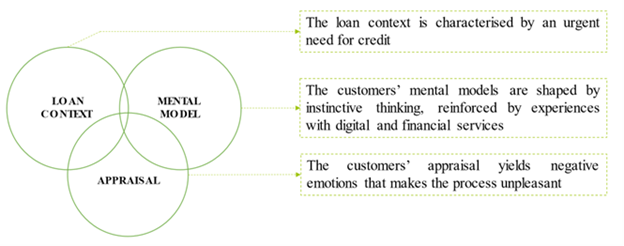

Taking a behavioural lens shows us that customers defer to making consent decisions passively i.e., they give the consent artefact a cursory glance and are pre-programmed to accept it, even without reading it or engaging with it. In the previous post in this series, we discussed three factors that make customers do so in a loan transaction (Figure 1). Broadly –

i. The urgency created by the larger loan context rushes customers towards giving consent without taking the time they may need to consider their decision.

ii. The customer’s mental models about consent, such as not having effective choice in giving consent to the lender because of the take-it-or-leave-it nature of the consent artefacts, power asymmetries with the lender, beliefs that active engagement will have no impact on the loan outcome, or other reasons. These mental models make customers think that actively engaging with consent artefacts is unnecessary and redundant.

iii. The customers’ appraisal of the consent artefact (i.e., their evaluation and emotional response to the consent artefact) makes them feel unpleasant because of its length, complexity and technicality. This unpleasantness makes customers want to disengage and exit the process (Gantayat, Ashok, Chugh, & Prasad, 2022).

Figure 1: A customer’s consent decision takes place at the intersection of three factors.

Using this decision-making framework, we set out to conduct a behavioural study with constrained customers. The study helps appreciate (i) the different factors that affect customers’ consent decision-making process in the AA context, and (ii) the potential behavioural solutions addressing these factors. The hypotheses for the study, methodology, and findings are set out below.

- Hypotheses explored in the study

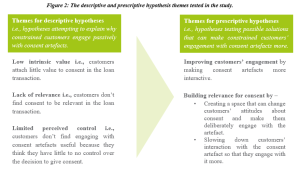

Our hypotheses explored five themes drawing from our literature review and insights from stakeholder immersion. The five themes include three descriptive themes and two prescriptive themes (Figure 2). The descriptive themes attempt to explain why constrained customers engage passively with consent artefacts. The prescriptive themes explore solutions to the challenges captured in the descriptive themes and, therefore, emerge from the descriptive themes.

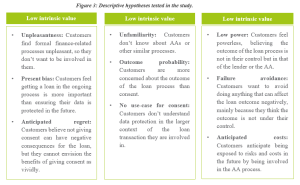

Each of the descriptive themes lend to granular hypotheses that try to explain what makes consent less valuable, less relevant, or less useful for constrained customers. These hypotheses build on different behavioural and cognitive factors set out in Figure 3.

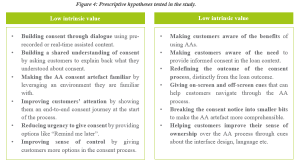

Similarly, the prescriptive themes lend to hypotheses exploring different solutions to improve customers’ engagement with AAs and make the AA process more relevant to them (Figure 4).

- Sample & method for the study

We conducted the study with 60 constrained customers. All the participants came from households in Kasmanda (rural cohort) and Sitapur (semi-urban cohort) in Uttar Pradesh, and Mumbai (urban cohort) in Maharashtra. The participant households earned annual incomes between 2 lakhs and 5 lakhs. Most of the participants used digital financial services and had experience with facing or hearing about digital financial fraud. Less than half of the respondents had experience with credit (formal or informal).

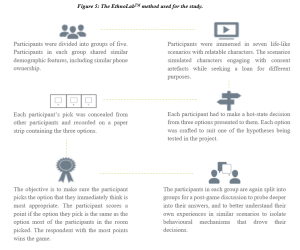

The study was conducted using the Final Mile’s proprietary research method, EthnoLabTM . The EthnolabTM is a gamified simulation of different contexts in which researchers can capture the behavioral barriers and enablers of participants’ decision-making (Figure 5).

The EthnoLabTM situates participants within decision-making scenarios mirroring real-time decisions that are relevant for a given problem statement. The participants are incentivised to respond instinctively and with the response they think the other participants are also likely to give. The Final Mile team created a bespoke EthnoLabTM set-up for this study, comprising seven life-like scenarios or simulations. Across simulations, characters are required to engage with AA consent artefacts while seeking a loan for different purposes. The context of the simulations and the archetypes of the characters were carefully crafted to ensure the respondents of the study found them relatable.

- Insights from the study

The study provided in-depth insights into how participants made decisions when interacting with the consent artefact. The detailed quantitative results from the EthnoLabTM study will be available here. Our insights in terms of insights relevant to the AA consent decision-making process are set out below.

4.1. The context for consent decision-making.

The context in which participants must make a consent decision is marked by –

-

An urgency to get their loan approved.

Participants’ decision to give consent is heavily influenced by this urgency. They believe that giving consent quickly would guarantee their loan approval. As a result, they don’t actively think twice about it. -

A sense of obligation to give consent. Participants associate the word ‘consent’ with a lack of choice – as something they must give the provider as a necessary procedural step. Participants associated the word ‘permission’ with more agency.

-

Unfamiliarity with the AA which breeds mistrust in the process and increases participants’ perception of risk.

-

Uncertainty in making trade-offs between the risks and benefits of giving consent through the AA.

4.2. Participants’ mental models influencing the consent decision.

The participants’ mental models or beliefs are anchored in their previous digital experiences (banking and non-banking). Participants create thumb rules to help them make decisions in the loan transaction including the consent decision through the AA.

For example, they take the mere presence of consent artefacts, terms and conditions, and privacy policies as a proxy for the app being safe. As a result, participants bypassed reading the consent notice. Participants also distrust online processes because of awareness and suspicion around digital frauds. Many worry that they would not find recourse when they need it the most, making them prefer offline processes to digital journeys. Further, participants trust financial institutions and entities with high brand recall to keep their data safe. This is thorny because we often found a gap in the participants’ perception of how their trusted institutions treated their personal data and the institutions’ stated data protection practices.

4.3. Participants’ emotional evaluation of the AA consent artefact.

The participants’ evaluation (or appraisal) of the AA consent artefact makes them see it as something that is risky and irrelevant. The participants don’t perceive having control over the consequences of engaging with the consent artefact.

For example, some participants explained that they may be tense and worried when they come across a consent artefact because they cannot understand what they must do. The participants also report,

“[I]f [a person] does something wrong then that will increase his problems or this procedure will become more complicated. He will make a mistake and his loan might get cancelled… If he had the knowledge [about using the artefact] then he would fill this correctly and the process would be done easily. Since he did not have this knowledge, he thought it was better to leave it instead of making a mistake.”

Participants don’t perceive being able to cope with any such negative consequences arising out of the AA process.

- Making consent artefacts more effective

AA providers must design for these influences on a customers’ decision-making process when they design consent artefacts. The insights from the EthnoLabTM point towards an actionable design strategy that can help providers do this. This strategy builds on five decision levers that, when implemented, can improve customers’ engagement with consent artefacts (Figure 6)

The decision levers provide principle-level guidance to AA providers on how they design their consent artefacts. Our upcoming design toolkit supports these levers with more specific and actionable design elements. These elements are fine-tuned to counter the factors that make customers disengage from the consent journey at different stages of the consent journey i.e., from the point customers enter the AA interface to the point after they give consent.

Factoring in these design inputs can help providers improve how actively their customers engage with their consent artefacts. As a result, they can better align with the RBI’s standard for consent.

References

Gantayat, N., Ashok, A., Chugh, B., & Prasad, S. (2022, December 23). The behavioural mechanics that make notice-and-consent models ineffective. From Dvara Research: https://dvararesearch.com/2022/12/23/the-behavioural-mechanics-that-make-notice-and-consent-models-ineffective/

Reserve Bank of India. (2016). Master Direction – Non-Banking Financial Company – Account Aggregator (Reserve Bank) Directions, 2016. From Reserve Bank of India: https://rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_ViewMasDirections.aspx?id=10598

Reserve Bank of India. (2022). Guidelines on Digital Lending. From Reserve Bank of India: https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/GUIDELINESDIGITALLENDINGD5C35A71D8124A0E92AEB940A7D25BB3.PDF

[1] These elements are derived from the obligations concerning valid consent that the RBI’s Master Directions on NBFC-Account Aggregators, 2016 and the Guidelines on Digital Lending, 2022 impose on AAs and lenders, respectively.

Cite this blog:

APA

Gantayat, N., Ashok, A., Prasad, S., & Chugh, B. (2023). The factors making customers check out from the Account Aggregator journey . Retrieved from Dvara Research.

MLA

Gantayat, Nishan, et al. “The factors making customers check out from the Account Aggregator journey .” 2023. Dvara Research.

Chicago

Gantayat, Nishan, Anushka Ashok, Srikara Prasad, and Beni Chugh. 2023. “The factors making customers check out from the Account Aggregator journey .” Dvara Research.