The previous post covered the process of “Suitability” in financial services. Here, we cover aspects of the legal and regulatory structure that will aid in establishing an effective Suitability regime in India.

The primary objective of finance is to improve the financial well-being of consumers. For this to happen in India, there needs to be a shift towards a higher-trust-equilibrium between the consumers, financial service providers and the regulators. However, this is not possible to achieve under the following two scenarios:

- A disclosure-based approach to financial intermediation, which has inadvertently ended up as a way for providers to absolve themselves of their responsibilities to their consumers.

- A purely rule-based regime in which product approval is left in the hands of the regulator, absolves the provider of the responsibility of creating products that are truly welfare-enhancing for the consumer.

The “Suitability” regime seeks to reach this higher trust equilibrium by placing a direct responsibility, through legal liability, on the financial services provider for its advice or recommendation. To give teeth to this responsibility, it becomes a prerequisite to insert into law the Right to Suitability. The Approach paper recently put out by the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission seeks to enshrine this right in the law. Every citizen must have the right to be provided suitable advice or recommended suitable products. By incorporating this, consumers would be empowered to move a court of law in case this right is denied. Its introduction into primary law would be followed by changes to subordinated legislation which the regulators have the mandate to execute and supervise. This will shape the behavior of financial services providers, who will evolve the suitability process and practices that are consistent with subordinated legislation. The suitability regime places a very strong burden on everyday behaviour of the provider.The interpretation of suitability will emerge from the building up of case laws and judicial precedents, ensuring that our understanding of suitability comes from the reality and evolution of the market over time.

The Suitability regime would require the regulator to take a more non-interventionist approach towards product approvals for providers; providers should be free to develop products based on the needs of the market. This will ensure that both providers as well as regulators will have more leeway and will enable the creation of incentives that push the providers to innovate on socially useful product development. This does not however, in any way, indicate that the Suitability Regime would be a ‘light-touch’ one solely characterized by completely unrestrained market participants let loose on unsuspecting consumers. While the regulator steps back from product approvals, it would have greater supervisory responsibilities. This ex-ante regulatory oversight, coupled with a strong, unified ex-post redressal mechanism that also gives ‘real-time’ feedback to all regulators to aid in their monitoring, would provide severe disincentives for providers to offer bad advice or recommend inappropriate products to consumers. The redressal mechanism must include penalties that are not just compensatory in nature (to cover the losses incurred by the aggrieved), but also heavily punitive for non-compliance, which would act as a severe deterrent for the future. This could be in the form of direct liability on the heads of financial institutions, product recalls, and the like.

Coordination among regulators would assume tremendous importance in this regime. The Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC) plays a big role in facilitating this. The agenda for development of the financial sector must be decided solely by the FSDC and the Finance Ministry. Keeping the regulators responsible only for their respective domains will help remove any conflicting objectives the regulators might have faced otherwise.

How can suitability be enforced in a country like India where vast majority of the population have only limited or no access to basic financial services? If a consumer has access to only one product provider, should the provider sell the consumer a product that it has concluded to be unsuitable for her? Is Unsuitable access better or worse than no access? This situation, of a single product in low-access environments, can be overcome by getting the provider to develop natural suitability guidelines – which indicate a class of consumers for whom the product is automatically suitable; and serving the product to only those consumers. Besides, the provider can come up with natural “unsuitability” guidelines which, at the very least, stand by the principle of ‘do no harm’. This framework will automatically push for a bias in favour of distributors who can offer a single yet perfectly suitable product, and going forward, offer multiple products. It is likely that the Suitability equilibrium will shift the market from single product providers to multiple product providers.

The regulatory costs of implementing the Suitability paradigm need to be considered in greater detail. Further work will need to be carried out to arrive at a conclusion of whether the costs would be lesser or greater both in the short term and in the long term.

Also, greater thought will need to be given to develop a framework for supervising the Suitability regime. We can however learn from experiences from other countries which have already covered considerable ground in this aspect. The box below looks briefly at how Australia has been enforcing Suitability.

Enforcing Suitability – Lessons from Australia

Australia has a single market conduct regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), whose mandate is to ensure that Australia’s financial markets are fair and transparent, and are supported by confident and informed investors and consumers. ASIC administers the Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (FSR Act), which requires persons who provide financial product advice to retail consumers to comply with certain conduct and disclosure obligations. More details can be found here.

ASIC places legal obligations on financial services firms to meet specific conduct, disclosure, skills as well as professional indemnity insurance requirements, amongst others, to implement the Suitability requirement. Potential breaches of the law are brought to ASIC’s notice through reports of misconduct from the public, through referrals from other regulators, statutory reports from auditors and the licensees themselves, and through ASIC’s own monitoring and surveillance work (through regular surveillance visits and shadow shopping studies, the results of which are shared in the public domain). ASIC is empowered to take a variety of actions such as:

- Punitive actions such as court order, prison terms, criminal and civil financial penalties;

- Administrative actions (without going to court) such as ban on providing financial services, revocation, suspension or variation of conditions of licenses, public warning notices;

- Preservative actions such as injunctions; and

- Negotiated resolutions such as through enforceable undertakings, and others

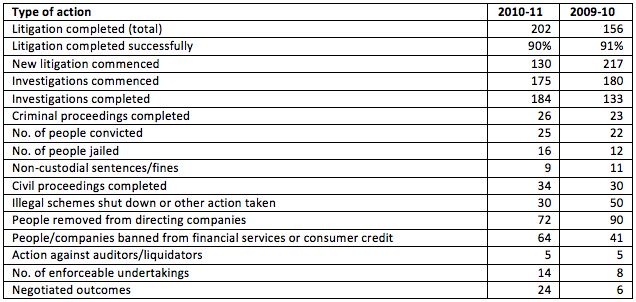

ASIC can decide on which remedy to take depending on various factors such as the severity of the suspected misconduct, the extent of losses, the compliance history of the individual or firm in question, and so on. The table lists major deterrence outcomes by type of action taken

(Source: ASIC Annual Reports):

6 Responses

Deepti: thank you for an excellent post. I feel that on the issue of legal costs one would have to examine more carefully the nature of signally that will take place. It is my sense that formal institutions respond very strongly to clear regulatory signals and modify their behaviours. The key challenge, as in the case of cheque bouncing, will be to suits filed consumers both serious and non-serious and how one develops a fast mechanism in the consumer courts to deal with them. How does Australia handle this — do they have separate courts that deal with these matters or does everything go back to the regular consumer courts?

Thanks Dr. Mor. Legally, Australian financial services providers are required to have in place a dispute resolution system that consists of:

i. Internal Dispute Resolution (IDR) procedures that meet the standards or requirementsmade or approved by ASIC; and

ii. Membership of one or more ASIC-approved External Dispute Resolution (EDR) schemes (through a fee).

A consumer must go through to the IDR scheme first, and if not satisfied with the

results, proceed to the EDR scheme. She can also approach the Federal court for redressal. While the IDR and EDR schemes are free of cost to the customer, redressal through courts would entail considerable financial burden on the customer. Providers are obligated to have in place IDR procedures and policies for receiving, investigating and responding to complaints within appropriate time limits; referring unresolved complaints to an EDR scheme; recording information about complaints; identifying and recording systemic issues; the types of remedies available for resolving complaints; and internal structures and reporting requirements for complaint handling.

The EDR responsibility is divided between three key organizations: The Financial

Ombudsman Service (FOS), the Credit Ombudsman Service (COS) and the Superannuation Complaints Tribunal (SCT). From 1 January 2010, EDR schemes operate on a compensation cap approach – a scheme has jurisdiction to hear a complaint or dispute involving more than the amount of the compensation cap, but is only able to award compensation up to the value of the compensation cap amount (upto $500,000, with caveats). Also, from very recently, ASIC has mandated EDR schemes to publish statistics about the number of complaints received and resolved against individual EDR scheme members (providers). The EDR mechanism is also an opportunity to improve industry standards of conduct and to improve relations between industry participants and consumers.

ASIC also approves codes of conduct developed by various industry bodies (a self-regulatory measure). In approving the code, ASIC takes into account the ability of the applicant (such as an industry body) to ensure that persons who agree to comply with the code actually do so. Enforceability of the code is through a contractual agreement by subscribers of the code to be bound by it. There is an independent body that is empowered to administer and enforce the code, including imposing any appropriate sanctions. The code provisions must also provide that consumers have access to IDR and EDR mechanisms for any code breaches resulting in direct financial loss, and there are provisions for complaining about any other breaches to the independent body.

Deepti,

Thanks for excellent post and the insights.

As justice delayed is justice denied what is the turn-around time that ASIC allows in terms of dispute resolution?

Thanks

Kgn

Thanks Sir.

When a customer comes with a complaint to the IDR, the provider is obligated to immediately acknowledge receipt of complaint/dispute

and proceed to address them.

– A final response (which is a written response to the complaint, setting out the final outcome offered at the IDR, and the right to complain to an EDR scheme, with its contact details) is to be given by the provider within 45 days (with some exceptions). For traditional services complaints, this timeframe is 90 days.

– Such a final response is not required if the compliant has been resolved to the customer’s complete satisfaction by 5 business days of receiving the complaint and if the customer hasn’t asked for a written response (with some exceptions).

– For some categories of complaints within credit services, there are shorter time frames, such as 21 days for disputes involving default notices. There are also specific timeframes for a lender to respond to a defaulted debtor’s application for contract variation on the grounds of hardship, and/or for postponement of enforcement proceedings.

If the complaint/dispute reaches the EDR (the FOS for instance here), the FOS makes a ‘Recommendation’ after taking time to investigate the issue. Both parties (provider and applicant) can accept this within 30 days, or proceed to ask the FOS for a ‘Determination’, which if accepted by the applicant within the next 30 days, would be binding on the provider. The applicant, if still not satisfied, can approach the courts. What’s more, the FOS may direct the provider to pay upto $3000 to cover legal and travel costs incurred by the applicant in the course of the dispute.

“The “Suitability” regime seeks to reach this higher trust equilibrium by placing a direct responsibility, through legal liability, on the financial services provider for its advice or recommendation.”

Does the Financial Services Provider provides advice/recommendation. As a layman if we compare insurance , there are brokers who advises and then there is an insurer.

Mr. Pattanayak, we argue that the very act of product or service delivery (be it as a recommendation or a direct sale) has embedded advice. Even when an agent (or broker) were to introduce himself as a representative of a particular manufacturer (the insurer in this case) and talks about his product, he is implying that the product is inherently good for the customer. The “Suitability” regime therefore intends to place a direct legal obligation on the provider and its representatives, for the suitability of its advice and sale.

Also, a separation of advice from distribution of financial products is fraught with problems in low-access environments where neither advice nor broking of products is available to the full extent, as is the case in most parts of India. The value of the financial service is unlocked at the point of delivery by how it can be customised to unique household needs, and therefore it may not be possible to identify products as being truly standard and free of the advice component.