Subsequent to our earlier post in the Consumer Protection series, this post covers conduct and disclosure obligations of Australian Financial Services (AFS) License holders for provision of advice to retail clients. While disclosure obligations have traditionally been driven by the principle of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), Australia provides an interesting case where a ‘suitability’ requirement (of the advice) is to be met by the provider and failure to do so is an offense.

The Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (FSR Act), which was incorporated into Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act 2001, requires persons who provide financial product advice to retail consumers to comply with certain conduct and disclosure obligations. These obligations were aimed at promoting consumer confidence and informed decision-making by the disclosure of all material information relating to the purchase decision in a manner that is easy to comprehend and promote product comparisons (including access to all such information).

The obligations vary depending on whether the advice given is personal advice or general advice. As per FSR Act, personal advice is financial product advice that is directed to a person (including by electronic means) in circumstances where:

(a) The provider of the advice has considered one or more of the person’s objectives, financial situation and needs

(b) A reasonable person might expect the provider to have considered one or more of those matters

All other financial product advice is general advice. All personal advice must meet the “suitability” rule while all general advice must be accompanied by a “general advice warning”.

Personal advice is considered to be ‘suitable’ if each of the following three elements is satisfied1 :

(a) The providing entity must make reasonable inquiries about the client’s relevant personal circumstances

(b) The providing entity must consider and investigate the subject matter of the advice as is reasonable in all the circumstances

(c) The advice must be ‘appropriate’ for the client

General advice warning2 requires the providing entity to warn the client that:

(a) The advice has been prepared without taking into account the client’s objectives, financial situation or needs

(b) The client should therefore consider the appropriateness of the advice, in the light of their own objectives, financial situation or needs, before acting on the advice

(c) If the advice relates to the acquisition of a particular financial product, the client should obtain a copy of, and consider, the PDS for that product before making any decision

The licensing regime introduced by the FSR Act, aimed to reduce compliance costs for businesses offering multiple products and services by having a single set of disclosure obligations. Disclosure requirements are three in number and need to be given in writing. These are:

Financial Services Guide (FSG)

The FSG aims to help the customer decide whether to avail a financial service. It is to be given to the customer as soon as it becomes apparent to the providing entity that a financial product or service is likely to be provided. It contains the following details:

• Name, contact and license details of the providing entity

• The kinds of financial services offered to customer

• Information about who the providing entity is acting for when providing the financial service

• Remuneration for the services being offered including details of commissions and other benefits

• Associations or relationships that might influence the providing entity in providing the service (conflicts disclosure)

• Details of the compensation arrangements required by law (such as professional indemnity insurance)

The information contained in the FSG must be worded and presented in a clear, concise and effective manner3 and must be up-to-date at the time it is given.

Statement of Advice (SOA)

The SOA is provided as soon as personal advice is provided to the customer and is aimed to help the customer decide on whether to act on the personal advice (including by checking whether the information captured about the customer is correct and whether in the providing entity’s opinion, the advice is appropriate). It contains the following details besides the details of the providing entity:

• A statement setting out the advice and an explanation of the basis on which it was given, including a warning if the advice is based on incomplete or inaccurate information

• Remuneration, commission and other benefits that the providing entity may receive in connection with the advice

• Any associations or relationships between the providing entity and product issuers (or anyone else) that could influence the provision of personal advice

Product Disclosure Statement (PDS)

The PDS is provided at or before the time of a recommendation being made to buy a financial product or when an offer is made for the issue of a financial product. It is aimed to help the customer in deciding whether to purchase the product or service. The PDS contains the following details:

• Fees payable, commissions, other benefits, if any, to be disclosed in dollar4 terms

• Risks and benefits of the product

• Significant characteristics

• Significant tax implications

• Dispute resolution procedures

• Cooling off rights, if any

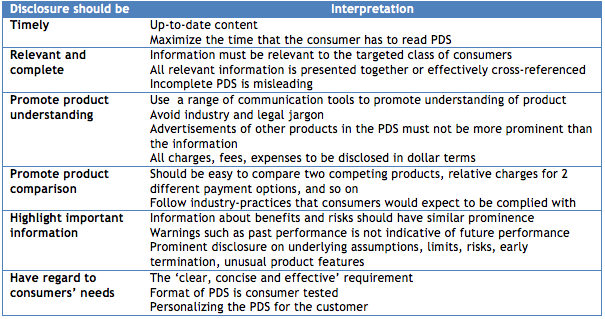

While ASIC does not vet any PDS prior to its release, it lays down ‘good disclosure principles’5 to help product issuers, advisors and those producing promotional publications to comply with the disclosure requirements and promote good disclosure outcomes for consumers. The table below lists these and a few examples of how ASIC interprets them.

The 2005 amendments to the Corporations Act 2001 introduced major changes to the above obligations for product issuers and licensees. Some of these include:

• Allowing licensees to tailor their FSGs according to the customer’s specific information needs

• Removing/reducing certain information from the FSG which would get covered in the PDS or in the SOA

• Exempting from the obligation to provide an SOA while giving further advice to an existing customer, subject to certain conditions

• Allowing issuers of financial products to provide a short-form PDS containing core information about the product, with full information available on request or easily available, such as in the internet

• Exempting PDSs for simple products such as for basic deposit products (issued by an authorised deposit-taking institution or ADI), or a related non-cash facility or traveller’s cheques

The major criticism to Australia’s disclosure obligation for financial service providers has been that the resulting documents have been difficult to comprehend and depend on the financial literacy levels of the individual consumer. Since the length is not prescribed, they are often very long, up to 50-100 pages, and contain legal and technical jargon. This stems from the tendency to include detailed information to avoid potential liability for omissions. The format for the document has been left to the providing entities, making it difficult for consumers to compare products. To achieve the objective of comparability between products as envisaged by the Wallis report, regulatory reform may need to prescribe either the form or the length of these disclosure documents. Consumer testing and extensive consultation with industry and consumer bodies would be needed to arrive at what would be optimal.

—

– s945A, Corporations Act 2001

– s949A, Corporations Act 2001

– s942B(6A), Corporations Act 2001

– Regulatory Guide 182, ASIC

– Regulatory Guide 168, ASIC

2 Responses

This is a great post Deepti. One of the issues I am unclear about is that if the suitability regime exists, what is the role for disclosure? Suitability tests effectively place the onus on the provider whereas disclosure follows the “buyer beware” approach. Why have both?

Thanks Bindu. Disclosures serve the purpose of

reducing information asymmetries. Two things may be kept in mind while

considering disclosure versus suitability: one, that there is an advice

component implicit in almost all financial product/service sale, and two, that

information asymmetries will continue to exist and perhaps widen further with

greater market innovation. Consequently, imbalances in information, expertise

and power between the buyer (customer) and the seller (advisor) are bound to

increase, requiring that the onus of consumer protection be placed on the seller

to ensure good outcomes for the buyer. However, in the absence of a pure

advisor regime, the advisor is also a broker, receiving commissions in some

form or the other. Though it can be argued that disclosing conflicts of

interest by the advisor (such as details about commissions) could be of no

greater use to the customer in taking a financial decision (or could even

worsen the situation, by placing the onus on the customer to skim the market

for better or cheaper alternatives), customers have the right to be informed

about product features.

Australia’s

next generation Future of Financial Advice (FOFA) reforms are slated to be a step towards strengthening ‘suitability’ requirements.

Besides proposing to ban all conflicted remunerations such as commissions and

volume-based payments, FOFA is introducing a statutory fiduciary duty on

financial advisors to act in the best interests of their customers and to place

the interests of their customers ahead of their own when providing personal

advice. Ultimately, it is the customer who decides whether to trust the

provider, and these tools help channel conduct towards better outcomes for the

customer and the alignment of these outcomes with the

provider’s incentives.