In the previous blogpost we noted the gradual shift away from the buyer-beware standard in case law and policy regarding customers of financial products. So far this move towards more provider liability has occurred in a piecemeal fashion – through decisions of the courts and regulations of certain regulators. For the first time in Indian law, the draft Indian Financial Code (IFC) is proposing a statutory obligation of this kind when it comes to retail financial services. Providers offering products and services in the course of day-to-day retail financial services business (such as discussing a loan with a borrower) will have to begin undertaking an “assessment of suitability”.1

Separately, the RBI’s Charter of Customer Rights has enunciated five customer rights including the “right to suitability” i.e. the right for customers to be offered products appropriate to their needs. The RBI has advised banks to formulate a board-approved policy incorporating these rights into their business process, along with monitoring and oversight mechanisms for ensuring adherence.2

As the movement towards more provider-liability grows, we pause to ask:

Could requiring higher standards of conduct from retail financial advisors fundamentally shift the legal duty of care we expect from them? Will these change the standards of civil liability in tort law that retail financial services providers are subject to?

Wider civil law liability under tort law operates over and above contractually-agreed terms and conditions between financial services providers and customers. This question is important because it could subject financial services providers to a higher legal standard of care irrespective of the contractual terms of their products.

Could we foresee a future where Indian tort law begins to recognize a higher standard of care for financial services providers?

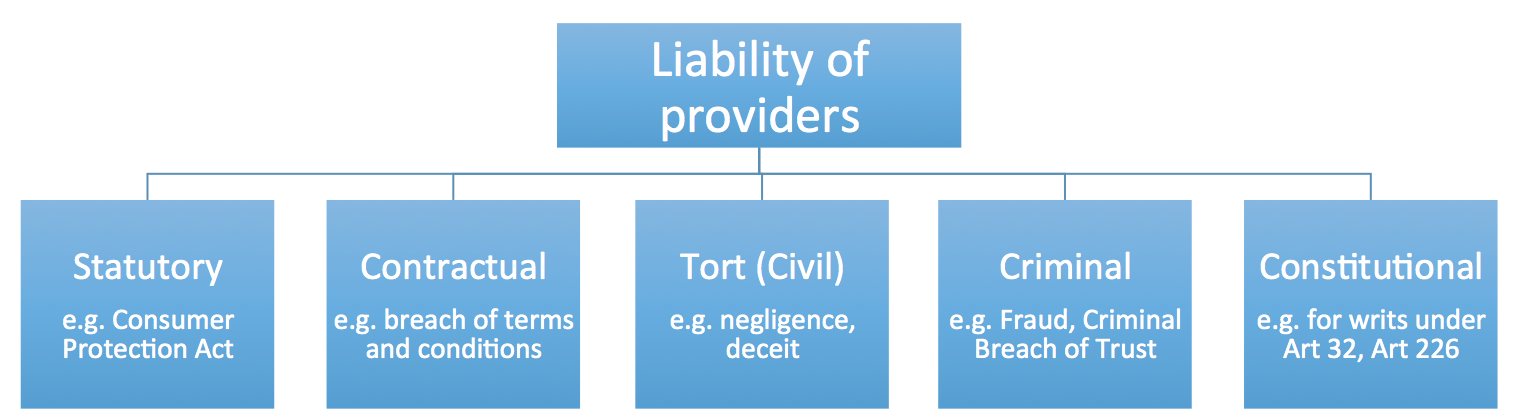

Currently, customers of products can raise claims against faulty products or poor service through a range of legal avenues. These avenues can arise from:

- Written legislation or statutes which give customers rights (like the Sale of Goods Act, or the Consumer Protection Act),

- The specific contract between the provider and the customer (in the case of financial products, the product’s terms and conditions),

- Civil liability under tort law where a “tort” or civil wrong arises from a breach of duty (independent of any contractual breach) for which an action for compensation can be pursued,

- Through criminal law (for e.g. financial crimes like fraud or criminal breach of trust),

- And finally, by approaching courts when customers feel that fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution have been infringed (especially in cases involving public financial institutions).

Tort law – a branch of civil liability that has evolved from judge-made common law – has continued its development in Indian courts. Of specific relevance to our current discussions, is the tort of negligence which deals with loss or harm caused by the careless or unreasonable conduct by a person to another. For an act or omission to constitute the tort of negligence, there must have been (i) a legal duty of care that one party owed to another party (ii) a breach of this duty (iii) which results in the other party to suffer loss or damage as a result.3

To understand the duty of care that is owed by the allegedly negligent party in any situation, the standard applied is of the “reasonable person” i.e. whether a reasonable person in the same situation would have acted differently. This objective standard is raised for people performing actions which require special skills, such as doctors, lawyers, financial advisors or accountants. These types of service providers have their actions or omissions compared to a reasonable skilled person within their discipline, rather than the average person on the street.

It is foreseeable that the regulations implementing suitability requirements under the draft IFC will require specific training for providers’ staff to help them assess suitability of products. This is the case in the UK, for example, where the regulator expects firms to have internal systems to manage suitability requirements, including training customer-facing staff to understand the boundaries between advisory and other services, and undertake suitability assessments.4 The draft IFC appears to be moving towards engendering a process-oriented approach for assessing suitability by providers. The Indian Banks’ Association’s Model Customer Rights Policy, formulated at the RBI’s behest, also makes several references to appropriate training of staff. As we know anecdotally, retail advisors already hold weight when recommending products and services to customers. Requirements for advisors to undertake training could add to the manner in which they are perceived to be people of higher knowledge and skill, and raise the duty of care when they interact with customers. This is especially given that in the IFC, “advice” is defined widely to cover any communication directed at the consumer which could influence the consumer’s transactional decision making.5 Any higher duty of care for staff of providers would obviously not apply to non-advisory tasks which don’t require an exercise of discretion (like basic bank teller functions).

It’s important to note that moving towards a higher standard of care for the staff of providers would not make them the scape-goat for all financial losses customers suffer. If market forces affect the returns from products, providers can’t be held responsible for this. As a parallel, we do not hold doctors liable if the patients’ body rejects a kidney. However, the law does expect the doctor to have used the same diligence in the treatment and operation as another doctor of the same skill would have.

Likewise, if customers provide false information then providers can’t be held liable for improper advice. Under tort law, the doctrine of unclean hands would give providers a defence against customers who act in bad faith. Additionally, contributory negligence is a principle in tort law that would protect providers where customers through their own actions contributed to the harm they suffered. The draft IFC also absolves providers of responsibility in the case of information about customers’ personal circumstances which was not obtainable despite “exercise of professional diligence”.6

In conclusion, the question of whether retail financial services providers providing advice and recommendations to retail customers should implicitly owe a higher standard of care to customers is one that beckons tantalizingly in Indian tort law. It will be interesting to see if the general trend towards provider-liability for financial services will reimagine deeper civil liability standards for providers in India. Such a development could be one more piece in the armour of customer protection law in India.

This is the concluding post of the series which you can access in full here.

—

- Section 120(1) of the draft Indian Financial Code, draft released 23 July 2015, Available at < http://finmin.nic.in/suggestion_comments/Comments%20on%20Draft%20IFC.asp> (Accessed 15 January 2016) (Hereafter the “draft IFC”).

- https://dvararesearch.com/2014/12/04/suitability-becomes-a-customer-right/

- For an accessible text (available free at the time of writing online) see Part III (The Tort of Negligence) of Jenny Steele, Tort Law: Text, Cases and Materials (3rd edition 2014, Oxford University Press) Available here. (Accessed 15 January 2016).

- Practical Law, FCA Suitability requirements: COBS 9, Available here. (Accessed 15 January 2016).

- Section 2(6) of the draft IFC.

- Section 120(2) of the draft IFC.