The current regulatory approach to customer protection in India can be divided into two complementary ex-ante approaches- mandated information disclosure, and financial literacy and education. Both approaches, predicated on the principle of ‘buyer beware’, seek to improve the decision-making ability of the consumer by reducing the information asymmetry between the buyer and the seller. However, recent studies find that these approaches do not adequately protect the customer. For example, customers are often ‘over-loaded’ with information by disclosure documents and this leads them to take sub-optimal decisions1. Evidence also suggests that firms do not use these measures to act in the best interest of the customer. For example, in the Indian mutual fund context, studies have shown that firms respond to disclosure policy relating to un-shrouding of fees by altering products to essentially maintain lack of clarity in pricing2. Evidence also points to the weak relationship between financial literacy and financial behaviour. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 168 papers that study the relationship between financial literacy and financial behaviour finds that interventions to improve financial literacy explain only 0.1 per cent of the variance in financial behaviours studied, with weaker effects in low-income samples3. When the fact is considered that asymmetry in information, expertise, and power between the buyer and seller of financial products will only be exacerbated in the future, it becomes clear that existing approaches cannot underpin the customer protection regime in India.

The report of the Committee on Comprehensive Financial Services (CCFS) argues that India needs to move to a customer protection regime where providers need to be held accountable for the service to the buyer. Taking the lead from the FSLRC, the CCFS Report envisions that each low-income household and small-business would have a legally protected right to be offered only suitable financial services. The Committee recommends that the RBI should issue regulations on Suitability, applicable specifically for individuals and small businesses, to all regulated entities within its purview. These regulations should be applicable specifically for individuals and small businesses defined under the term ‘retail customer’ by the FSLRC4.

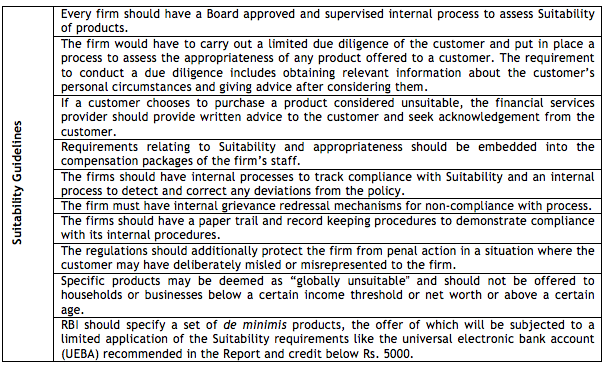

As described in the table above, the notion of Suitability should be viewed as a process followed by the provider rather than as a guaranteed outcome for the customer. Suitability as a process requires every financial services provider to have a Board approved Suitability Policy that the company must follow in all interactions with customers and it will be the implementation of the Suitability process that will determine if a financial services provider has indeed acted in the best interests of the customer. Global financial customer protection regimes in Australia, UK, and USA have shifted to a provider-liability regime and mandated a process for ensuring Suitability. For example, in the case of a standard home loan product, regulators in these countries require that Suitability assessment take into account three parameters:

a. Customer’s requirements and objectives: The Australian Suitability assessment mandates that the financial services provider look into several aspects of the customer’s requirements and objectives including the purpose for which the credit or customer lease is sought, the nature of the credit requested by the customer, and the customer’s understanding of the proposed contract.

b. Financial Situation of the customer: CFPB regulations in the USA require that monthly payments be calculated based on the highest payment that will apply in the first five years of the loan and that the customer have a total debt-to-income ratio that is less than or equal to 43 per cent.

c. Other parameters: Certain regulations like the US guidelines deem specific characteristics of a home loan product (like loans with negative amortisation, interest-only payments, balloon payments, terms exceeding 30 years and the so-called no-doc loans) to be “globally unsuitable” for all categories of customers.

Suitability is by no means a new concept in India. For example, the RBI itself has issued Suitability and Appropriateness guidelines for derivative products. These guidelines mandate that market-makers should undertake derivative transactions, particularly with users with a sense of responsibility and circumspection that would avoid, among other things, mis-selling. SEBI’s Investment Advisers Regulations, 2013 mandate that the investment advice provided should be appropriate to the risk profile of the client and that the structure and risk reward profile of the recommended product should be consistent with client’s experience, knowledge, investment objectives, risk appetite and capacity for absorbing loss.

The CCFS also endorses the creation of a unified Financial Redress Agency (FRA) as a unified agency for customer grievance redress across all financial products and services. This Agency is envisaged to be consumer facing and will in turn coordinate with the respective regulator for customer redress. This way, the consumer will not be expected to understand regulatory architecture to lodge a grievance.

Furthermore, the report recommends a citizen-led approach to surveillance and monitoring. The report provides the example of the Economic Offenses Wing (EOW) of the Tamil Nadu Police Department which has engaged members of the public to monitor non-banking financial institutions in the state. Taking a lead from this, the Committee recommends that RBI should create a system by which any customer can effortlessly check whether a financial firm is registered with or regulated by RBI. Customers should be able to access this service by phone, through SMS or on the internet.

—

- See: Spindler, Gerald. “Behavioural Finance and Investor Protection Regulations.” Journal of Consumer Policy 34, no. 3 (2011): 315-336.

- See: Anagol, Santosh, and Hugh Hoikwang Kim. 2012. “The Impact of Shrouded Fees: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in the Indian Mutual Funds Market.” American Economic Review, 102(1): 576-93

- See: Fernandes, Daniel, John G. Lynch, and Richard G. Netemeyer. “Financial Literacy, Financial Education and Downstream Financial Behaviors.” Management Science (2013).

- FSLRC defines a retail customer as “an individual or an eligible enterprise, if the value of the financial product or service does not exceed the limit specified by the regulator in relation to that product or service.” Further, an eligible enterprise is defined as “an enterprise that has less than a specified level of net asset value or has less than a specified level of turnover.”